An estimated 30 million children and adolescents participate in organized sports. In addition, some 150 million adults participate in physical activity that is not related to their employment. However, both of these large at-risk populations lack a mechanism for tracking injuries.

While professional and collegiate athletics have epidemiologic systems in place to track injury patterns, recreational athletics lack any type of surveillance system. However, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission has established the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System [1] (NEISS) in 1997 to track emergency room visits and injury patterns associated with specific products. This database has also been helpful as a means of documenting injuries associated with athletic endeavors.

Using the data, a 2002 CDC report detailed 4.3 million sports- and recreation-related injuries that were treated in US Eds.1 Injury rate was highest for boys aged 10 to 14 years. A more recent paper documented an estimated 600,000 knee injuries annually in EDs in the United States. Of these, 49.3% resulted from sports and recreation activities.2

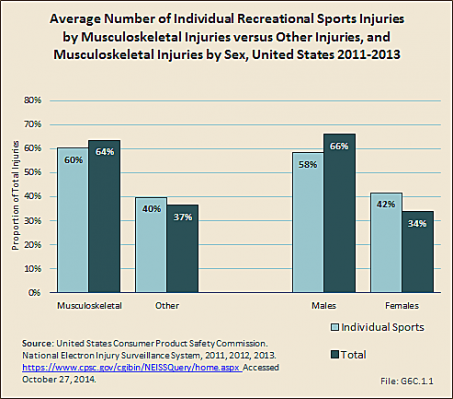

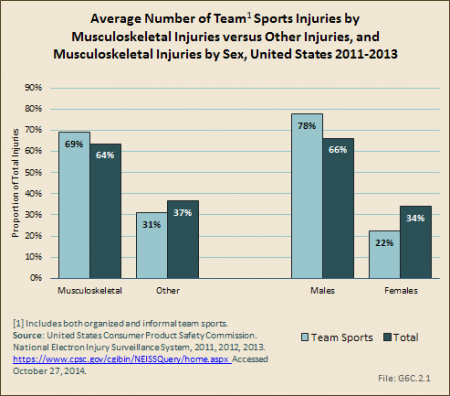

An estimated 2.8 million injuries resulting from individual sports are reported annually in EDs in the United States, of which 64% are musculoskeletal. Two out of three musculoskeletal injuries occur in males, with the proportion slightly lower for individual sports than for team sports.

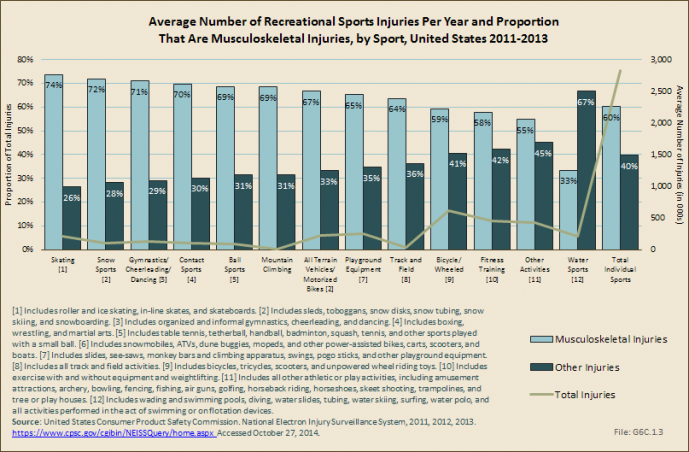

Cycling and wheeled sports account for 22% of all recreational sports injuries and musculoskeletal injuries serious enough to warrant a visit to the ED. Fitness training results in additional 16% of the total injuries and musculoskeletal injuries seen. Musculoskeletal injuries account for more than one-half of all injuries in all sports, with the exception of water sports. (Reference Table 6C.1 PDF [2] CSV [3])

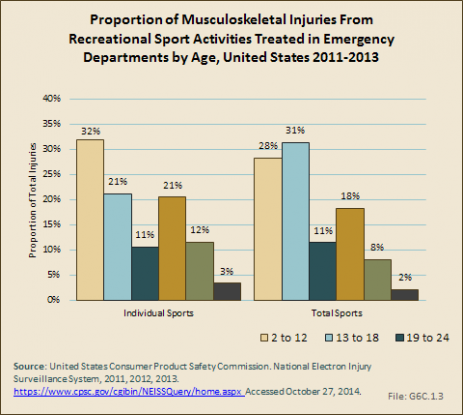

Musculoskeletal injuries treated in the ED as a result of a recreational sport injury occur in the highest proportion in children aged 2 to 12 years. This is in large part due to the high number of playground injuries, as well as biking and other wheeled equipment such as skate boards and scooters. Adults between the ages of 25 and 44 account for a substantial proportion of treated musculoskeletal injuries, but they also are a larger share of the population and more likely to be active in recreational sport activities. (Reference Table 6C.2 PDF [4] CSV [5])

