Special populations looks at sex and gender, as well as age, as mitigating factors in the presentation of musculoskeletal diseases.

In addition, the special needs of active and inactive military personnel are examined.

The term “women’s health” has historically referred to conditions affecting the reproductive organs. It was assumed that there were minimal differences between men and women in conditions related to other organ systems. However, expanding research in women’s health over the past several decades has identified major differences in etiology, incidence, presentation, prevention, and response to treatment for almost all health conditions. These differences are impacted by both sex and gender, and are particularly manifest in the musculoskeletal system. Thus differences and similarities in musculoskeletal health related to sex and gender are inadequately covered in the term "women's health."

Inadequate research of health conditions in women contributed to limitations in this area. In 1977, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) barred women of childbearing potential from participating in most early-phase clinical research. In 1985, the Public Health Service Task Force on Women's Health Issues noted that the exclusion of women as subjects in clinical research was detrimental to women’s health. In 1986, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) urged that more women be included in clinical investigations where appropriate, and in 1990 established the Office of Research on Women’s Health. The FDA reversed its 1977 edict, excluded women from clinical trials in 1993, and in 1998, stated they would refuse to file any new drug application that did not include a sufficient number of female subjects to assess safety and efficacy by sex.

Despite this new direction, there are concerns that sufficient numbers of women still are not being included in studies. This is particularly true for pharmaceutical trials, where recent research has shown differences in effect and assimilation of drugs between men and women, resulting in questions related to the safety and efficacy of medications used to treat conditions in both sexes. Recent recommendations for differing doses between the sexes for some medications have highlighted these sex differences.

The current focus is a movement away from terms such as “women’s health” to a more inclusive discussion of sex and gender differences. The words “sex” and “gender,” although frequently use interchangably, have differing meanings. The Institute of Medicine attempted to clarify the difference in their 2001 publication, noting that sex reflects the genetic, or gonadal, complement and that “every cell has a sex,” while gender refers to social interactions and the ability to access resources. Both sex and gender have an impact on health conditions, including those of the musculoskeletal system.

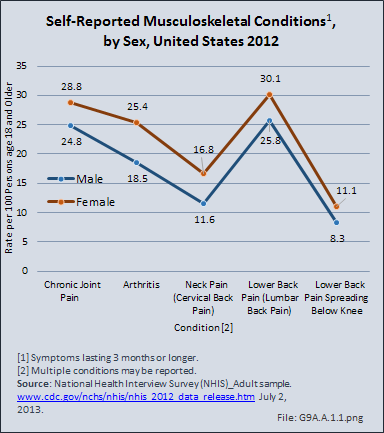

Women self-report slightly higher rates of musculoskeletal conditions, joint pain, limitations in activities of daily living, bed days, and lost workdays due to musculoskeletal conditions than men do. The etiology of the differences noted between women in men in these conditions is multifactorial and is not solely or consistently attributable to differences in sex hormones.

Women report musculoskeletal and chronic joint pain at slightly higher rates than men do. The greatest difference is in self-reported rates for arthritis, with more than 25 women in 100 over the age of 18 years reporting they have arthritis, compared to 19 men. However, more than half of both men (51%) and women (56%) report they have musculoskeletal pain, in either the back, neck, or joints. (Reference Table 9A.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

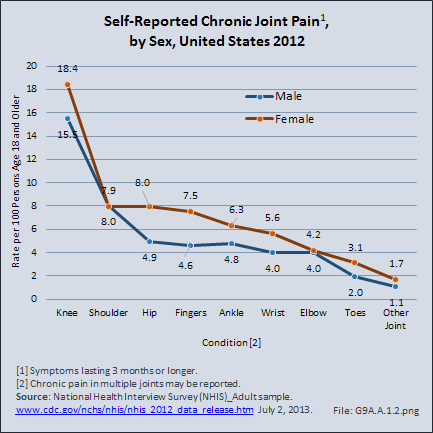

The knee is the most common joint with chronic pain reported by both men and women, followed by the shoulder. Women are much more likely than men to complain of issues related to their patellofemoral joint and to present with anterior knee pain syndrome. Several etiologies have been suggested for this, including sex-based differences in anatomic alignment, such as larger Q-angle; tendency toward foot pronation; increased femoral anteversion, genu valgum, external tibial torsion, and tibia vara; as well as a variety of other anatomic differences such as patella alta, shallower femoral notch, narrower patellae, patellar ligamentous hypermobility, insufficient VMO versus vastus lateralis, generalized ligamentous laxity, tight lateral patellar retinaculum, and tighter IT band.

Shoulder and elbow joint pain is reported at similar rates by men and women. For all other joints, women are slightly more likely to report chronic joint pain. (Reference Table 9A.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

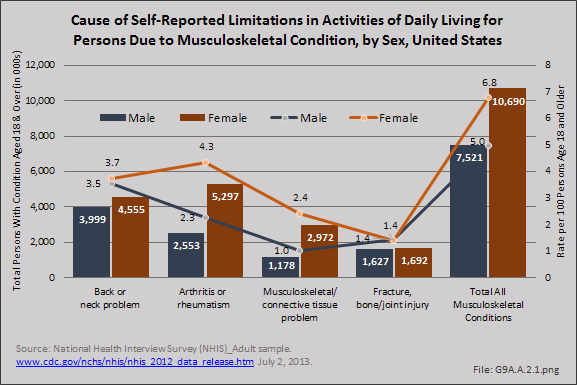

Women also report they experience limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) in higher rates for musculoskeletal conditions, with the exception of fractures or bone/joint injuries, than men do. Again, arthritis is identified as the most common cause of ADL limitations due to musculoskeletal conditions. In 2012, nearly 10.7 million women reported ADL due to musculoskeletal conditions, while 7.5 million men did so. (Reference Table 9A.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

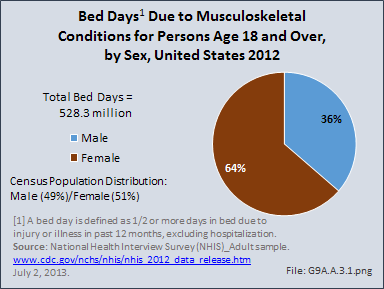

Women account for nearly two-thirds (64%) of the 528.3 million bed days reported in 2012 due to a musculoskeletal condition. A bed day is defined as one-half or more days in bed due injury or illness, excluding hospitalization. The greater number of total bed days reported by women is due to both a higher number with musculoskeletal-caused bed days, and a higher mean number of days in bed (9.9 days versus 8.2 days for men).

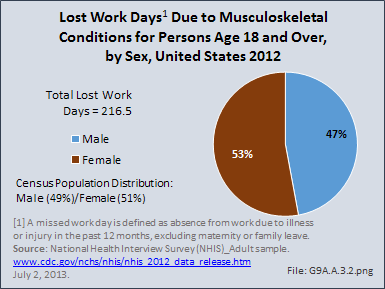

Women also account for slightly more than half (53%) of the 216.5 million lost work days due to musculoskeletal conditions, because of the greater number of women reporting lost work days (15.4 million versus 12.7 million men). However, men reported a mean of 8.0 lost workdays due to musculoskeletal conditions, while women reported a mean of 7.5 days. (Reference Table 9A.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Sex-based differences in incidence and presentation have been described for some, but not all, conditions of the spine. For example, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, one of the most common diseases of the spine in adolescence, is somewhat more common in females, and females are much more likely to present with larger curves. The incidence of scoliosis among adults, which includes a wider range of diagnoses than adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, does not appear to differ by sex, and there appears to be no sex-based differences in magnitude of curves.1 Ankylosing spondylitis is diagnosed more frequently in men. However, women who present with this condition tend to be older than their male counterparts, have a shorter duration of disease, be more likely to have thoracic spine involvement, and be less likely to be HLA-B27 positive.2

Among the common conditions of the spine, data are often conflicting regarding any sex-based differences in incidence, most likely reflecting their multifactorial etiology. Degenerative disc disease and lumbar radiculopathy, for example, have been reported to be more common in men, more common in women, or equal in lifetime sex-based risk. Women with degenerative disc disease have been noted to present with this condition when they are approximately 10 years older than men,3 perhaps reflecting differences in activity and mechanical loading. Among a young active military population, degenerative disc disease4 and lumbar radiculopathy5 were found to be more common among women, although female sex was less of a risk factor than older age for both conditions.

A variety of risk factors have been described to account for any noted sex-based differences among spine conditions. The most obvious difference would be the influence of sex hormones. Studies related to hormones and spinal deformity, which is more common in women, have shown no clear relationship, while in cases of ankylosing spondylitis, which is more common in men, studies have shown no differences in adrenal or gonadal sex hormones6 to explain this predominance.

As with other conditions, any sex-based differences are likely multifactorial. Schoenfeld5 postulated that these differences might reflect hormonal influences as well as differing responses of the spine to loading and physical activity. Among a cohort of asymptomatic young adults,7 it was found that the spine from T1-L5/S1 as a whole, and the individual high thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, were more dorsally inclined in women than in men. The authors hypothesized that this could make the spine less rotationally stable in women, in certain circumstances resulting in the initiation and/or progression of spinal conditions, such as scoliosis.

The potential impact of sex on other spine conditions has also been studied, without conclusive results. Increased paraspinous muscle degeneration has been suggested to correlate with incidence of low back pain,8,9 and in studying a cohort of symptomatic adult patients, it was found that women were more likely than men to demonstrate fatty infiltration of their paraspinous muscles on MRI. Sex-based differences have also been identified in paraspinous muscle fiber and type.10 However, the impact of sex on the development of low back pain. and any cause-and-effect relationship between low back pain or other spine conditions and changes in paraspinous muscle composition, has not been elucidated.

