Previous sections in this text clearly demonstrate the large percentage of health care visits that are attributable to musculoskeletal conditions. Most of the data used to establish these estimates concern adult patients. Unfortunately, there is significantly less information regarding the burden of these conditions in young patients.

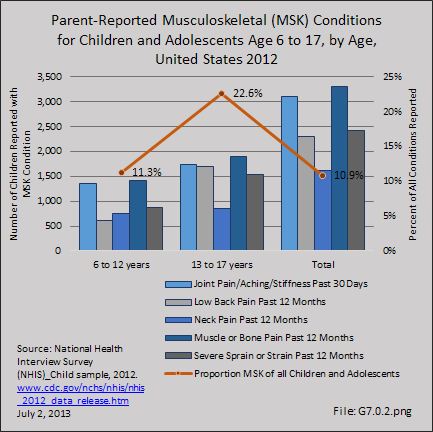

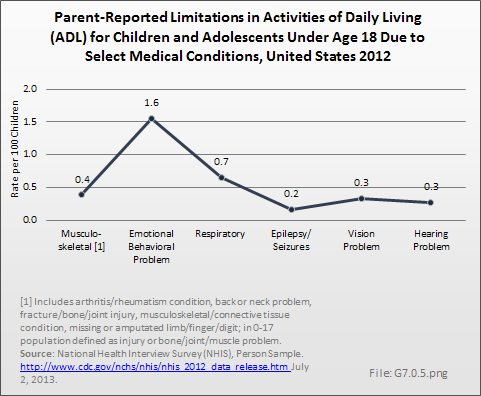

Studies, however, do support that pediatric musculoskeletal conditions similarly account for a significant portion of visits to medical providers. For instance, de Inocencio reported that greater than 6% of total visits to pediatric clinics were for musculoskeletal pain.1 Schwend reported that approximately one third of pediatric medical problems are related to the musculoskeletal system.2 In a population-based study in Ontario, Gunz reported that 1 in 10 children made a health care visit for a musculoskeletal problem and that 13.5% of all visits for musculoskeletal disease were made by patient’s age 0 to 19 years.3 Four in 1,000 children are reported by parents as having difficulty with activities of daily living due to musculoskeletal conditions. A search of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) child sample revealed that musculoskeletal conditions accounted for 10.9% of parent-reported health conditions for children and adolescents age 0 to 17 years in the US in 2012. This proportion was greatest at 22.6% in the 13- to 17-year-old age group. (Reference Table 7.0 PDF [1] CSV [2])

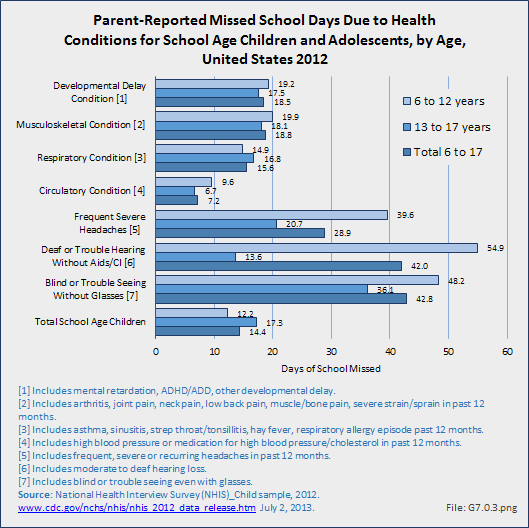

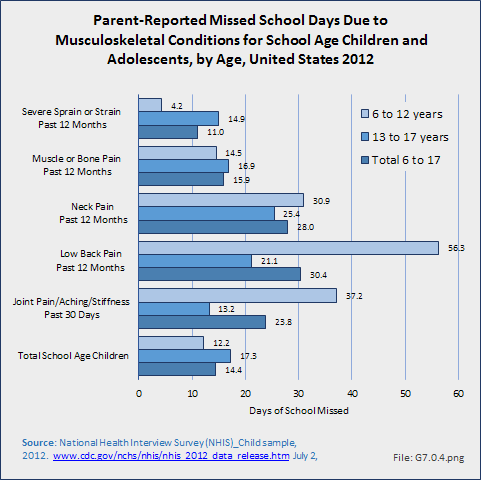

The evaluation and treatment of these pediatric musculoskeletal conditions resulted in approximately 149 million missed school days in 2012. Musculoskeletal conditions are surpassed only by respiratory infections as a cause of missed school days. Joint pain was the most frequent cause of missed school days, closely followed by low back pain. Missed school days due to musculoskeletal pain was higher for adolescents in the junior- and senior-high age range than for children of grammar-school age. (Reference Table 7.0.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

The indirect burden of pediatric musculoskeletal disorders is amplified by the effect on the family and caregivers. Each time a child visits a care provider for evaluation or treatment results in missed workdays and wages by parents and caregivers. Additionally, the emotional impact that many chronic musculoskeletal conditions have on the family is immeasurable. Furthermore, as compared to adult conditions, pediatric musculoskeletal conditions may have lifelong ramifications resulting in compounding burdens over time. (Reference Table 7.0.2 PDF [5] CSV [6])

