[2]

[2]

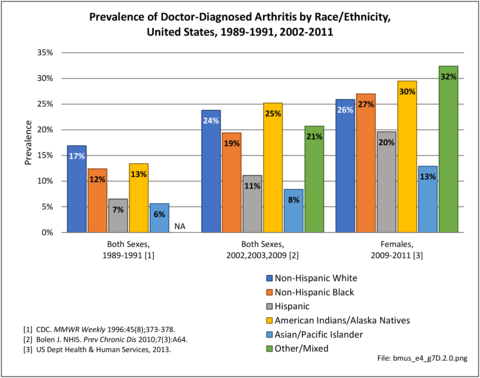

Research starting in the late 1980s and extending to 2011 shows a consistent pattern of doctor-diagnosed arthritis prevalence among races and ethnicities, although prevalence rose among all groups. Persons of Hispanic ethnicity and Asian/Pacific Islanders have lower arthritis prevalence than non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and non-Hispanics of other races. However, a study of the 2013 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) participants residing in Hawaii of health disparities of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI), Whites, and Asians found that NHPI males had a significantly higher prevalence of arthritis, which peaked twenty years earlier, than White and Asian males. The prevalence of arthritis peaked at 65-79 years in males and females in all racial groups, except NHPI males where it peaked at 45-54 years. At the NHPI peak age range, arthritis prevalence was 49.4% among NHPI males compared to White males (222.2%) and Asian males (17.9%). No significant differences were found among females.1

American Indians/Alaska Natives higher than non-Hispanic blacks and resembling non-Hispanic whites.2,3 A 2009-2011 study of prevalence rates among females only reported the same pattern, but with higher rates than found in both sexes.4 Arthritis-attributable activity limitation, arthritis-attributable work limitation, and severe joint pain were found to be higher for non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and multiracial or other respondents with arthritis compared with non-Hispanic whites with arthritis.3

Osteoarthritis, or degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis. The incidence of osteoarthritis in different ethnicities is similar. Disabling OA is at least as prevalent among African Americans and Hispanics as among non-Hispanic whites.5 African-Americans, however, report greater pain and activity limitation in comparison to Caucasians.6,7,8 African-Americans have higher prevalence of knee symptoms, radiographic knee osteoarthritis, and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis than whites,8 and 77% more likely to have knee and spine osteoarthritis together.9 Hispanics are 50% more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to report needing assistance with at least one instrumental activity of daily living and report difficulty walking.10 Prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee is on the rise, due in part to the growing epidemic of obesity. Hispanic and African-American women have disproportionatly high rates of obesity leading to higher rates of knee osteoporosis, with subsequent quality-adjusted life-years losses, than found among Caucasian women.11

There is evidence of race-based differences in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Ethnic variations have been found in the clinical expression of RA, both in the frequency and types of SE-carrying HLA–DRB1 alleles,12 with non-Hispanic whites having the lowest percentage of rheumatoid factor positive results.13 Hispanics exhibit more tender and swollen joints than non-Hispanic whites, while African-Americans are slightly older at onset.12 African American and Hispanic patients have higher disease activity level, lower rates of remission, and worse functional status than white patients, in spite of more aggressive treatment strategies in recent years.13,14 There are also differences in utilization of disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs (DMARDs), the gold standard treatment of RA. Certain studies suggest that treatment differences may be related to patient preference. Constantinescu et al found that fewer African-American patients preferred aggressive treatment compared to white patients with similar disease severity.15 This study suggests that improvement in patient literacy about rheumatoid arthritis could decrease the disparity in management.

Gout, one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis, is characterized by severe joint pain and destruction. A population-based cohort study demonstrated that African-Americans were at an increased risk of gout.16 African-Americans with gout have also been found to function worse than their Caucasian counterparts.17 Another database study found that African-Americans with gout were less likely to receive urate-lowering therapy with allopurinol.18 Studies have shown a similar efficacy of ULT between black and white patients.19,20 These results suggest that decreasing the disparity in gout treatment will improve disease severity in African-Americans.

Ethnic disparity has been widely studied in SLE, with findings that West-African immigrants experience SLE (lupus) more than those native to Europe or America, with many having the condition before migration. A San Francisco study found SLE was four times higher in African-American women than in Caucasian women. Among Asians, SLE is reported to be more frequent among Chinese settling outside China.21

Total hip and knee replacements, generally indicated for end-stage arthritis, are two of the most common and successful major surgical procedures performed in the United States. Outcomes after total joint replacement are similar between black and white patients after controlling for socioeconomic factors.22 Unfortunately, racial disparities in the utilization of these procedures has been demonstrated in multiple studies. A Medicare database study by Singh et al demonstrated that blacks are less likely to receive joint replacement surgery compared to whites. Importantly, the utilization disparity did not improve over an 18-year period. Blacks also had inferior outcomes including longer hospital stays and higher rates of readmission.23 Another prospective study revealed that blacks are less likely to receive a recommendation for joint replacement surgery; however, this difference appeared to be related to patient treatment preference.24 African American patients are also less familiar with TKA than their white counterparts and more likely to anticipate greater perioperative pain and longer recovery.25,26 Thus, patient education about the procedure is likely a major factor that will increase utilization of joint replacement procedures by African-Americans.

In 2015, non-Hispanic whites and Non-Hispanic blacks self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis (told be a doctor they have arthritis) at similar rates (22.6/100 persons and 22.2/100, respectively), while persons of Hispanic ethnicity reported a lower rate (15.4/100). Persons of non-Hispanic other/mixed race did not report in sufficient numbers to be cited. (Reference Table 7D.4.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

The numbers reported for arthritis-attributable activity limitations as a total followed the same pattern as doctor-diagnosed arthritis, with non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks similar (11.1/100, 10.9/100, respectively), Hispanics much lower (5.7/100), and insufficient numbers of non-Hispanic others/mixed race to be cited. However, by specific type of limitation, non-Hispanic blacks report higher rates than other racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 7D.4.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

In 2015, those of Hispanic ethnicity reported more lost work days due to arthritis, on average, than other racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 7D.4.2 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Considering only hospitalizations with an arthritis diagnosis, in 2013, non-Hispanic blacks had a slightly higher rate (2.8/100 persons) than non-Hispanic whites or Hispanics (2.6/100), with non-Hispanic others/mixed race much lower (1.1/100). The HCUP NEDS (emergency department) database does not report race/ethnicity, hence no numbers are available for other types of healthcare visits. Non-Hispanic blacks also had slightly longer hospital stays with an arthritis diagnosis. (Reference Table 7D.4.2 PDF [11] CSV [12])

Joint replacement is a common procedure performed to alleviate the pain from arthritis. As noted above, the literature reports lower rates of hip and knee procedures among non-Hispanic blacks. This finding is supported by the rates of all arthroplasty procedures performed in hospitals in 2013. Non-Hispanic white persons received 80% of hip replacements and 77% of knee replacements compared to the 62% of the population they represented. All other racial/ethnic groups had small shares of procedures than they represented in the population. (Reference Table 7D.4.3 PDF [19] CSV [20])

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d20png

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.0.png

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.1.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.1.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d21png

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.1.png

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d221png

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.2.1.png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d222png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.2.2.png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.2.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.2.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d25png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.5.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d23png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.3.png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d24png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.4.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.3.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_t7d.4.3.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g7d26png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g7d.2.6.png

[23] https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041424.htm

[24] http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/may/10_0035.htm

[25] http://healthfinder. gov/news/newsstorv.aspx?Docid=658088