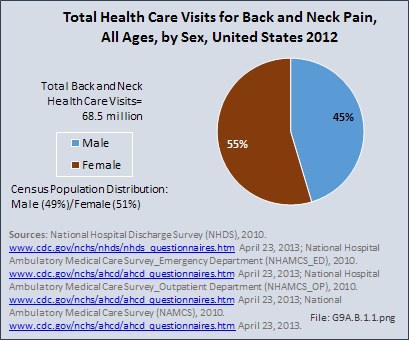

Women accounted for 55% of the 68.5 million total health care visits for back or neck pain in 2010, slightly more than the 51% of the population they represent. Total health care visits include hospital discharges, ED and outpatient clinic visits, and physician office visits. (Reference Table 9A.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

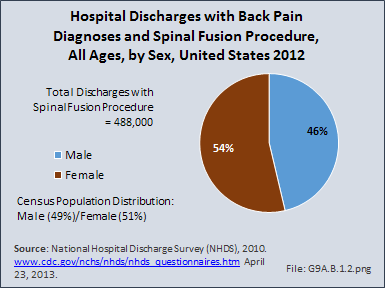

Women also accounted for 54% of 488,000 hospital discharges for back pain that involved a spinal fusion procedure. (Reference Table 9A.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

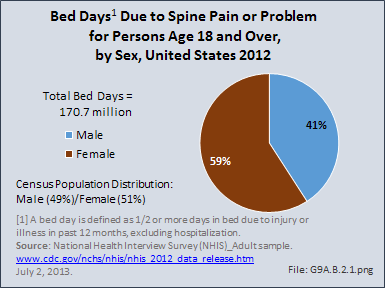

Women reported taking bed days for back and neck pain in higher numbers than men do. They also reported an average bed stay of about one-half day longer, 7.8 days in the previous 12 months, compared to a mean of 7.4 days for men. Overall, women accounted for 58% of total bed days in a previous 12-month period. (Reference Table 9A.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

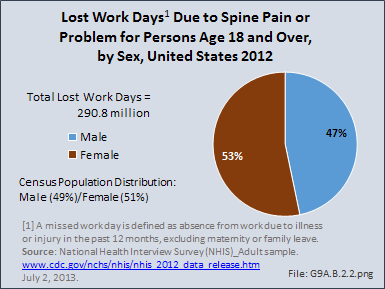

Men, however, report losing more workdays in a 12-month period than women do, accounting for 59% of lost workdays reported in 2012. Although slightly fewer numbers of men reported lost workdays than did women, they lost an average of one day of work more than women did, 11.9 days versus11.0 days lost. (Reference Table 9A.2 PDF [3] CSV [4])

Women are more likely to demonstrate scoliosis, especially adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, than are men. Although a variety of explanations have been presented to account for this, no single sex-based risk factor has been identified. However, females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis tend to present with larger curves, and the potential role of estrogen in the development and progression of this condition, especially considering the impact of estrogen on bone metabolism and development,1 has been extensively studied. Still, no clear-cut influence on the onset or progression of idiopathic scoliosis has been identified. Older age at the onset of menarche has been found to be associated with an increased likelihood of presenting with a more significant curve among patients with adolescent scoliosis. However, specific estrogen polymorphisms have not been consistently correlated with age at menarche or curve severity.2

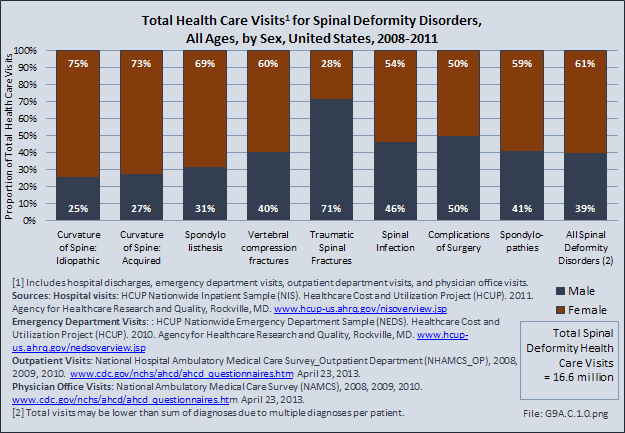

Although women represent 51% of the total population, they have a greater than expected rate of health care visits for the majority of spinal deformity disorders. This is particularly true for both idiopathic (75%) and acquired spinal curvature (73%), and for spondylolisthesis (69%), a spinal condition that causes one of the lower vertebra to slip forward onto the bone directly beneath it. Traumatic spinal fractures occur at a greater extent to men, while vertebral compression fractures, often due to osteoporosis, occur much more frequently in women. Spinal infections and complications from surgery related to spinal deformity occur about equally between men and women.

Spondylopathies, which refer to any disease of the vertebrae associated with compression of peripheral nerve roots and spinal cord, causing pain and stiffness, were diagnosed more frequently (59%) in health care visits by women than by men (41%).

Overall, on an annual average, 16.6 million health care visits for spinal deformity conditions were made each year in the years 2008 to 2011. Of these visits, 61% of those treated were women. (Reference Table 9A.3 PDF [5] CSV [6])

Arthritis is a condition impacted by both sex and gender. Women are more likely to present with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis than are men as reflected by both self-report and radiographic studies. Specific joints appear to be at particular risk of sex-based disparities in incidence. Sodha noted in a study of hand radiographs that, after the age of 40 years, women were significantly more likely than men to have incidentally noted radiographic osteoarthritis of the hand, especially the first carpometacarpal joint.1 This incidence increased with age, especially for women, with more than 90% of women over the age of 80 years having this finding.

The increased risk of inflammatory arthritis likely reflects the overall higher rate of inflammatory conditions found in all organ systems among women. This may reflect an impact of sex hormones, especially alterations in estrogen levels, as estrogen has been found to impact B and T cell homeostasis, as well as to impact interferon regulation.2 A variety of etiologies have also been proposed, but contradictions remain in the available evidence.

The etiology of the higher rate of osteoarthritis among women also is still under debate and appears to be multifactorial. There is some indication that osteoarthritis in women has a different course than seen in men. Maillefert 3 followed 508 patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and noted that women are more likely to have polyarticular disease (pain in multiple joints), superolateral migration of femoral head, more severe symptoms, and more rapid loss of joint space. Some conditions that may increase the risk of osteoarthritis are more common, or differ in presentation in women. For example, the rates of acetabular dysplasia and pincer-type femoroacetabular impingment are higher in women. Potential explanations for differences in osteoarthritis of the knee, one of the more commonly involved joints, includes a higher lower-extremity–injury rate, differing lower-extremity alignment, lower muscle strength, and the impact of estrogen loss after menopause.

As will be discussed in another section, women are significantly more likely to sustain non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Roos4 noted that women who had sustained an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury were not only significantly more likely to have osteoarthritis of the knee than other women of the same age, they were also more likely to have osteoarthritis than men who had sustained an ACL injury at a similar age. This may reflect differing inflammatory responses at the time of injury or other factors that affect the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Women with radiographic findings of osteoarthritis of the knee, including those without self-reported symptoms, have been noted to have weaker quadriceps than those without such changes; this relationship has not been investigated among men.5 This relative muscular weakness may translate into greater rate and degree of loading or force transmission to articular cartilage.

The impact of estrogen loss on articular cartilage and the consequent development of osteoarthritis has not been clearly defined. Estrogen receptors have been identified on chondrocytes and synoviocytes. Estrogen appears to inhibit production of matrix metalloproteinases and, thus, may help to inhibit cartilage degradation. Articular cartilage defects appear to progress more rapidly in ovariectomized (OVX) rats than they do in native rats; these defects progress more slowly in OVX rats treated with estrogen or SERMs. There are limited clinical studies in humans, and the relative impact of estrogen loss on developing osteoarthritis has not been identified. Estrogen also influences ligamentous laxity, and its loss may represent one of the many factors leading to an increased risk of osteoarthritis among women.

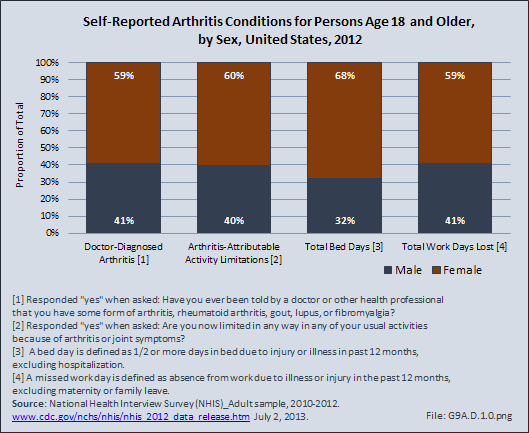

Women are affected by arthritis at a higher rate than are men. Three out of five persons who self-report they have been told by a doctor that they have some form of arthritis are women. Women also are 50% more likely to report they have limitations with activities of daily living because of their arthritis.

Women also report in higher numbers they spent at least one-half day in bed in the previous 12 months due to an arthritis condition, and they reported a higher mean number of days spent in bed (25.7 versus 21.2 days for men). As a result, women accounted for 68% of all bed days attributed to arthritis conditions in 2012.

Although women reported missing work in the previous 12 months due to arthritis in higher numbers than men did, they reported a similar mean number of days lost. Still, women accounted for 59% of total lost workdays in 2012, attributable, at least in part, to an arthritic condition. (Reference Table 9A.4.1 PDF [7] CSV [8])

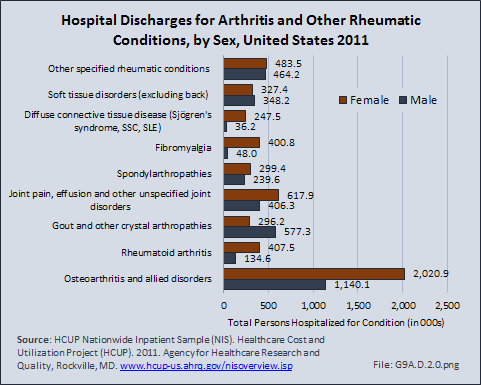

In spite of the frequency and pain severity related to arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (AORC), AORC account for only a small portion of hospital discharges. Visits to a physician’s office or alternative type of care account for the majority of health care related to AORC. However, among the 6.6 million hospital discharges for an AORC in 2011, 60% were women.

Among the nine major conditions defined by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Arthritis Division [9] as AORC, gout is the only condition where men are affected at a higher rate than women (66% of discharges versus 34%). Soft tissue disorders are found in about equal numbers between men and women.