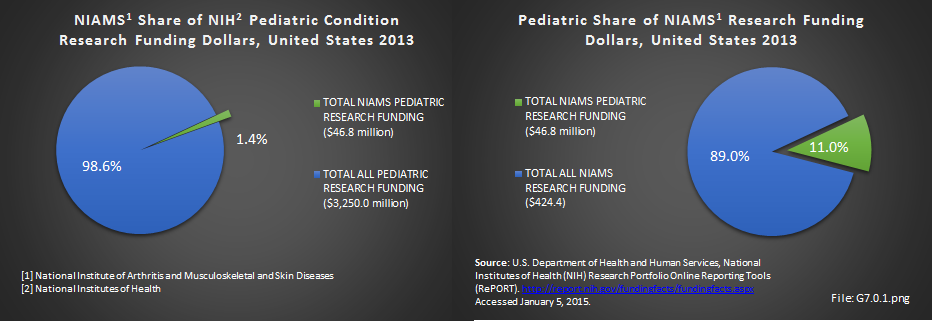

Despite the significant contribution made by musculoskeletal conditions in the total US health care burden, research for pediatric musculoskeletal conditions is grossly underfunded. Of the $3.25 billion in National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding for all pediatric conditions in 2013, only $46.8 million, or 1.4% of total pediatric medical research funding, went toward pediatric musculoskeletal research. Even under the umbrella of funding specifically for musculoskeletal research, pediatric-specific research is under-represented. Of the $424.4 million in funding for the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (NIAMS) in 2013, this same $46.8 million represented only 11% of total musculoskeletal research dollars.4

CONDITIONS

In order to perform a comprehensive review of the burden of musculoskeletal disease in children and adolescents, all conditions that either are direct musculoskeletal diagnoses or have musculoskeletal implications were considered for this section. This chapter was divided into separate clinically relevant sections to better understand the burden of each. These sections include musculoskeletal infections, deformity, trauma, neuromuscular conditions, syndromes with musculoskeletal implications, sports injuries, skeletal dysplasias, neoplasms, rheumatologic conditions, medical problems with musculoskeletal implications, and pain syndromes.

DATA

Health care visits and hospitalization data are derived from diagnostic codes for each of the conditions presented. These codes are available in the ICD-9-CM Codes [8] section of this topic. Total health care visits are the sum of cases seen in physicians’ offices, outpatient clinics, emergency departments, and hospital discharges. The largest database used is the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Kids’ Inpatient Database [9] (KID), which includes nearly 6.7 million weighted records of children and adolescents through the age of 20 years. All databases were analyzed for the ages 0 through 20 years, with subsets of data by age groups under 1 year, ages 1 through 5 years, 6 through 10 years, 11 through 13 years, 14 through 17 years, and 18 through 20 years.

Each database includes multiple variables to define diagnoses, ranging from three possible diagnoses in the physicians’ office and outpatient clinic data sets to 25 possible diagnoses in the KID database. If a diagnosis code is listed in any of the possible diagnoses variables, the record is coded as presenting with that condition. If the diagnosis code is listed in the first diagnosis variable, it is coded as the primary diagnosis. However, the databases do not permit diagnostic verification. The first diagnosis listed may not be the primary reason for the visit, but a contributing cause. Further, there is the potential for overlap in diagnosis of related conditions. Finally, sometimes diagnoses are provided primarily for reimbursement purposes, with little emphasis on accuracy. Therefore, these numbers provide only a guide to the impact of major childhood musculoskeletal conditions.

Injuries include two categories: sports injuries and all injuries due to a traumatic event. Sports injuries are identified by type of sports activity using the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System [10] (NEISS), with annual injuries averaged across the years of 2011 to 2013. Because sports injuries cases are not analyzed by ICD-9-CM codes, they may duplicate trauma injury cases.