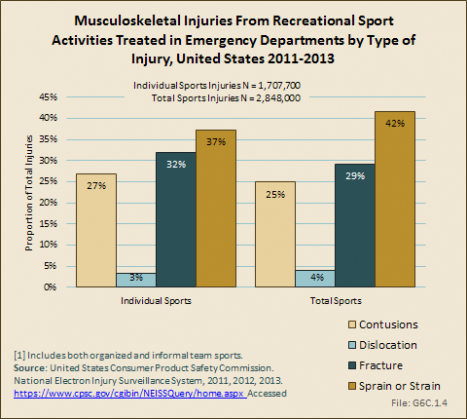

An estimated 37% of musculoskeletal injuries from athletic mechanisms result in sprains or strains, while fractures comprise 32% and contusions 27%. (Reference Table 6C.3 PDF [6] CSV [7])

Injuries to the extremities are the most common, with 41% occurring in the upper extremity, compared with 34% in the lower extremity. The trunk sustains most of the remaining injuries, with less than 7% involving the head. (Reference Table 6C.4 PDF [8] CSV [9]; Table 6C.7 PDF [10] CSV [11])

Nearly all sports injuries seen in the ED are treated and released to home. Fewer than 4% of recreational sports injuries result in hospitalization. Injuries from all-terrain vehicles and motorized bikes result in the highest hospitalization rate (7%) among individual sports, followed by 5% for injuries from nonmotorized wheeled activities (bicycles, skateboards, scooters, etc.). About 1 in 25 playground injuries results in hospitalization. (Reference Table 6C.5 PDF [12] CSV [13])

Scholastic sports has seen an 80% increase in participation between 1971 and 2005. These high school athletes experience an estimated 2,000,000 injuries, 500,000 doctor visits, and 30,000 hospitalizations per year.

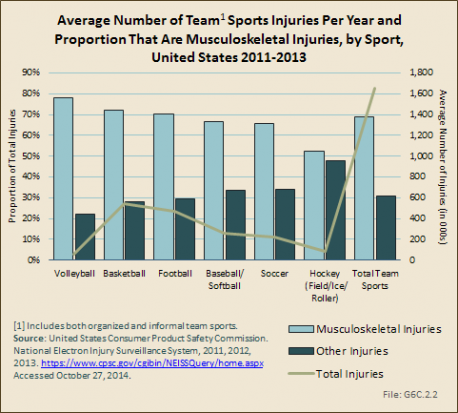

Using the NEISS dataset, more than 1.6 million injuries occurring as the result of team sports were reported in EDs in the United States annually in the three years studied. Musculoskeletal injuries comprised 69% of team sport injuries seen in the ED. The team sports causing the most injuries are basketball and football, which comprise 33% and 28%, respectively, of all injuries seen. (Reference T6C.1 PDF [2] CSV [3])

Volleyball has the highest proportion of musculoskeletal injuries among the team sports, but accounts for a small number of total injuries. Hockey sports injuries, including field, ice, and roller hockey, are split about evenly between musculoskeletal injuries and other types of injuries. (Reference T6C.1 PDF [2] CSV [3])

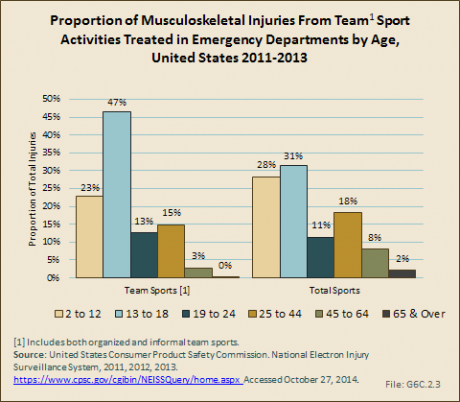

Musculoskeletal injuries seen in emergency departments occur most frequently (47%) within team sports in children between the ages of 13 and 18 years, the age at which many are participating in Little League and high school sports. Injuries from volleyball are more likely in this age group than other sports, but all team sports show about one-half of injuries seen in the ED within this age group. (Reference T6C.2 PDF [4] CSV [5])