Women are far more likely to have a diagnosis of fibromyalgia (89%) or diffuse connective tissue diseases (Sjögren's syndrome, SSC, SLE) (87%), than are men. Women also accounted for three-fourth (75%) of discharges with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, and two-thirds (64%) of discharges diagnosed with osteoarthritis. (Reference Table 9A.4.2 PDF [10] CSV [11])

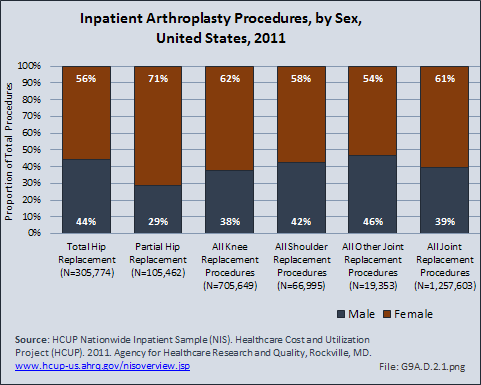

Joint replacement (arthroplasty) procedures are usually performed when osteoarthritis and associated disorders have damaged joints to a point where it is extremely painful to walk and function is impacted. However, there are no objective indications for arthroplasty. Because of the higher rate of osteoarthritis found in women than in men, women are somewhat more likely to receive a joint replacement. (Reference Table 9A.4.2 PDF [10] CSV [11])

Although women receive more joint arthroplasty than do men, some studies have indicated that women are receiving arthroplasty procedures at a lower rate than anticipated, frequently reflecting the impact of gender on health.1 Hawker et al noted that women and men were equally likely to be willing to undergo arthroplasty. They also noted that women were less likely than men to have spoken to a physician regarding joint arthroplasty.1 Other studies noted that women were less likely than men to be referred by their primary care physician for consideration of joint arthroplasty, after controlling for other medical conditions.2,3 These potential delays in joint arthroplasty have significant impact. Katz et al noted that women were significantly more disabled than men by the time they underwent the procedure,4 and Ackerman et al noted that women had a significantly worse quality of life than did men during the time they were waiting for their joint arthroplasty.5 Holtzman et al noted that prior to surgery, more women than men have reported severe pain with walking, needing assistance with walking, needing help with housework, and issues walking across room or less distance; these findings were unrelated to age or comorbidities.6 Although both sexes improve when they have joint arthroplasty, some studies have indicated that women continue to have lower functional scores after surgery than men, potentially reflecting poorer function prior to the procedure and the older age of female patients undergoing arthroplasty. 7,8

Osteoporosis was traditionally thought of as a condition affecting only women. Although approximately 80% of patients with the condition are female, it is being increasingly diagnosed among men. This increased incidence may reflect a greater awareness of the condition among men, rather than a true increase in incidence.

There are significant sex-based differences in osteoporosis. Osteoporosis in men tends to occur at an older age, unless another health condition intervenes. Osteoporosis in women is more likely primary and a result of estrogen loss, while osteoporosis in men is more likely to be secondary to another health condition, especially alcohol over-consumption, loss of testosterone, and use of corticosteroids.

Low impact, or fragility, fractures, frequently occurring as the result of a simple fall, are more common among women, reflecting the higher incidence of osteopenia or osteoporosis. In 2011, 71% of partial hip replacements, most commonly performed to treat hip fractures, were performed on women. (Reference Table 9A.4.2 PDF [10] CSV [11]) For both sexes, the initial fragility fracture is the most significant risk factor for additional fractures and represents an opportunity for secondary prevention. Unfortunately, the likelihood of evaluation and attempts at secondary prevention measures are low for both sexes. However, men, more than women, are even less likely to be evaluated and treated for osteoporosis after the initial fragility fracture.1

For both men and women, low-impact fractures related to poor bone health have significant impact on function, morbidity, and mortality. Vertebral fractures, the most common fracture related to low bone mass, can lead to chronic pain, reduced subjective health status, and limitation in activities. The incidence of vertebral fractures increases with age for both sexes, although this is more pronounced among women.2 After adjusting for age and bone mineral density, sex-based risk for sustaining a vertebral fracture tends to be no longer significant.1 Smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity are known to impact bone health. However, studies examining their association with the risk of vertebral fractures have provided inconclusive evidence of sex-based differences in degrees of impact.3 The rate of mortality also is increased among those sustaining a vertebral fracture. However, Hasserius et al noted that the pattern of differences in mortality differed by sex: increased mortality in women was noted during the first decade after the fracture, especially the first 5 years; the greatest divergence in mortality among men was most significant during the first 3 years after the fracture.4 This is similar to the data available for outcome after fragility fractures of the hip. Hip fractures also lead to increased rates of disability and mortality; however, mortality is substantially higher among men sustaining a hip fracture, especially during the first year after the fracture. These differences in mortality after low-impact fracture, especially in the first few years after fracture, may reflect the differences in etiology of osteoporosis. Men, as previously noted, are more likely to have secondary osteoporosis and be older at the time of fracture; both of these most likely contribute to increased rates of mortality.

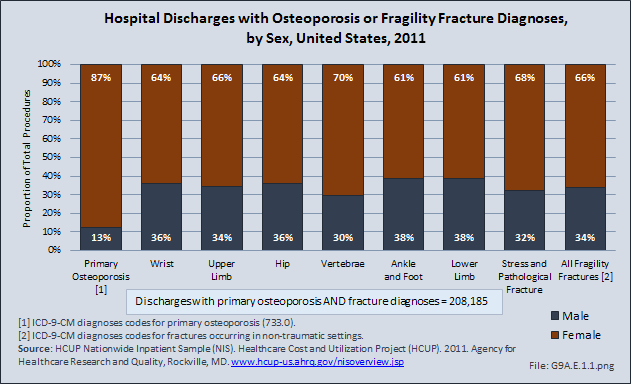

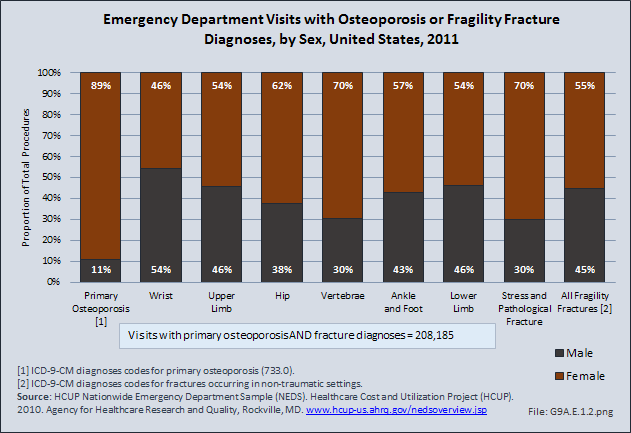

Osteoporosis is often not the principal diagnosis code related to a health care visit, as the condition is usually an underlying cause of another condition, in particular, fragility fractures that often occur after a fall or other seemingly minor incident. Many times in such health care visits, osteoporosis may not even be listed as a condition. Still, in 2011, primary osteoporosis was listed in 2.3 million hospital discharges and emergency department visits as a reason for the visit. Fragility fractures occurred in 4.0 million visits. For 395,500 visits or discharges for fragility fractures, or 10%, primary osteoporosis was also listed as a condition for the visit. The highest proportion of fractures to the vertebrae and stress fractures were diagnosed in women.

Two-thirds of hospital discharges for fragility fractures occurred in women, while 87% of primary osteoporosis diagnoses were in women. Primary osteoporosis was found in a similar proportion of emergency department visits (89%) for women; however, fragility fractures were split 45% males to 55% females.

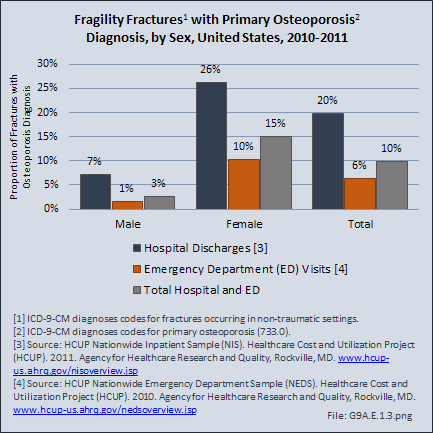

Women also were more likely to have a primary osteoporosis diagnosis with a fragility fracture, accounting for 26% of hospital discharges and 10% of emergency department visits. Among men, both diagnoses were found in 7% of hospital discharges and only 1% of emergency department visits. The noted incidence of osteoporosis among men in this situation is most likely underreported as, noted above, men are less likely than women to be evaluated for osteoporosis, even after sustaining a low impact fracture. Evaluation of bone health in men and women after sustaining a low impact fracture and initiation of secondary fracture prevention measures are areas that require significant attention and improvement. (Reference Table 9A.5 PDF [12] CSV [13])

The most common causes of injury among women are falls, violence, and those related to motor vehicle collisions.1 Men, are more likely than women to present with high impact injuries, such as well as penetrating wounds and open fractures. This most likely reflects the impact of gender on differing levels of exposure to specific high-risk activities. For men and women exposed to the same level of injury, however, sex-based differences have been noted. For example, among athletes exposed to the same degree of head impact, women were more likely than men to sustain a concussion. This has been attributed to differences in strength of the neck muscles and reaction times of the neck muscles.2

The etiology and incidence of some sports-related injuries have been identified between women and men and reflect the impact of sex and gender. Women are more likely than men to present with non-contact injuries, especially those of the ACL. The increased risk of non-contact ACL injuries in women has been attributed to sex-based differences in lower-extremity anatomy and hormonal influences. However, the most likely explanation relates to sex-based differences in neuromuscular control and landing mechanics.3 There may also be gender-based differences in access to appropriate training resources. Sex-based differences in other injuries have been suggested, although significant data has not consistently supported this. Among sports injuries, differing levels of incidence of injury can also be attributed to gender-based differences in the types of sports played or differing rule or mandated safety equipment.