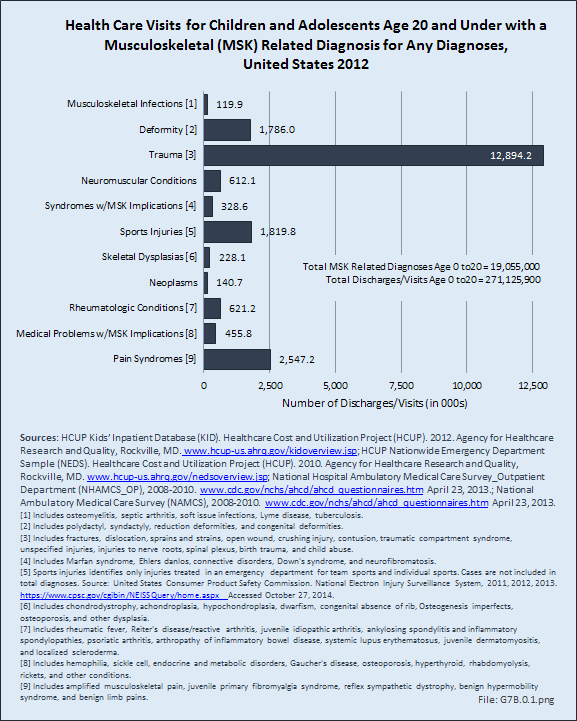

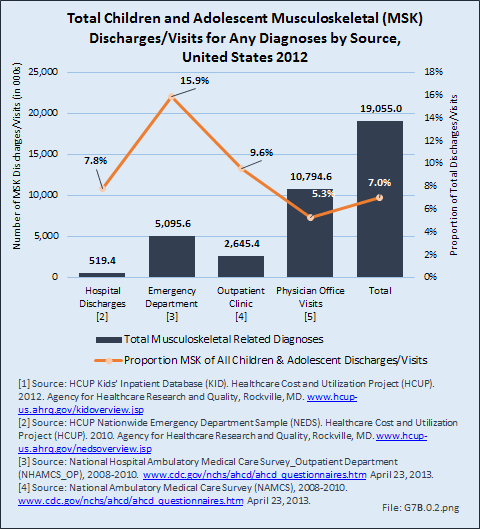

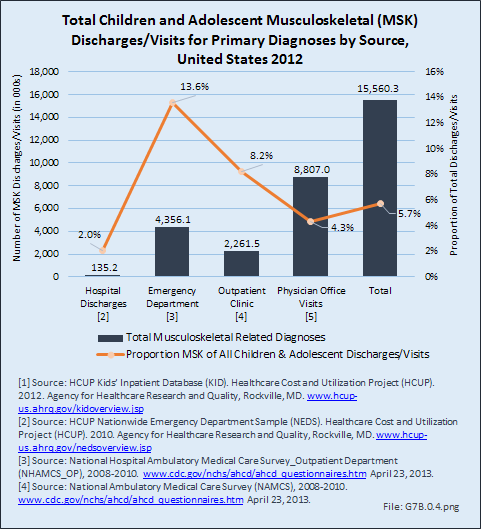

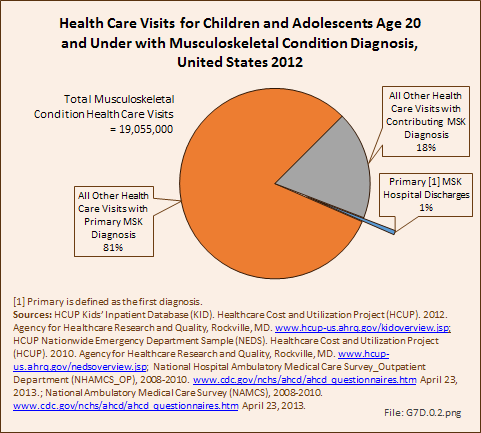

In 2012, more than 19 million children and adolescents age 20 years and younger received treatment in medical centers, physicians’ office, and hospitals for a condition that included a musculoskeletal related condition. More than two in three visits/discharges (68%) were for the treatment of traumatic injuries, a number that excludes sports injuries not based on diagnosis codes and likely already included in traumatic injuries. The second most common diagnosis is a pain syndrome, accounting for more than 1 in 10 visits (13%). Pain syndromes include amplified musculoskeletal pain, juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, benign hypermobility syndrome, and benign limb pains. The third most frequent diagnosis is deformity, accounting for just over 9% of all visits. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12])

More than one-half (57%) of visits by children and adolescents for a condition that included a musculoskeletal-related condition were to physicians’ offices. Hospital discharges accounted for less than 3% of total visits. Health care visits that included a musculoskeletal-related condition represented 7% of visits made by children and adolescents for any reason, but were nearly 16% of all visits to the emergency department. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12])