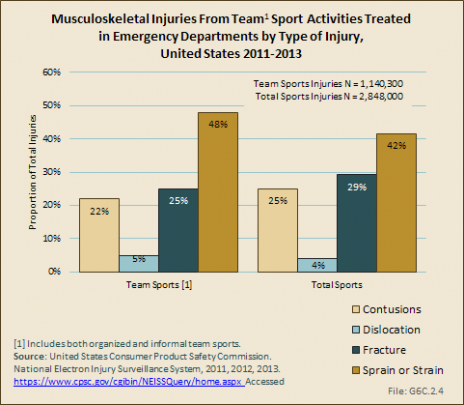

Nearly one-half (48%) of musculoskeletal injuries occurring while participating in team sports result in sprains or strains. Fractures occur in one in four injuries (25%), while contusions result in 22% of cases. (Reference Table 6C.3 PDF [4] CSV [7])

The majority of team injuries (84%) occur to the extremities. (Reference Table 6C.4 PDF [8] CSV [9]) Only 1% of team sport injuries results in hospitalization, with soccer injuries the most likely a cause for hospitalization (1.6%). (Reference Table 6C.5 PDF [12] CSV [13])

Another dataset created in 2004 to track scholastic sports injuries, the Reporting Information Online [14] (RIOTM), also provides quality epidemiologic information entered by athletic trainers associated with participating schools. Data from the 2005–2006 academic year suggests that injuries resulting from competition were 2.7 times higher than from practice, with boys’ football having the highest injury rates, both in practice as well as games.1

While less data on long-term health impact is available on scholastic athletes, one such study by McLeod and colleagues offers insight into the significant impact of athletic injury in this large population.2 They studied a convenience sample of 160 uninjured and 45 injured scholastic athletes with health-related quality-of-life measures. They found significantly lower scores among the injured athletes for the following subscores of the Quality of Life Short Form Questionnaire (SF-36)3: physical functioning, limitations due to health problems, bodily pain, social functioning, and the physical composite score. These findings suggest that physical injuries in our young athletes affect not only their physical function and risk for future musculoskeletal disability, but also extend beyond the physical aspects of overall health.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association [15] (NCAA)1 is comprised of nearly 1,100 member schools that compete in three division levels. More than 375,000 student athletes participate in NCAA sports that offer national championships annually, and this number continues to grow.2 During the 2013–2014 academic year, the number of teams competing in NCAA championship sponsored sports reached an all-time high of 19,086.

While there are numerous benefits associated with participating in collegiate athletics, there is also an increased risk of injury associated with participating in many types of sports. These injuries primarily affect the musculoskeletal system in general, and the lower and upper extremities specifically. Although awareness of risk of injury associated with participating in collegiate athletics is growing, there is little known about the long-term impact of injuries sustained while participating in collegiate athletics. Recent injury data from the NCAA Injury Surveillance System [16], as well as reports for specific joint injuries sustained by NCAA athletes and emerging data on the potential long-term impact of these injuries on health-related quality of life is presented.

For more than 30 years the NCAA, and since 2009 the Datalys Center [17], have been engaged in active injury surveillance within the unique population of college athletes. The collaborative effort between the NCAA and the National Athletic Trainers’ Association [18] (NATA) has yielded rich injury surveillance data used to develop important rule changes to protect player safety.3 In a 2007 special issue of The Journal of Athletic Training, data from the NCAA injury surveillance system from the 1988–1989 academic year through the 2003–2004 academic year were reviewed for 15 collegiate sports.4 With permission from the publisher, data from this study is included in this site. To read the full article, click here [19].