The impact of gender is also noted when assessing the risk of injuries related to intimate partner (domestic) violence (IPV). Women are more likely than men to be victims of IPV. Although physical abuse in this setting is less common than emotional or psychologic abuse, musculoskeletal injuries may bring these women into the health care system, as one-third of women presenting to orthopaedic fracture clinics were found by the PRAISE Investigators to have been victims of IPV of some type within the preceding 12 months.4 This incidence may be underestimated, as most studies in this area rely on self-report and only include those who present for treatment. Among a group of female victims of intimate partner violence, musculoskeletal injuries were the second most common type of injury, following injuries of the head and neck.1 The most common injuries in this setting included contusions, sprains, and fractures/dislocations. Victims of intimate partner violence span all ages, races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

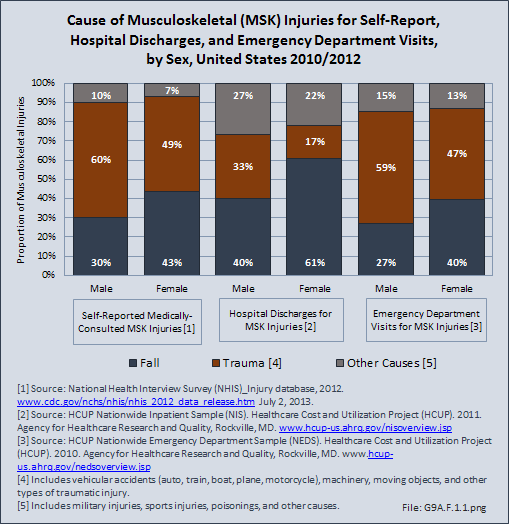

Women are more likely to seek medical care for musculoskeletal injuries that occur from a fall, accounting for as much as 60% of hospital discharges for musculoskeletal injuries. Musculoskeletal injuries to men are more likely to be the result of trauma or an accident, accounting for about 60% of emergency department visits by men. Sports injuries and other causes of injuries occur in relatively similar proportions to both men and women. (Reference Table 9A.6 PDF [14] CSV [15])

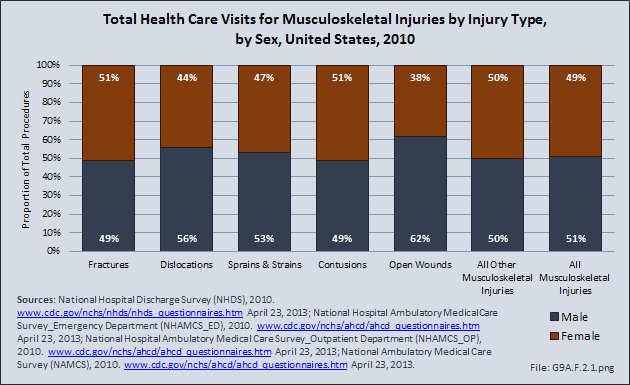

In 2010, 65.8 million health care visits were made to hospitals, emergency departments, outpatient clinics, and physician’s offices for musculoskeletal injuries. These visits were split nearly evenly between women and men (49% to 51%, compared to US census population of 51% to 49%, females to males). This distribution differed only a few percentage points for all types of musculoskeletal injuries, with the exception of open wounds, with 62% occurring to men. (Reference Table 9A.6 PDF [14] CSV [15])

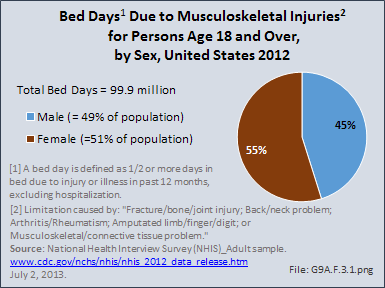

Women report more bed days due to musculoskeletal injuries than men do, both in number of women with bed days and the mean number of bed days reported. In 2012, women self-reported a mean of 10.5 bed days versus a mean of 8.0 days for men. Overall, women accounted for 55% of the 99.9 million bed days reported for musculoskeletal injuries in 2012.

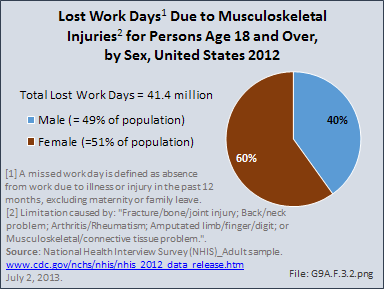

Although a lower number of women than men reported lost workdays due to musculoskeletal injuries in 2012, they reported a mean of 11.5 days lost versus the 7.4 mean days lost reported by men. As a result, women accounted for 60% of the 41.4 million self-reported lost workdays in 2012 due to musculoskeletal injuries. (Reference Table 9A.6 PDF [14] CSV [15])

Primary sarcomas represent the least common malignancies in bone, although osteosarcoma represents the most common nonhemoapoietic primary tumor of bone. Slightly higher incidences of males have been reported for osteosarcoma (53% male versus 47% female) and Ewing sarcoma, the second most common bone and soft tissue sarcoma of young patients (55% male versus 45% female); neither is statistically significant. However, in the more common malignant lesions in bone—metastatic disease and myeloma—various studies have noted differing incidences and/or differences in outcome between the sexes.

Survival among patients with cancers continues to improve, increasing the risk for metastases. Bone is a common site of metastasis for most malignancies, and metastatic carcinoma represents the most common malignancy in bone. These typically are harbingers for poor prognosis. In addition, related skeletal events (hypercalcemia, pathologic fracture, bone pain necessitating radiation therapy, surgical intervention, spinal cord compression) lead to significant morbidity and impact on patient function, as well as shorter median survival times. Carcinomas that occur in both men and women and have a propensity for skeletal metastasis, including lung, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, have reported differing incidences between men and women of risk, location, and outcome of bone metastasis. For example, men are almost twice as likely to develop acrometastasis,1 with more than half representing metastatic lung carcinoma, reflecting the higher incidence of lung cancer among men.2

Lung cancer is a leading cancer globally, and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Men are more likely to develop lung cancer; however, women tend to be younger and less likely to be smokers, than men with lung cancer are. It has also been noted that men are more likely to have squamous cell subtype of lung carcinoma.3 Sex-based differences have not been consistently identified in the risk of metastasis or skeletal-related events (SRE), including among patients initially presenting with extensive disease,4 perhaps reflecting the shorter life expectancy among these patients.3,5 In some studies of patients with bone metastasis, women have been noted to have longer average survival than men; however, sex does not consistently remain an independent predictor of survival after accounting for younger age at diagnosis, non-smoker status, and adenocarcinoma cell type, all factors associated with improved survival and more commonly noted among women.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women; only 1% of cases of breast cancer are diagnosed in men. Men tend to be older at the time of initial diagnosis. Approximately 5% of women will present with metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis, with another 4% developing bone metastasis during follow-up. In contrast, more than 40% of men present with stage III or IV disease.6 Presentation of men at later stages of disease may reflect the impact of screening programs and greater awareness of the disease in women. For both sexes, bone is the most common location of metastasis, with approximately half of women sustaining a skeletal-related event during the course of their disease. Similar data for SREs are not available for men. Bone metastases and SREs have significant impact on survival.7 Sex has been found to be an independent risk factor for prognosis, with women having better survival. However, this may reflect the more advanced stage at the time of initial diagnosis among men because, after controlling for stage, men have been reported to have similar rates of survival as women.8 In contrast, others have suggested that the tumor biology differs between the sexes because men have been noted to have worse survival than women among those with early stage or lymph-node–negative tumors and among those with estrogen-receptor–positive tumors.6 The relative impact on survival of different tumor biology and greater awareness and screening needs to be further elucidated.

Renal cell carcinoma represents approximately 4% of new cancer diagnoses each year in the United States.9 Approximately one-third of patients will present with metastatic disease, with another one-third developing metastases later. Bone is the second most common site of metastasis, after lung; between 20% and 35% of patients will have bone metastases during the course of their disease, with 85% eventually developing an SRE.10 Although there is a higher incidence of renal cell carcinoma among men (male:female, 1.5:1), the male:female ratio increases among those with metastases at other sites (2.0) and is even higher among those with bone metastases (2.4).10 However, sex has not been identified as an independent risk factor for survival,11 including among patients with bone metastases.9

Myeloma is the most common malignancy arising in bone. Changes in bone arising from myeloma can result in osteolytic lesions, osteopenia, bone pain, and hypercalcemia. The incidence of myeloma increases with age. Men are more often diagnosed with myeloma than are women, with this sex difference initially noted at the age of 40 years. The male:female ratio increases with each decade, and is highest among those 85 years of age and older. Myeloma is also more common among Blacks for both men and women. A possible impact of female hormones on the immune system and secondary impact on the incidence of myeloma has been suggested.12 Older studies noted that males with myeloma had an increased estrogen:androgen ratio and women with myeloma had a decreased estrogen:androgen ratio, compared to controls.13 More recent studies have attempted to investigate the impact of sex hormones on the development of myeloma by correlating reproductive history with subsequent myeloma risk; results of these studies has been inconsistent, with some suggesting that increased parity is associated with increased risk of developing myeloma.12

Anthropometric characteristics14 have also been investigated in incidence of myeloma. The impact of height was found to be correlated to myeloma risk in women but not in men,15 or to have no effect on risk for either sex.16 Body mass index was reported to be related to myeloma risk in men but not women.15 However, other studies have noted that a higher BMI is related to poorer prognosis among women but not men.16 Sex-based differences in the prevalence of genetic mutations in myeloma have also been reported; immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) translocations were found to be more common in women, and hyperdiploidy was more common in men. There were also differences in secondary genetic events with del(13q) and +1q being found more frequently in female myeloma patients.16 It has been suggested that mutations associated with poor prognosis may explain, in part, the lower overall survival noted among women with myeloma.

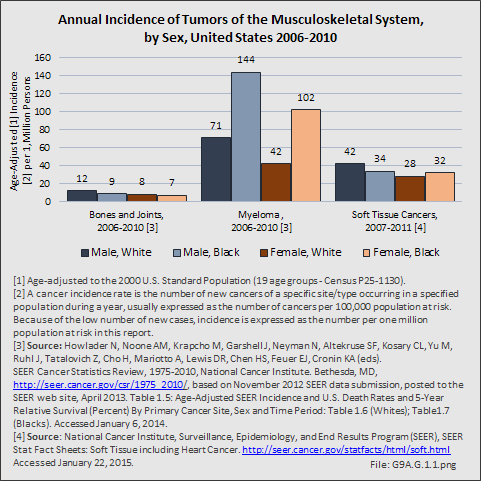

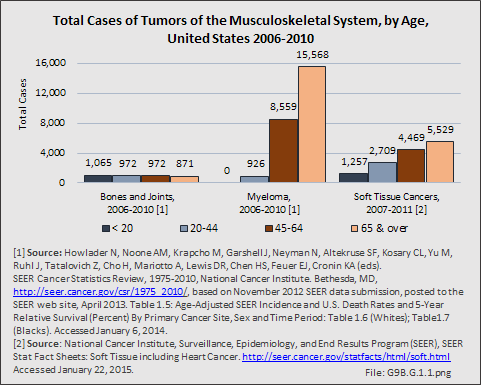

Men have a higher incidence of all types of musculoskeletal system tumors than women do. The difference is particularly noticeable in the incidence of myeloma, with both White and Black men being 30% to 40% more likely to have myeloma than White or Black Women. (Reference Table 9A.7 PDF [16] CSV [17])

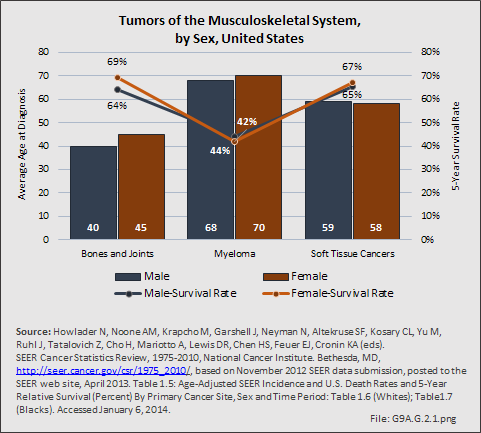

In addition to higher incidence rates, men also are likely to be diagnosed with all types of musculoskeletal system tumors a few years younger than women. Myeloma, the most common of the musculoskeletal system cancers, is primarily a disease of the elderly, while soft tissue cancers in middle age, and cancers of bones and joints in children and young adults.