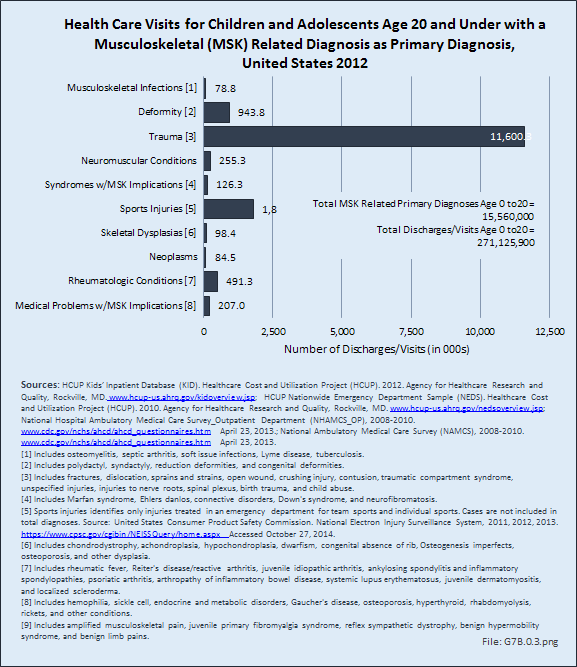

Of the 19 million health care visits by children and adolescents in 2012, 15.6 million had a primary diagnosis of a musculoskeletal-related condition. The greater proportion (75%) were for the treatment of traumatic injuries, again excluding sports injuries. The second and third most common primary diagnosis remained a pain syndrome (11%) and deformity (6%). Although other musculoskeletal related conditions accounted for 3% or fewer of total health care visits for a musculoskeletal-related condition, they nevertheless remain serious health concerns for children and adolescents. (Reference Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Again, the majority of visits were to physicians’ offices (57%), while visits to an emergency department with a primary musculoskeletal-related condition diagnosis accounted for 28% of visits. Hospital discharges accounted for less than 1% of total visits with a primary musculoskeletal diagnosis. Health care visits that included a primary diagnosis of a musculoskeletal-related condition represented 6% of visits made by children and adolescents for any reason, but were 14% of all visits to the emergency department. (Reference Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

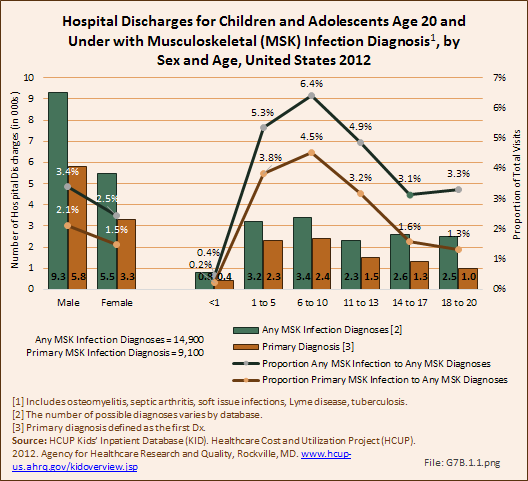

Musculoskeletal infections were diagnosed in 119,900 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 78,800 had a primary diagnosis of musculoskeletal infection. Of this total, 14,900 children and adolescents were hospital discharges, with 9,100 hospitalizations for a primary diagnosis of a musculoskeletal infection. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Males were more likely to be hospitalized with a musculoskeletal infection than females, as were children between the ages of 1 and 10 years. Musculoskeletal infections as a primary diagnosis accounted for 1.8% of hospital discharges for any musculoskeletal-related condition, but only 0.1% of hospital discharges for all health care reasons for children and adolescents age 20 years and younger. (Reference Table 7.2 PDF [15] CSV [16])

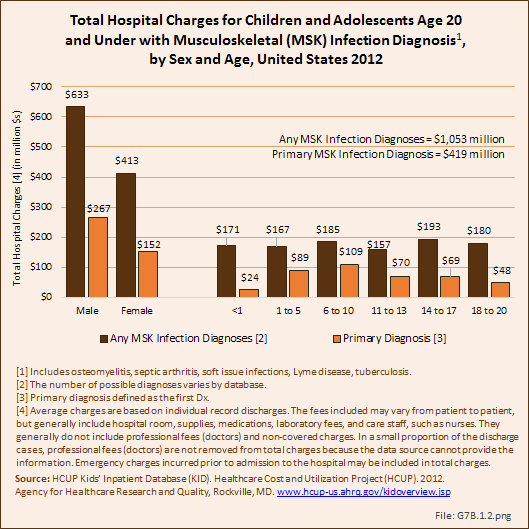

Total charges averaged $70,700 for a mean 8.5-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal infection along with other medical conditions. With a primary diagnosis of infection, the stay was shorter (6.3 days), and mean charges were $46,000. Total hospital charges for all primary musculoskeletal infection discharges in 2012 were $419 million. (Reference Table 7.2 PDF [15] CSV [16])

Deformity in children and adolescents was subdivided into five sections: upper extremity, lower extremity, hip and pelvis, spine, and other/unspecified.

Upper extremity deformity includes diagnoses such as polydactyly, syndactyly, reduction deformities such as amelia and longitudinal deficiencies of the upper extremity, and other congenital deformities such as synostosis, Madelung deformity, and Apert syndrome. A complete listing of deformity codes can be found by in the ICD-9-CM Child and Adolescents Codes [8].

Lower extremity deformity includes diagnoses such as polydactyly, syndactyly, reduction deformities such as amelia and longitudinal deficiencies of the lower extremity, genu varum, genu valgum, and other congenital developmental deformities such as clubfoot and flatfoot.

Hip and pelvis deformity includes diagnoses such as coxa valga, coxa vara, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, pelvic deformity, Legg Calves Perthes disease, and developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Spine deformity includes anomalies of the spinal cord such as syringomyelia and diastomatomyelia, as well as deformities of the vertebral column such as scoliosis, kyphosis, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and congenital spinal anomalies.