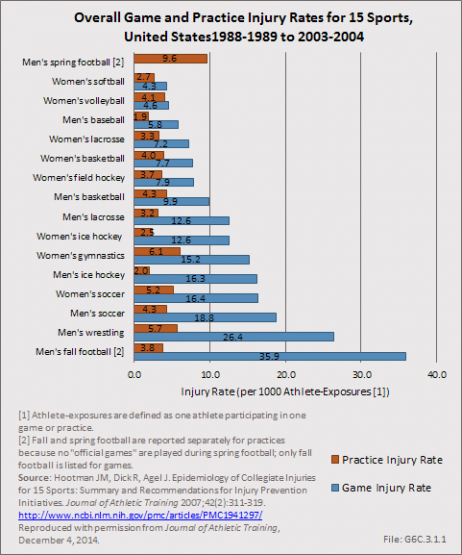

The 15 sports examined included five fall sports (men’s football, women’s field hockey, men’s soccer, women’s soccer, and women’s volleyball), six winter sports (men’s basketball, women’s basketball, women’s gymnastics, men’s gymnastics, men’s ice hockey, and men’s wrestling), and five spring sports (men’s baseball, men’s football, women’s softball, men’s lacrosse, and women’s lacrosse). Data for men’s spring football were only included in the analysis of practice injuries. These data provide insight into the burden of musculoskeletal injury experienced by collegiate athletes.

Hootman et al4 provided an overall summary of the NCAA data from the years 1988–1989 through 2003–2004, and made recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. Some of these data are highlighted in this section. CDC, which estimates 2.6 million children ages 0 through 19 years are treated in EDs each year for sports- and recreation-related injuries5, provides tips on how to prevent sports-related injuries in their Protect the Ones You Love Initiative [20].

Overall, incidence rates for the 15 sports examined range from a high of 35.9 per 1,000 game athlete exposures for men’s football to a low of 1.9 for men’s practice basketball. Among men, the highest injury rates were observed in football, wrestling, soccer, and ice hockey. Among women, the highest injury rates were experienced in soccer, gymnastics, ice hockey, and field hockey. (Reference Table 6C.9 PDF [22] CSV [23])

When data for all 15 sports are combined, injury rates are significantly higher in games (13.8 injuries per 1,000 athlete exposures) when compared to practice (4.0 injuries per 1,000 athlete exposures). Pre-season practice injury rates were significantly higher when compared to in-season or post-season training sessions. (Reference Table 6C.8 PDF [24] CSV [25])

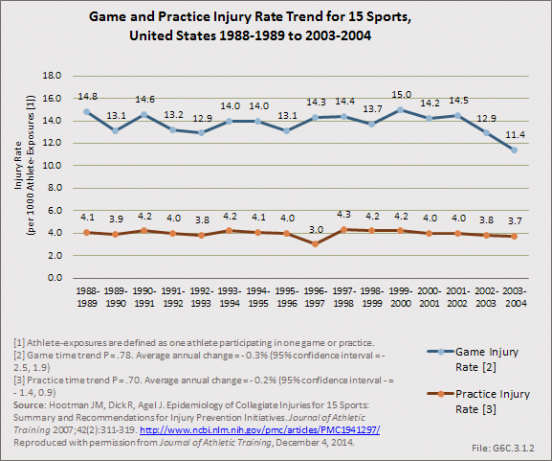

Combined injury rates for all 15 NCAA sports studied remained relatively stable over time. No significant changes were observed in injury rates during games or practices over the 16-year study period. (Reference Table 6C.10 PDF [26] CSV [27])

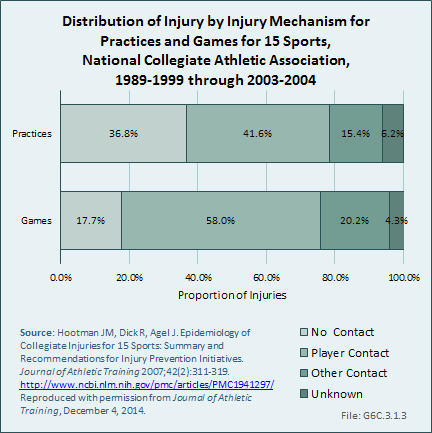

The majority of injuries resulted from contact with another player, regardless of whether or not injuries were sustained in practices or games. (Reference Table 6C.11 PDF [28] CSV [29])

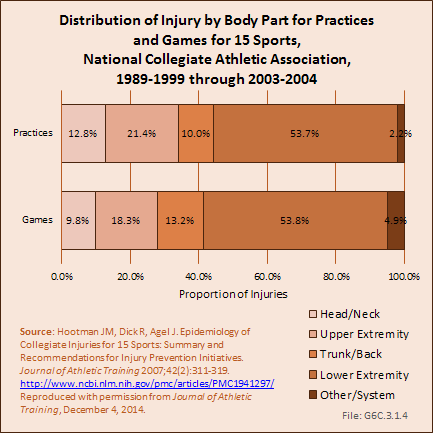

The majority of injuries documented during the study period affected the musculoskeletal system, with 72% of all injuries in games and 75% of all injuries in practices affecting the extremities. Regardless of whether injuries occurred in practices or games, more than one-half of all injuries reported across the 15 sports examined during the study period were to the lower extremity. (Reference Table 6C.12 PDF [30] CSV [31])