Men have a slightly lower 5-year survival rate for bone and joint cancers and soft-tissue cancers, both of which have a survival rate of 64% to 70%. Women have a slightly lower 5-year survival rate for myeloma, which has a rate of 42% to 44%. (Reference Table 9A.7 PDF [16] CSV [17])

The relative impacts of sex and gender on etiology and responses to treatment need to be defined for all musculoskeletal conditions. Evidence at this point indicates that women experience musculoskeletal conditions in higher numbers than men do for all conditions except traumatic injuries and cancers of the musculoskeletal system. The smaller differences such as those found in musculoskeletal injuries and spine conditions are moderate. Differences in incidence for some conditions, such as osteoporosis, spinal deformity, and arthritis, are sufficient to warrant exploration into reasons why these differences occur.

The impact of sex on musculoskeletal conditions may reflect differences in levels of or response to sex hormones. However, the relative impact of these hormones between the sexes and during different phases of the menstrual cycle have not been clearly elucidated, and although it is likely sex hormones impact on most, if not all, musculoskeletal conditions, additional factors need to be investigated. As the Institute of Medicine says, “every cell has a sex,”1 and these cell-based differences reflect much more than response to sex hormones. Identification of sex-based factors related to causes of disease will be key to prevention. Sex-based differences in responses to treatment may indicate a need to tailor treatment options to individual patients. The latter is exemplified by the significant differences between the sexes in outcome of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty,2 which may also be influenced by sex-based genetic differences.3 In addition, the impact of gender needs to be clarified. Although prevention and treatment options are available, if there is not awareness that these conditions occur in all patients, and patients of either gender are less able or not encouraged to access these resources, the outcome of their treatment is less likely to be delayed, impacting function, and raising the societal costs of these conditions.

While significant data exists regarding sex-based differences in some musculoskeletal health conditions, the presence of these differences should be assessed for all conditions. Where differences are noted, additional research is needed to identify how sex- and gender-based differences may influence etiology and presentation of conditions. This would facilitate diagnosis, as well as tailor prevention and treatment modalities to individual patients, decrease incidence of these conditions, improve outcome, and lead to enhanced function.

Demographic changes have created an urgent need. The growth in the number and proportion of older adults is unprecedented in the history of the United States. Two factors—longer life spans and aging boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964)—will combine to double the population of Americans age 65 years or older during the next 25 years to about 72 million. By 2030, older adults will account for roughly 20% of the US population.

Chronic conditions present a strong economic incentive for action. During the past century, a major shift occurred in the leading causes of death for all age groups, including older adults, from infectious diseases and acute illnesses to chronic diseases and degenerative illnesses. More than a quarter of all Americans, and two of every three older Americans, have multiple chronic conditions. Treatment for this chronic-conditions population accounts for 66% of the country’s healthcare budget.1

Mobility is fundamental to everyday life and central to an understanding of health and well-being among older populations. Impaired mobility is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes. As the age of the US population continues to increase, aging and public health professionals have a growing role to play in improving mobility for older adults. There are critical gaps in the assessment and measurement of mobility among older adults who live in the community, particularly those who have physical disabilities or cognitive impairments. By changing the physical environment in which older people live and creating unique integrated interventions across various disciplines, we can improve mobility for older adults.

As expected, the aging population is prone to higher rates of nearly all musculoskeletal conditions than those found in younger people. In large part, these conditions can be attributed to wear and tear on bones and joints over a lifetime. However, some musculoskeletal conditions such as back pain are equally prominent in younger age populations, particularly those in their middle ages.

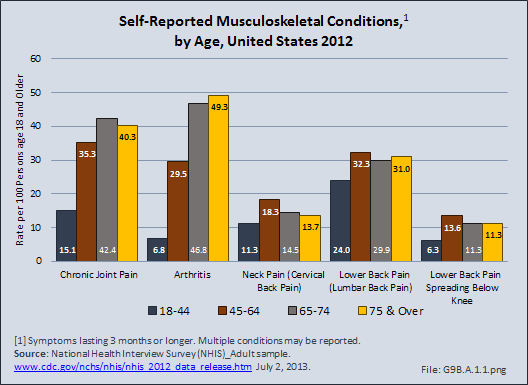

Arthritis is self-reported in 2012 at the highest among persons aged 75 years and older (49%), but by nearly as many in the 65- to 74-year age range (47%). Only 30% of ages 45 to 64 years self-report they have a form of arthritis. Chronic joint pain, however, is reported at the highest rate by the 65- to 74-year age group, with both those aged 75 years and older and 45 to 64 years reporting rates of chronic joint pain at close to this rate. Low back pain, on the other hand, was self-reported at the highest rate by persons aged 45 to 64 years, closely followed by all persons age 65 years and older. Overall, 126.6 million people age 18 years and older self-reported one or more types of musculoskeletal conditions in 2012. (Reference Table 9B.1 PDF [20] CSV [21])

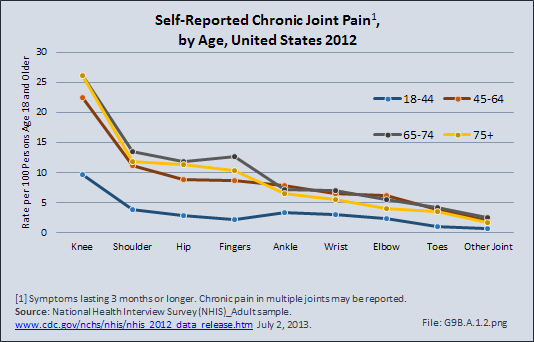

The most common chronic joint pain reported by the 63.1 million people of all ages is knee pain, followed by shoulder pain. However, the rate per 100 people reporting chronic pain in specific joints varies by age. Knee pain is reported by 22% to 26% of people age 45 years and older, with these age groups reporting shoulder pain at rates of 11% to 13.5%. Hip and finger joint pain are both reported at higher rates by people age 65 years and older, while ankle pain has the highest rate among people aged 45 to 64 years. Joint pain in the ankle, wrist, elbow, and toes is lower among those in the oldest age group, compared to those 45 to 74 years of age, possibly due to being less active and placing lower stress on these joints. (Reference Table 9B.1 PDF [20] CSV [21])

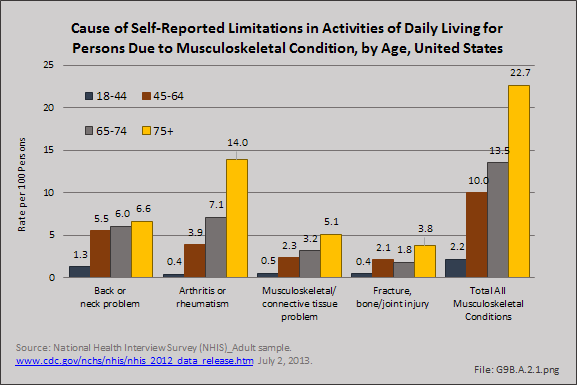

An estimated 6 in 100 persons report they have limitations performing activities of daily living such as dressing, bathing and walking due to musculoskeletal conditions. However, the rate with limitations rises steadily as the population ages, from just over 2 in 100 for those age 18 to 44 years, to 23 in 100 for people who have reached the age of 75 years. The highest rate of limitation is due to arthritis in the oldest group, but due to back or neck problems in the younger ages. (Reference Table 9B.1 PDF [20] CSV [21])

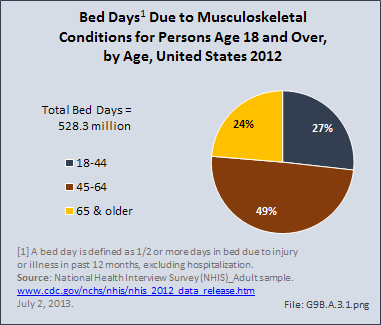

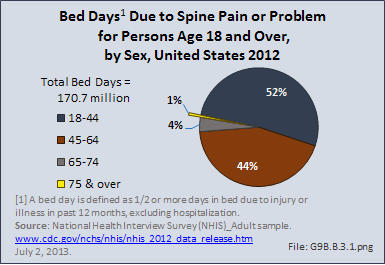

People age 45 to 64 years accounted for one-half (49%) of the 528.3 million bed days from a musculoskeletal condition that were reported in 2012 by people age 18 years and older. A bed day is defined as one-half or more days in bed due to injury or illness, excluding hospitalization. The greater number of total bed days reported by this age group is due to a high mean of 10.4 days combined with close to half the population reporting bed days because of a musculoskeletal condition. (Reference Table 9B.1 PDF [20] CSV [21])

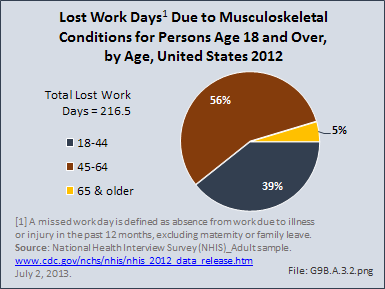

This same age group also accounted for slightly more than half (56%) of the 216.5 million lost work days due to musculoskeletal conditions reported by people age 18 years and older and in the workforce. People aged 65 years and older reported only 5% of total lost work days because of the low number that are still in the workforce. (Reference Table 9B.1 PDF [20] CSV [21])

Older adults will often experience musculoskeletal diseases affecting the spine, with spondyloarthritis and osteoporosis with vertebral fractures often the cause of pain and functional decline. Seniors with such problems may find themselves unable to push or pull large objects, or at times even reach above their heads. They may have problems lifting groceries from the floor, and bending at the waist may increase the risk for vertebral fractures in people with osteoporosis. Additionally, thoracic vertebral fractures (middle back) will result in decreasing functional vital capacity, predisposing older adults to chronic lung disease and pneumonias.