Other and unspecified deformities include deformities of the chest wall such as pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum, as well as nonspecific deformity diagnoses.

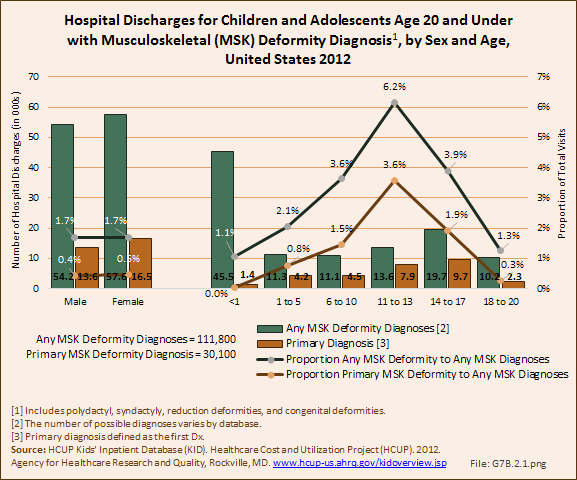

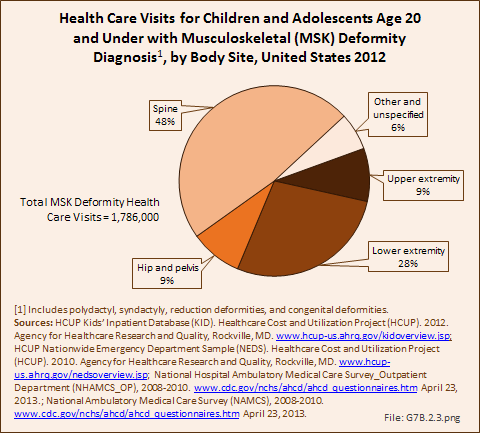

Musculoskeletal deformities were diagnosed in 1.8 million children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 943,800 had a primary diagnosis of musculoskeletal deformity. Among the total with any diagnoses of deformity, 111,800 children and adolescents were hospital discharges, with 30,100 hospitalizations for a primary diagnosis of a musculoskeletal infection. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

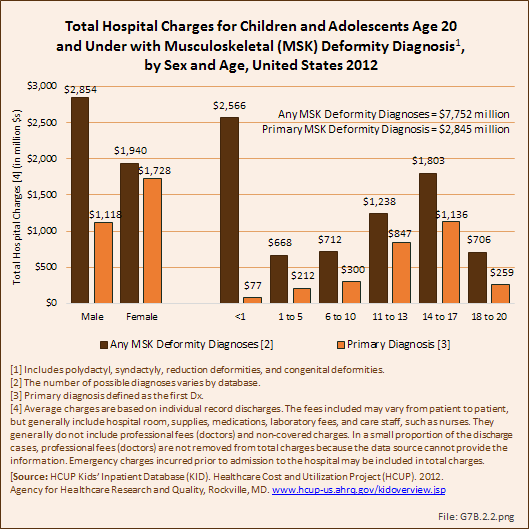

Females had a slightly higher rate of overall deformity diagnoses with hospitalization, and accounted for 55% of primary diagnosis hospitalizations. Children under the age of 1 year had a high rate of musculoskeletal deformity for any diagnosis with hospitalization (41%), but accounted for only 5% of primary hospitalizations. Primary diagnosis of musculoskeletal deformity with hospitalization increased with age.

Musculoskeletal deformity as a primary diagnosis accounted for 6% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, but only 0.5% of hospitalizations for any health care reasons for children and adolescents age 20 years and under. (Reference Table 7.3 PDF [17] CSV [18])

Deformity of the spine represented the largest share of hospitalizations (42%), followed by the lower extremity at 29% and upper extremity at 18%.

Total charges averaged $69,300 for a mean 6.4-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal deformity along with other medical conditions. With a primary diagnosis of deformity, the stay was shorter (4.1 days), but mean charges were much higher at $94,500, primarily due to the higher charges for children and adolescents age 11 years and older. Total hospital charges for all primary musculoskeletal deformity discharges in 2012 were $2.84 billion. (Reference Table 7.3 PDF [17] CSV [18])