The NCAA injury surveillance system has also been used to examine the incidence and injury patterns of specific injuries among collegiate athletes.1,2 These studies have primarily focused on those injuries that likely have the greatest burden in terms of time loss from sport, the need for surgical intervention, and the potential for long-term impact on health. Specifically, joint injuries have been a primary concern, as it is well documented that these injuries can lead to chronic instability and increase the risk of osteoarthritis and degenerative joint disease.

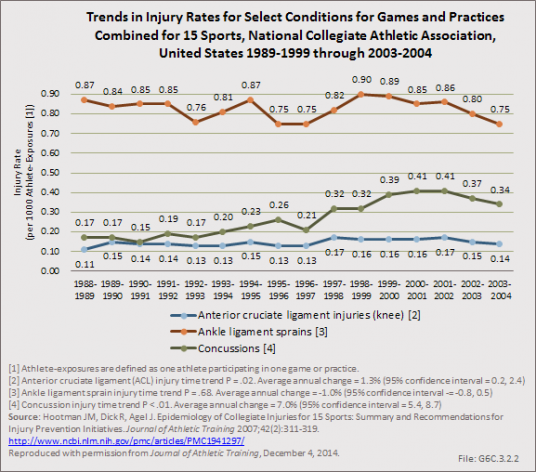

Acute traumatic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in the knee often lead to chronic pain and instability, and generally require surgical repair to restore function. There is also substantial evidence to suggest that acute traumatic knee joint injuries such as ACL tears significantly increase the risk for post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Several studies have focused on the rate of ACL injuries among collegiate athletes.1,3,4,5,6 Hootman et al6 estimated that approximately 2,000 athletes participating in 15 different men’s and women’s NCAA sports sustain an ACL tear annually. The average annual rate of ACL injury during the 16-year study period examined was 0.15 per 1,000 athlete-exposures. Arendt and Dick4 first reported that there were disparities in ACL injury incidence rates between males and females participating in the NCAA gender matched sports of soccer and basketball. This observation was confirmed in a follow-up study that examined data from 1990 through 2002.3 in male soccer players, Hootman et al6 reported that ACL injury rates among males and females combined, participating in 15 different NCAA sports, significantly increased during the 16-year study period. On average, they reported a 1.3% annual increase in the rate of ACL injury over time (P=0.02). (Reference Table 6C.14 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Dragoo et al7 compared ACL injury rates between NCAA football players participating on artificial turf and those participating on natural grass. They reported that the rate of ACL injury on artificial surfaces was significantly higher (1.39 times higher) than the injury rate on grass surfaces. They also noted that non-contact injuries occurred more frequently on artificial turf surfaces (44.29%) than on natural grass (36.12%).

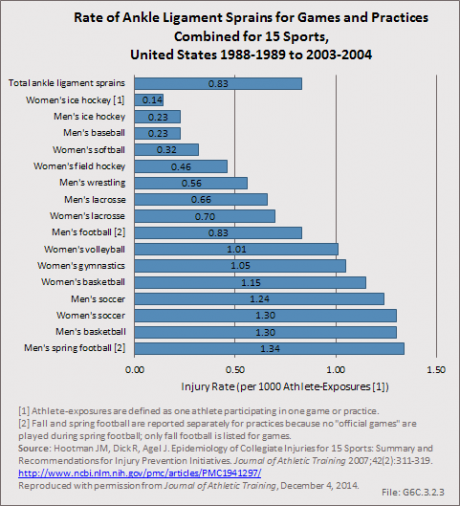

Ankle sprains are also common among NCAA athletes and they frequently lead to chronic pain, instability, and functional limitations. Hootman et al6 estimated that approximately 11,000 athletes participating in 15 different men’s and women’s NCAA sports sustain an ankle sprain annually. The average annual rate of ankle sprain injury during the 16-year study period examined was 0.86 per 1,000 athlete exposures. They also examined the annual injury rates for ankle sprains among males and females participating in these sports combined between 1988 and 2004 and reported that injury rates remained constant during the 16-year study period. On average, there was a nonsignificant 0.1% (P=0.68) annual decrease in the rate of ankle sprains during the study period. (Reference Table 6C.13 PDF [34] CSV [35])