Self-reported back and neck pain rates peaked in the age range of 45 to 64 in 2012, and were reported at slightly lower rates for persons age 65 years and older. Roughly one in three people aged 45 years and older reported back or neck pain.

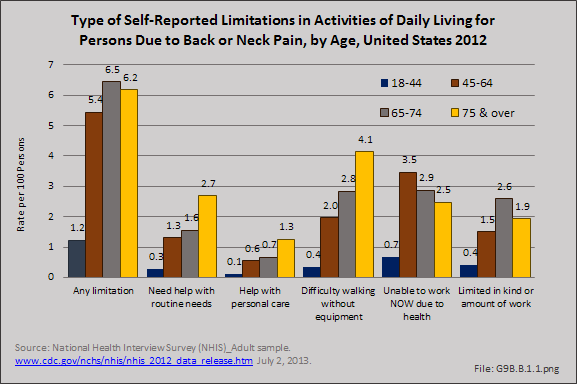

About 4 in 100 persons reported limitations with activities of daily living due to a chronic back or neck problem, with the highest rate (6.5 in 100) among people aged 65 to 74 years. The oldest population, those aged 75 years and older, have most difficulty walking without equipment (4.1 in 100) due to back pain. People aged 45 to 64 years reported the highest rate (3.5 in 100) of being unable to work because of chronic back and neck problems, while people aged 65 to 74 years reported the highest rate (2.6 in 100) with limitations in kind or amount of work. (Reference Table 9B.2.1 PDF [22] CSV [23])

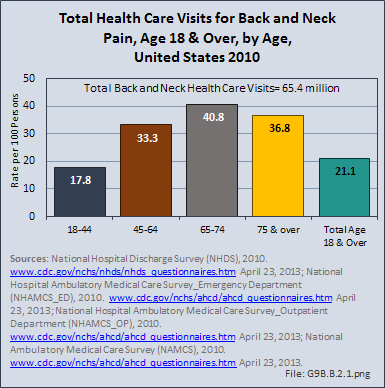

People aged 65 to 74 years had the highest rate of healthcare visits for back and neck pain (40.8 per 100 persons), but accounted for only 14% of the 65.4 million total healthcare visits made by adults for back or neck pain in 2010, due to their smaller share of the total population. The rate of healthcare visits was similar for people aged 75 years and older (36.8 per 100) and those aged 45 to 64 years (33.3 per 100). While only 17.8 in 100 people ages 18 to 44 years had a healthcare visit in 2010 for back and neck pain, this age group comprised 31% of all visits. Total healthcare visits included hospital discharges, emergency department (ED) and outpatient clinic visits, and physician office visits.

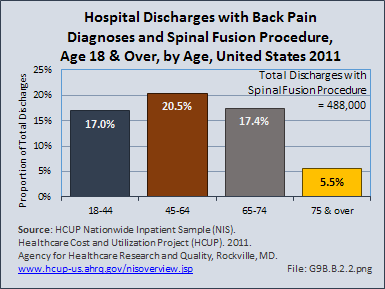

Those aged 45 to 64 years had the highest rate of spinal fusion procedures performed for back or neck pain. One in five, or 20.5%, of hospital discharges in this age group with a back or neck pain diagnosis had a spinal fusion procedure performed. People aged 75 years and older have a low rate of spinal fusion procedures (5.5%). (Reference Table 9B.2.2 PDF [24] CSV [25])

People aged 65 years and older account for only a small share (0.7%) of people who report taking a bed day due to spinal pain or problems, in spite of the number who report having pain. Younger people, aged 18 to 45 years, account for slightly more than half (52%) of the total 170.7 million bed days taken in 2012 due to back pain. (Reference Table 9B.2.1 PDF [22] CSV [23])

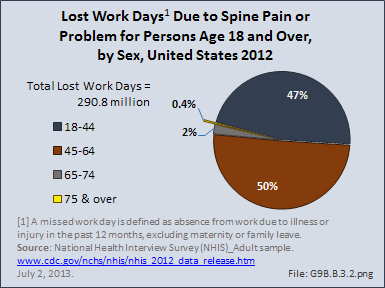

Lost work days due to spine pain or problems in 2012 were taken primarily by people aged 18 to 64 years, the prime workforce ages, and split nearly equally between those under and over the age of 45 years. In 2012, 290.8 million work days were reported lost due to back pain. (Reference Table 9B.2.1 PDF [22] CSV [23])

This report includes a range of deformity conditions that affect the spine. The most common spinal deformity in older adults is acquired through multiple vertebral fractures resulting in kyphosis. For each thoracic vertebral fracture, it is estimated there is an estimated decline of 7% in functional vital capacity1, which is compounded by additional fractures. Vertebral fractures are often clinically unrecognized, and may show merely as height loss. Nonetheless, vertebral fractures greatly increase the likelihood of future fractures and mortality.2,3

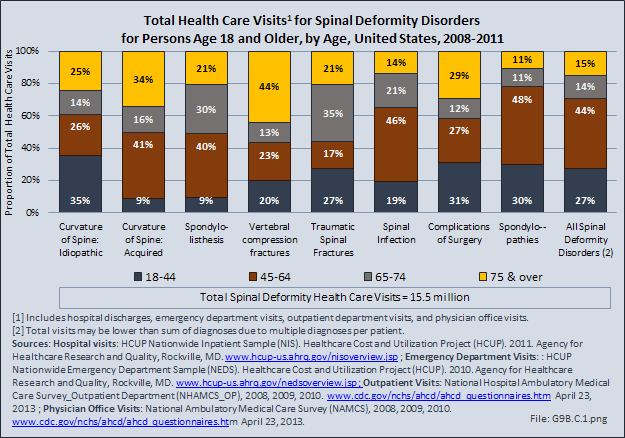

The most familiar spinal deformity condition is that of curvature of the spine, which includes scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis. In addition to curvature of the spine, other spinal deformity conditions include spondylolisthesis, spinal infections, complications of surgery, and spondylopathies. Of the 15.5 million health care visits for spinal deformity, 10.5 million had a diagnosis of spondylopathy, which refers to any disease of the vertebrae or spinal column associated with compression of peripheral nerve roots and spinal cord, causing pain and stiffness.

The oldest age group, people aged 75 years and older, account for the largest share of vertebral compression fractures (44%) and a major portion (34%) of acquired curvature of the spine, even though they represent only 8% of the population aged 18 years and older. They also account for a large share (29%) of spondylopathy diagnosis as well as 25% of idiopathic curvature of spine diagnosis; this is overall a larger share of all spinal deformity diagnoses than expected for the size of this age group.

People aged 65 to 74 years comprise 9% of the population over 18 years of age. This group also has a higher than expected share of healthcare visits for all spinal deformity diagnoses. The two conditions that stand out in this age group are traumatic spinal fractures (35% of total visits) and spondylolisthesis (30% of all visits).

On an annual average, 15.5 million healthcare visits were made between the years 2008 and 2011 by people aged 18 years and older. Those aged 45 to 64 years, 35% of the population aged 18 years and older, were treated in 44% of these visits. (Reference Table 9B.3 PDF [26] CSV [27])

Arthritis is one of the most common chronic conditions found in the US population. It currently affects 46 million US adults and is projected to increase 45% by 2030. It is the most common cause of disability in the United States, substantially affecting a person’s quality of life due to pain causing work and activity limitations, which subsequently affects the economy.

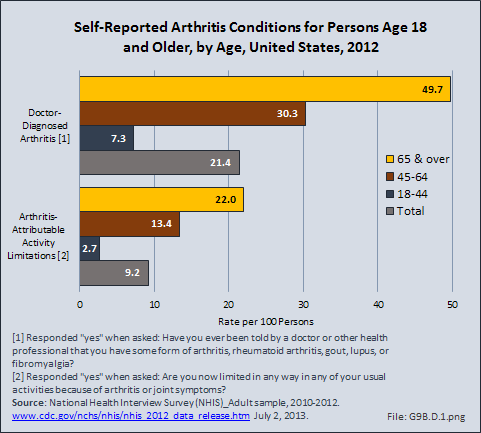

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC) affect people in higher numbers as they age. Only 7 in 100 persons between the ages of 18 and 44 years report they have doctor-diagnosed arthritis. By the age of 65 years and older, this rate has increased to one in two with some form of arthritis. Although the rates of persons reporting limitations in performing activities of daily living are lower, there is a large disparity between younger persons and the aging. (Reference Table 9B.4.1 PDF [28] CSV [29])

Bed days occur when a person spends at least one-half day in bed in the previous 12 months due to a health condition. In 2012, 537.6 million bed days were reported by persons age 18 years and older due to arthritis. Only 4% of people aged 18 to 44 years reported arthritis-caused bed days. For all people aged 45 years and older, the rate was between 14% and 16%.

Arthritis is most likely to be the cause of lost work days among people between the ages of 45 and 64 years, with nearly 1 in 10 reporting work days lost. In 2012, 172.1 million work days were reported lost due to arthritis, with 65% lost by people in the 45- to 64-year age group. Likely, this higher share of lost work days for this group is due to the much higher participation in the workforce for this prime working age cohort. (Reference Table 9B.4.1 PDF [28] CSV [29])

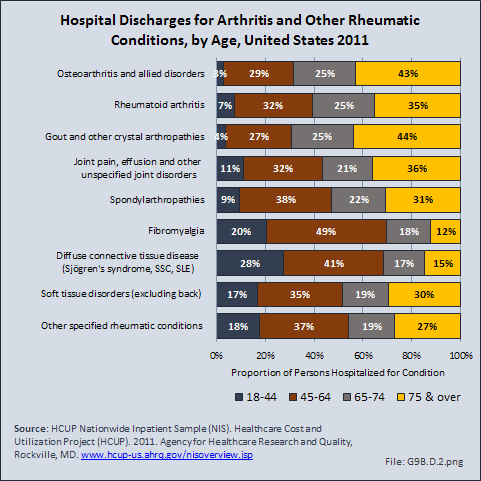

In spite of the frequency and severe pain often experienced with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, these illnesses account for only a small portion of hospital discharges. Visits to a physician’s office or alternative types of care account for the majority of health care related to AORC, with more than 100 million ambulatory visits in 2010. Among the 6.6 million hospital discharges for an AORC in 2011, age was a factor in increasing rates of hospitalization. Fewer than 1 in 100 persons ages 18 to 44 years had a hospital discharge with a diagnosis of an AORC, while 13 in 100 aged 75 years and older were discharged with an AORC diagnosis.