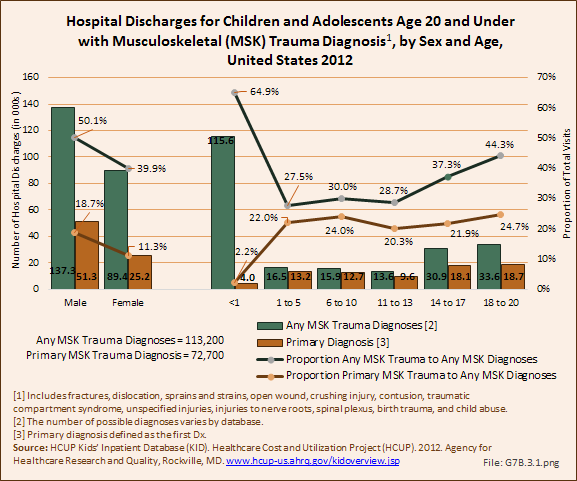

Trauma resulting in musculoskeletal injury was diagnosed in 12.9 million children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 90% (11.6 million) had a primary diagnosis of musculoskeletal injury. Only a small number were serious enough to require hospitalization. Among any trauma musculoskeletal injury diagnoses, 226,700 children and adolescents were hospitalized, with 76,600 hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of a musculoskeletal injury. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Males had nearly double the injury rates with hospitalization of females for both any diagnoses or as a primary diagnosis. Hospitalization for musculoskeletal injuries were greater between the ages of 1 and 10 years than for the middle ages of 11 to 13 years. However, they were highest for the oldest adolescents, age 14 years and older. Children under the age of one year had a high rate of musculoskeletal injury for any diagnosis with hospitalization, primarily due to a diagnosis of birth trauma, and reflected in the much lower rate of hospitalization with a primary trauma diagnosis.

Musculoskeletal injury as a primary diagnosis accounted for 15% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 1.1% of hospitalizations for any health care reasons for children and adolescents age 20 years and younger. For all but the youngest age (under 1 year), which is skewed by birth trauma, trauma accounted for 20% to 25% of all hospitalization for any musculoskeletal diagnoses. (Reference Table 7.4 PDF [19] CSV [20])

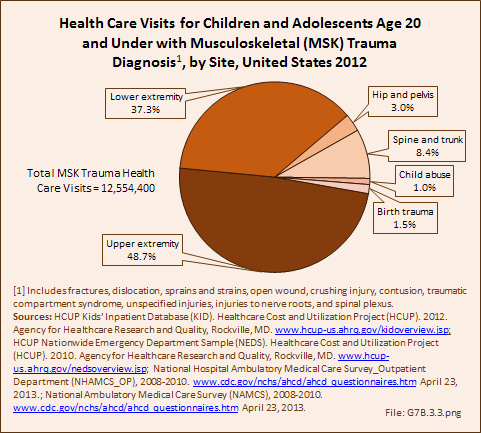

Trauma to the upper extremity account for nearly half (49%) of all trauma health care visits by children and adolescents. This was followed closely by lower extremity trauma (37%). Spine and trunk injuries were 8%, with hip and pelvis at 3%. Birth trauma was 1.5% of all health care visits, but accounted for nearly half (48%) of hospital discharges for musculoskeletal trauma diagnoses. Child abuse was reported in 1% of all health care visits for trauma. Trauma to multiple sites was cited in about 2% of cases. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12])

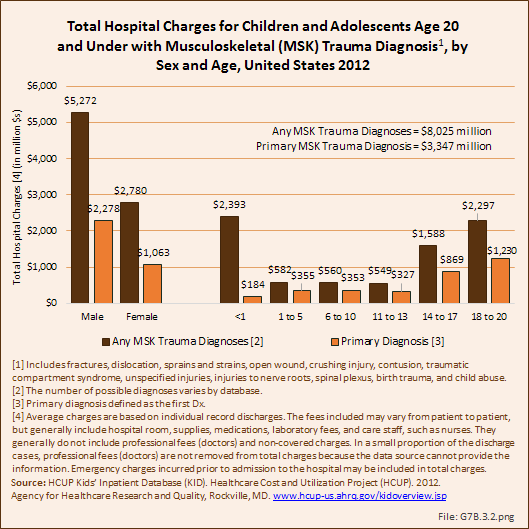

Total charges averaged $35,400 for a mean 4.2-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal injury along with other medical conditions. With a primary diagnosis of injury, the stay was shorter (3.2 days), but mean charges were higher at $43,700, likely due to the high number of birth trauma cases. Mean charges were highest for adolescents of high school age or older (14 to 20 years). Total hospital charges for all primary musculoskeletal injury discharges in 2012 were $3.35 billion. (Reference Table 7.4 PDF [19] CSV [20])