Shoulder instability also impacts a significant number of NCAA athletes and can lead to chronic pain, recurrent instability, and functional limitations. Recurrent shoulder instability has also been associated with the increased risk of osteoarthritis in the shoulder. Surgical reconstruction is common following shoulder instability in young athletes. Owens et al2 examined the injury rates and patterns for shoulder instability among NCAA athletes over the 16-year period from 1988 through 2004 in the same 15 sports described previously. The overall injury rate for shoulder instability during the study period was 0.12 per 1,000 athlete exposures. On average, this is comparable to just under 2,000 shoulder instability events experienced annually in NCAA athletes. Injury rates for shoulder instability were significantly higher in games when compared to practice. Overall, NCAA athletes were 3.5 (95%CI: 3.29–3.73) times more likely to experience shoulder instability events in games when compared to practices. Just over half (53%) of the shoulder instability events documented during the study period were first-time instability events, with the remaining injuries being recurrent instability events (47%). The majority of shoulder instability events were due to contact with another athlete (68%) and other contact (20%). Nearly half (45%) of all shoulder instability events experienced by NCAA athletes during the study period resulted at least 10 days of lost playing time, with the remainder returning to play within 10 days of injury.

While we still have a rudimentary understanding of the impact that musculoskeletal injuries sustained by collegiate athletes have on long-term health outcomes, studies have recently begun to examine health related quality of life in current and former NCAA athletes. McAllister et al1 evaluated health-related quality of life in NCAA Division I athletes using the SF-36, and examined the association between scores and injury history and severity. Collegiate athletes who reported a history of mild injury had significantly lower physical component summary scale scores, role physical scores, bodily pain scores, social function scores, and general health scores on the SF-36 when compared to those with no history of injury. Collegiate athletes who reported a serious injury had significantly lower scores on all SF-36 component scores when compared athletes with no history of injury. Similar results were observed in a separate study that examined NCAA Division I and Division II athletes.2

More recently, studies have examined health-related quality of life in former NCAA athletes. Sorenson et al3 reported that former NCAA Division I athletes were significantly more likely to have joint-related health concerns when compared to non-athletes, and were 14 times more likely to seek professional treatment for their symptoms. They also reported that the prevalence of joint-related health concerns was significantly higher in older former athletes when compared to younger former athletes.

In a similar study, Simon et al4 examined health-related quality of life in former NCAA Division I athletes and former non-athletes using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).5 They reported that former collegiate athletes report significantly worse scores for five of the seven PROMIS scales examined when compared to non-athletes. Specifically, former athletes reported poorer scores on the physical function, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and pain interference scales. There were no differences noted between former NCAA athletes and non-athletes for the anxiety and satisfaction with participation in social roles scales. The authors also noted that former collegiate athletes reported significantly more major injuries, chronic injuries, daily limitations, and physical activity limitations when compared to non-athletes.

Overall, these studies suggest that NCAA athletes who sustain injuries during their college years have significantly lower health-related quality-of-life scores, and that these scores may get worse with time, particularly for join- related health issues and long-term major and chronic injuries. Decreased health-related quality of life in former college athletes may also contribute to greater daily activity and physical activity limitations when compared to non-athletes and may lead to significant chronic health comorbidities. Further research is needed to determine which factors contribute to the poorer health-related quality of life outcomes observed among former collegiate athletes in these studies.

Links:

[1] http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Safety-Education/Safety-Guides/General-Information/National-Electronic-Injury-Surveillance-System-NEISS/

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.1.pdf

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.1.csv

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.2.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.2.csv

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.3.pdf

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.3.csv

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.4.pdf

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.4.csv

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.7.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.7.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.5.pdf

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.5.csv

[14] https://highschool.riostudies.com/

[15] http://www.ncaa.org/

[16] http://www.datalyscenter.org/ncaa-injury-surveillance-program/

[17] http://datalyscenter.org/

[18] http://www.nata.org/

[19] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1941297/.

[20] http://www.cdc.gov/safechild/Sports_Injuries/index.html

[21] http://www.cdc.gov/safechild/index.html

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.9.pdf

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.9.csv

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.8.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.8.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.10.pdf

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.10.csv

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.11.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.11.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.12.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.12.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.14.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.14.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.13.pdf

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T6C.13.csv