Osteoarthritis is the primary form of arthritis to affect older persons, and begins to show increasing rates for people in their 60s. By the age of 75 years, multiple forms of arthritis are often diagnosed and categorized as other rheumatic conditions. (Reference Table 9B.4.2 PDF [30] CSV [31])

Age is not a factor in the length of hospital stay or mean charges with a diagnosis of an AORC. In general, the type of AORC is also not a factor in length of stay or charges, with the exception of a diagnosis of spondylarthropathy, which results in slightly higher mean hospital charges. Hospital charges are a rough estimate of hospital cost, and do not include doctor’s fees. (Reference Table 9B.4.2 PDF [30] CSV [31])

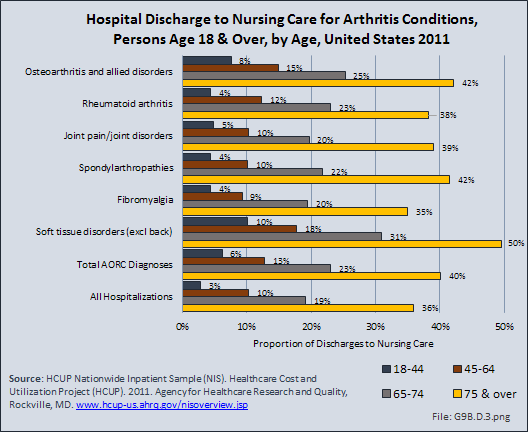

Discharge from a hospital to short- or long-term care is a major healthcare cost. The frequency of this increases significantly with age, and is more likely to occur with an AORC diagnosis than for all causes of hospitalization. One in eight people age 45 to 64 years discharged from a hospital with a diagnosis of an AORC is sent to intermediate-term or skilled nursing care. This increases to one in four for persons aged 65 to 74 years, and two in five for ages 75 years and older. The most likely AORC to result in nursing care is a soft tissue disorder, but all causes of AORC result in nursing home care for 35% or more of discharges among patients aged 75 years and older. (Reference Table 9B.4.3 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Osteoporosis means "porous bone." It is a condition that develops when more bone calcium is absorbed than is replaced in the normal bone remodeling process. Several factors contribute to the development of osteoporosis, but the exact reason why the remodeling process becomes unbalanced is unknown. Factors that often lead to osteoporosis include aging, physical inactivity, reduced levels of estrogen, excessive cortisone or thyroid hormone, smoking, and excessive alcohol intake. Loss of bone calcium accelerates in women after menopause.

Bone loss occurs most frequently in the spine, lower forearm above the wrist, and upper femur or thigh, the site where hip fractures usually occur.

Standard Definitions for Osteoporosis Diagnosis:

Low bone mass: A value for bone mineral density more than 1 standard deviation (SD) below the young female adult mean but less than 2.5 SD below this value.1

Osteoporosis: A value for bone mineral density 2.5 SD or more below the young female adult mean.2

Young female adult mean and standard deviation (SD): For the femoral neck, the mean and SD were based on data for 20- to 29-year-old non-Hispanic white females from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).3 For the lumbar spine, the mean and SD were based on data for 30-year-old white women from the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) densitometer manufacturer.4

Other races: People from racial and ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Mexican American. This group consists primarily of Hispanic descent other than Mexican American, Asian, Native American, and multiracial persons, among others.

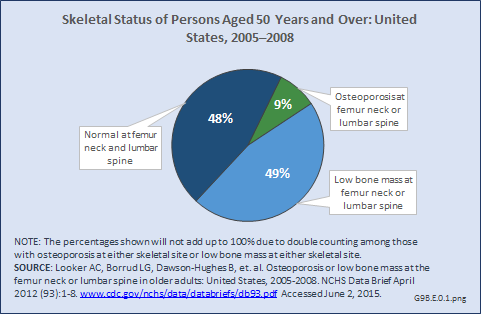

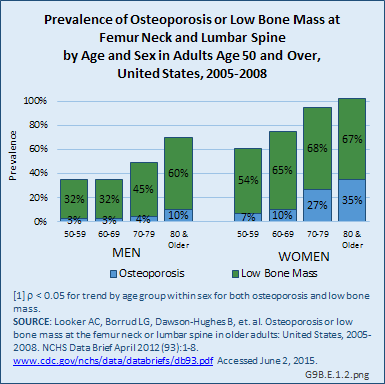

Nine percent of people aged 50 years and older had osteoporosis at either the femur neck or lumbar spine from 2005 to 2008 (Figure 1). Roughly one-half of older adults in the population had low bone mass at either the femoral neck or lumbar spine. Forty-eight percent of older adults in the United States had normal bone density at both the femur neck and lumbar spine.

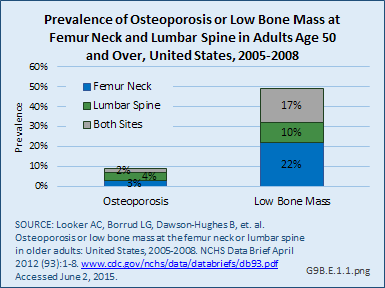

From 2005 to 2008, the prevalence of osteoporosis in women aged 50 years and older at either the femur neck or lumbar spine was 9%, with 4% with osteoporosis at the lumbar spine only, 3% with osteoporosis at the femur neck only, and 2% with osteoporosis at both the lumbar spine and femur neck. The prevalence of low bone mass at either skeletal site was 49%, with 10% having low bone mass at the lumbar spine, 22% with low bone mass at the femur neck, and 17% with low bone mass at both the lumbar spine and femur neck.

Age is a significant factor in the presence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in both men and women, but particularly in women. By the age of 70 years, virtually all women have low bone mass, with 27% or more having osteoporosis. In men, the prevalence of osteoporosis does not begin to increase until the age of 80 years, although low bone mass begins to climb for men in their 70s.

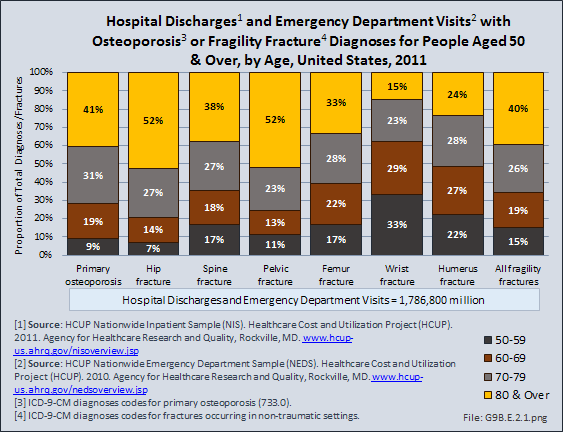

Osteoporosis often is not the principal diagnosis code related to a healthcare visit because the condition is usually an underlying cause of another condition, in particular, fragility fractures that often occur after a fall or other seemingly minor incident. Many times in such healthcare visits, osteoporosis may not even be listed as a condition. Still, in 2011, primary osteoporosis was listed in 1.8 million hospital discharges and emergency department visits as a reason for the visit in the population aged 50 and over. Fragility fractures occurred in 1.2 million visits for people aged 50 years and older. (Reference Table 9B.5 PDF [34] CSV [35])

Age is a factor in both primary osteoporosis diagnosis and in the occurrence of fragility fractures with most occurring in people after the age of 70. Nearly three-fourths (72%) of primary osteoporosis diagnoses were for people ages 70 years and older. However, in 2011, 9% of osteoporosis diagnoses was for people aged 50 to 59 years, and 19% of those aged 60 to 69 years. Among fragility fractures, 66% were for people aged 70 years and older, with the remainder split among those aged 50 to 69. The site of the fracture was particularly important with respect to age. The oldest group, those 70 years and older, were prone to fractures of the hip and vertebrae, as well as stress and pathological fractures. Fractures of the wrist and ankle or foot occurred across all people over the age of 50.

For 340,400 emergency department visits or hospital discharges for fragility fractures, or 16%, primary osteoporosis was also listed as a condition. The rate at which both diagnoses were made rose steadily as the population aged. Hospital discharge visits were more likely to include both primary osteoporosis and a fragility diagnosis than were visits to an emergency department.

Fractures are associated with significant increases in health services utilization compared to prefracture levels. Relative to the prior 6-month period, rates of acute hospitalization are between 19.5 (distal radius/ulna) and 72.4 (hip) percentage points higher in the 6 months after fractures. Average acute inpatient days are 1.9 (distal radius/ulna) to 8.7 (hip) higher in the postfracture period. Fractures are associated with large increases in all forms of postacute care, including postacute hospitalizations (13.1% to 71.5%), postacute inpatient days (6.1% to 31.4%), home health care hours (3.4% to 8.4%), and hours of physical (5.2% to 23.6%) and occupational (4.3% to 14.0%) therapy. Among patients who were initially community dwelling at the time of the initial fracture, 0.9% to 1.1% were living in a nursing home 6 months after the fracture. These rates rose by 2.4% to 4.0% one year after the fracture.1

INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Since 1980, there has been a nearly 15% decrease in the prevalence of chronic disability and institutionalization among people aged 65 years and older. A drop in disability translates directly into cost savings since it is seven times more expensive to care for a disabled senior versus a healthy one. Major activity limitations are a common cause of nursing home admissions. While the most common cause of limitations is arthritis, affecting nearly 50% of people older than 65 years and an estimated 60 million by 2020.2 Hip fractures are a second source of immobility, and are projected to reach 289,000 in the year 2030, nearly all fall-related.3

FRACTURES AND MORTALITY

Vertebral and hip osteoporotic fractures result in a 20% increase in mortality, usually observed in the 12 months after the fracture. Men, who are generally older at the time of the hip fracture, have a 30% mortality rate after the fracture. Moreover, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease contribute to a higher mortality rate.