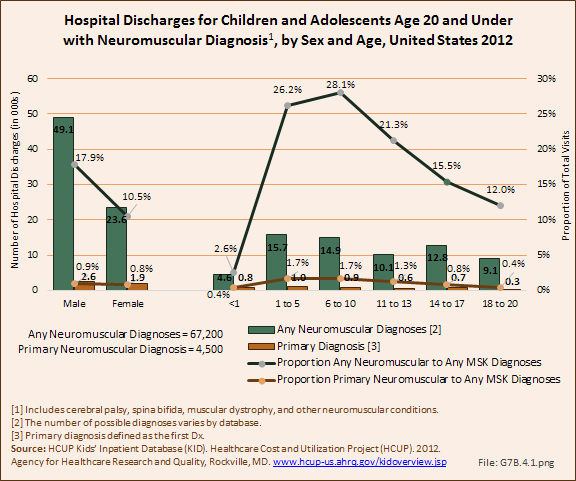

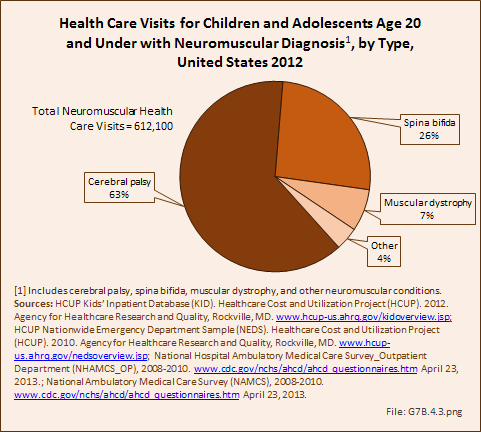

Neuromuscular conditions were diagnosed in 612,100 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 255,300 had a primary diagnosis of a neuromuscular condition. About 1 in 10 (11%) children and adolescents with any neuromuscular diagnoses were hospitalized (67,200), but fewer than 2% (4,500) with a primary neuromuscular diagnosis had a hospital discharge. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Males were more likely to be hospitalized than females for both any neuromuscular diagnoses or as a primary diagnosis. Children ages 6 to 10 years had the highest rate of hospitalization, both with any diagnoses and as a primary diagnosis. Rates of hospitalization declined as children age.

Neuromuscular conditions as a primary diagnosis accounted for about 1.5% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis and only 0.1% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. (Reference Table 7.5 PDF [21] CSV [22])

Cerebral palsy was diagnosed in two-thirds (66%) of hospital discharges. Spina bifida and muscular dystrophy represented 18% and 8% of discharges, respectively.

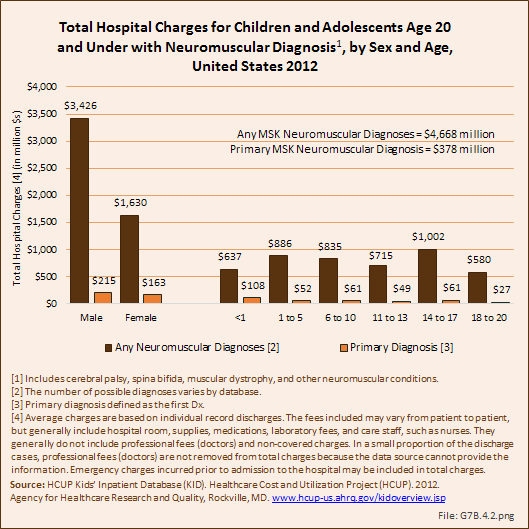

Total charges averaged $69,500 for a mean 6.7-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with a diagnosis of a neuromuscular condition along with other medical conditions. With a primary neuromuscular diagnosis, the stay was longer (7.5 days), and mean charges were higher at $84,000. Mean charges and length of stay were highest for the youngest patients, those under 1 year of age. Total hospital charges for all primary neuromuscular discharges in 2012 were $378 million. (Reference Table 7.5 PDF [21] CSV [22])

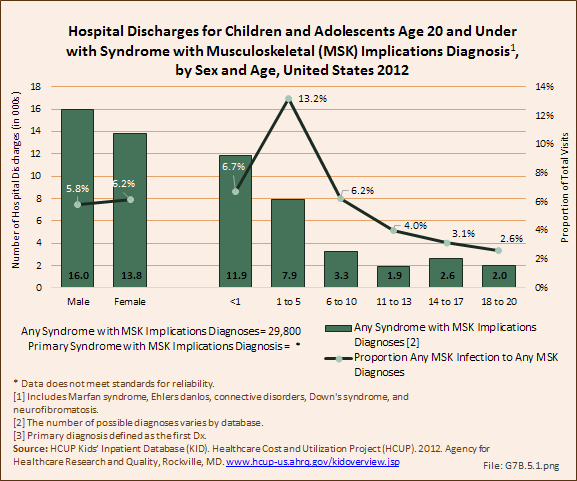

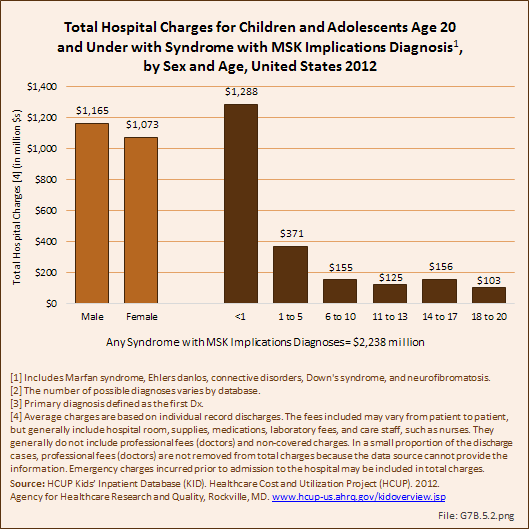

Syndromes with musculoskeletal implications were diagnosed in 328,600 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 126,300 had a primary diagnosis of a syndrome condition. About 1 in 10 (9%) children and adolescents with any syndrome with musculoskeletal implications diagnoses were hospitalized (29,800), but less than 1% (600) with a primary diagnosis of a syndrome with musculoskeletal implications had a hospital discharge. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Males, more than females, had a hospital discharge with any syndrome with musculoskeletal implications diagnoses. Infants and young children under the age of 5 years had the highest rate of hospitalization for any diagnoses of syndromes with musculoskeletal implications. The number of hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis was too small for analysis by sex and age.