A population-based study in Olmsted County, MN, found that within the first seven days after hip fracture repair, 116 (10.4%) of participants experienced myocardial infarction and 41 (3.7%) subclinical myocardial ischemia. Overall, the 1-year mortality was 22%, with no difference between those with subclinical myocardial ischemia and those with no myocardial ischemia. One-year mortality for those with a myocardial infraction was significantly higher (35.8%) than for the other two groups.4 The relative mortality after vertebral fracture varies from 1.2 to 1.9 in different reports,5,6 but the excess deaths occur late, rather than early, after vertebral fractures.5

For older adults, falls and associated injuries threaten health, independence, and quality of life. More than a third of people aged 65 years and older who live independently fall each year; falls are the leading cause of injury-related deaths and hospital emergency department visits.

While numerous fall risk factors have been identified, limited information is available about the detailed circumstances surrounding falls among community-dwelling older adults. Several studies have used survey data to analyze falls, while other studies have limited their analysis to falls seen in emergency departments, in older women, or falls that resulted in fracture or hip fracture.

More than 6.8 million injury episodes for which people sought medical treatment were self-reported by individuals in 2012. The majority of injuries occurred to people between the ages of 18 and 64 years, the ages that comprised 83% of the over-18-year population in the United States. Sprains and strains was the most frequent injury type for which medical care was sought, but 16% suffered fractures, 14% severe contusions, and 13% open wounds.

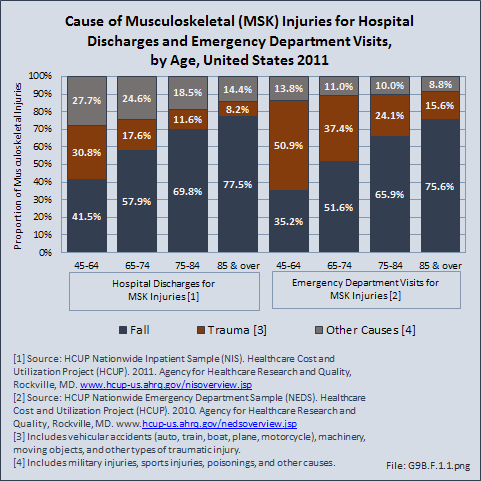

Falls are the primary cause of musculoskeletal injuries as the population ages. Approximately three out of four injuries among people aged 85 years and older for which a person is hospitalized or visits an emergency department is the result of a fall. Falls are also the primary cause of injury for anyone aged 65 years and older. Trauma such as auto accidents and other accidents involving machinery or moving objects is a major cause of musculoskeletal injuries among people ages 45 to 64 years, particularly for injuries where care is received in an emergency department. Other causes of injuries, including sports injuries, are seen in more than one in four (28%) injuries to people aged 45 to 64 years with a hospital discharge. (Reference Table 9B.6.1 PDF [38] CSV [39] and Table 9B.6.2 PDF [40] CSV [41])

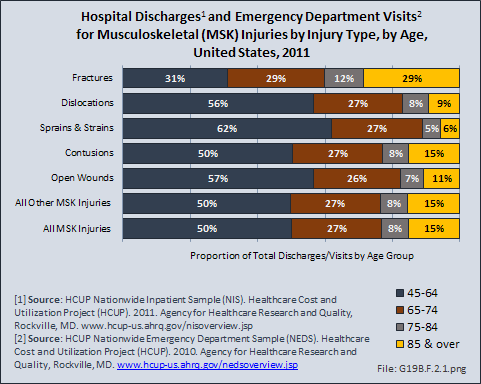

In 2011, 1.6 million hospital discharges and 14.7 million emergency department visits were made by people aged 18 years and older for treatment of a musculoskeletal injury. Another 35.5 million musculoskeletal injuries were serious enough to receive outpatient treatment. The most frequent type of injury involving hospitalization was a fracture, with people aged 85 years and older accounting for 45% of hospitalizations for fractures. Injuries seen in emergency departments were distributed across all types of musculoskeletal injuries (fractures, dislocations, sprains and strains, contusions, open wounds, and other types of musculoskeletal injuries). The youngest and oldest age groups (18 to 44 years and 85 years and older) had the highest rate of injury seen in the ED (6.9/100 persons and 9.9/100, respectively). Because of the large size of the 18- to 44-year age group (48% of the US population is over age 18), this group constituted a majority of all injury cases seen, with the exception of fractures. (Reference Table 9B.6.2 PDF [40] CSV [41] and Table 6A.2.2.2 PDF [42] CSV [43])

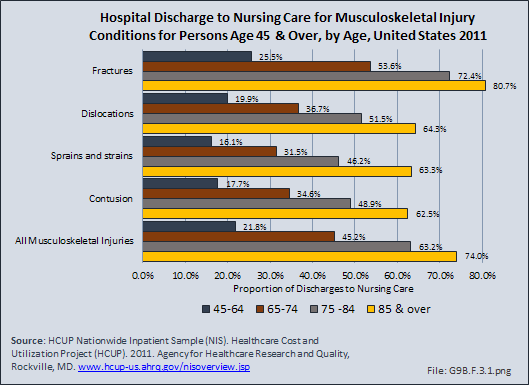

For all types of musculoskeletal injuries resulting in hospitalization, three of four people ages 85 years and older were discharged to intermediate-term nursing care, while two in three aged 75 to 84 years went to nursing care. Fractures were the most likely type of injury to result in discharge to intermediate-term nursing care for all ages, followed by dislocations. (Reference Table 9B.6.3 PDF [44] CSV [45])

Discharge to intermediate-term or skilled nursing care greatly increases the economic burden of musculoskeletal injuries. In 2011, 40% of hospital discharge patients with a musculoskeletal injury, or 690,000, were sent to long-term or skilled nursing facilities.

Osteogenic sarcoma exhibits a bimodal distribution, with the significant second peak in incidence occuring in the seventh and eighth decades of life. Osteosarcoma in the elderly can also be attributed to Paget’s disease or previous radiotherapy. The expectation that these elderly patients may not tolerate aggressive modern chemotherapy means that those who develop OS over the age of 40 years are excluded from current treatment trials. As a result, remarkably little is known about the outcome for this age group.1

The overall incidence of tumors of the musculoskeletal system is lower than many types of cancers. This is particularly true for primary cancers of the bones and joints, although bones and joints are frequently a site of secondary, or metastasized, cancers. The occurrence of cancers of the bones and joints affects all ages and is one of the primary cancers in young people. Myeloma, cancer of the bone marrow, is a disease of the elderly, with nearly two-thirds of cases found in people ages 65 years and older. Soft tissue cancers affect all ages, but the occurrence increases with age. (Reference Table 9B.7 PDF [46] CSV [47])

Key challenges in the area of musculoskeletal health in older adults are considerable because we have a dramatic increase in older adults and prolonged life expectancy, greatly increasing the likelihood of development of arthritis, osteoporosis, and other musculoskeletal disorders.

A growing body of work on health-related knowledge translation reveals significant gaps between what is known to improve health and what is done to improve health. The costs of ignoring these gaps are increasingly apparent: suboptimal or unnecessary care, overuse or premature adoption of treatments, and new research that may not be based on the latest evidence or may not adequately address patient needs.

A gap in medical care occurs after an osteoporosis-related fracture in older adults. Furthermore, decreasing rate of treatment for osteoporosis after hip fracture is noted in the US by Solomon and colleagues.1 The latest quality measures by the National Commission on Quality Assessment indicate that treatment for osteoporosis after a fracture in an older woman is merely 23%; thus, thousands of individuals are at an elevated risk for recurrent fractures. New quality indicators by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), namely Physician Quality Reporting System [48] (PQRS), are expected to promote clinical changes. PQRS measure 40, which addresses osteoporosis management after distal radius, vertebral, and hip fractures in women over the age of 50 years, will be used to assess performance for physicians. The Joint Commission is considering similar measures for hospitals. Quality improvement programs have been successful in increasing treatment rates for osteoporosis after a fracture, but as of yet, they are not widely available in the United States.2,3,4

Prevention of falls is another area with a gap in medical care. Falls are common in older individuals, affecting as many as 30% of older women. Injuries from falls include fractures and blunt head trauma, and may result in increased mortality. Women with self-reported osteoarthritis (OA), in particular, have an increased risk of falls and, in spite of elevated bone mass, remain at risk of fractures.5 In 2012, the cost of fall injuries totaled more than $36 billion. As the population ages, the financial toll for older-adult falls is projected to reach $59.6 billion by 2020.6

Falls result in more than 2.4 million injuries treated in ERs annually, including more than 772,000 hospitalizations and more than 21,700 deaths. Every 15 seconds, an older adult is treated in the ER for a fall. Every 29 minutes, an older adult dies after a fall.7

Musculoskeletal disorders are prevalent, and often of serious consequences in older adults. A greater awareness in the medical community and dissemination of effective interventions will result in a higher quality of life and prevention of disability among America’s seniors.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.2.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.2.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.3.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.3.csv

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.1.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.1.csv

[9] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.2.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.2.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.5.pdf

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.5.csv

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.6.pdf

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.6.csv

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.7.pdf

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.7.csv

[18] http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10028/exploring-the-biological-contributions-to-human-health-does-sex-matter

[19] http://www.nia.nih.gov/newsroom/features/nih-seeking-strategies-multiple-chronic-conditions-older-people

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.1.pdf

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.1.csv

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.2.1.pdf

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.2.1.csv

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.2.2.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.2.2.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.3.pdf

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.3.csv

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.1.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.1.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.2.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.2.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.3.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.4.3.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.5.pdf

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.5.csv

[36] http://www.agingsociety.org/agingsociety/publications/chronic/index.html

[37] http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/adulthipfx.html

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.1.pdf

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.1.csv

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.2.pdf

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.2.csv

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6A.2.2.2.pdf

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6A.2.2.2.csv

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.3.pdf

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.6.3.csv

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.7.pdf

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9B.7.csv

[48] http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html?redirect=/PQRS/

[49] http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/falls-prevention-in-older-adults-counseling-and-preventive-medication

[50] http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/Falls/community_preventfalls.html