Any diagnoses of syndromes with musculoskeletal implications accounted for 6% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 0.4% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis were 0.1% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses. (Reference Table 7.6 PDF [23] CSV [24])

Total charges averaged $75,100 for a mean 8.1-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with a diagnosis of a syndrome with musculoskeletal implications condition along with other medical conditions. With a primary syndrome diagnosis, the stay was slightly longer (8.7 days), and mean charges were higher at $100,800. Mean charges and length of stay were highest for the youngest patients, those under 1 year of age. Total hospital charges for primary syndrome with musculoskeletal implications discharges in 2012 were $60.5 million. (Reference Table 7.6 PDF [23] CSV [24])

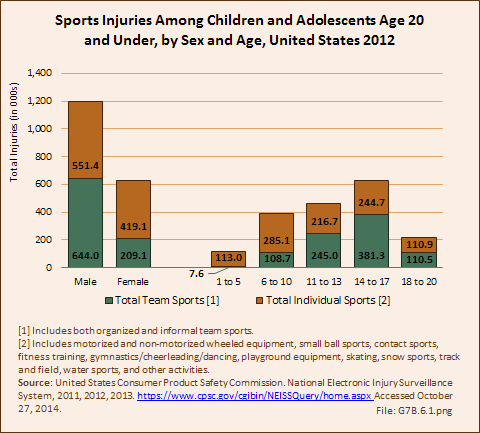

On average across the years from 2011 to 2013, 1.8 million injuries per year related to team or individual sport activities occurred to children and adolescents age 20 years and younger. Data reported is from consumer product-related injuries occurring in the United States from a statistically valid sample of emergency departments collected by the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Data shown for sports injuries are not included in the overall total for musculoskeletal conditions among children and adolescents, on the assumption it duplicates numbers found in the emergency department database based on ICD-9-CM codes and used in the trauma injuries [27] section.

Males report injuries at twice the number as females, with the highest number of injuries occurring in the junior high (11 to 13 years) and high school (14 to 17 years) ages. (Reference Table 7.7.1 PDF [28] CSV [29])

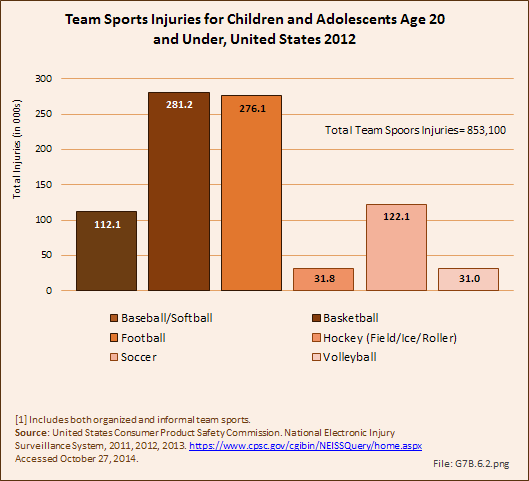

Team sports, both organized and informal, accounted for just under one-half (47%, or 853,100 injuries) of all sports-related injuries reported. Basketball had the highest number of team sport related injuries at 33%, and was closely followed by football at 32%.

Team sport injuries to males were three times the number reported for females. The only sport in which female injuries outnumber male injuries is volleyball. Nearly half (45%) of team sport injuries to children and adolescents occurred during the high school years (age 14 to 17 years), with another 28% in the junior-high age range of 11 to 13 years. (Reference Table 7.7.1 PDF [28] CSV [29])

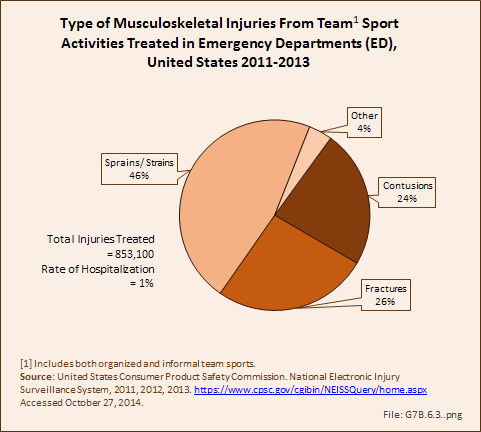

The most common musculoskeletal injury incurred was a sprain or strain, accounting for 46% of team sport injuries. Volleyball had the highest proportion of sprains and strains, followed by basketball. Baseball led in contusion injuries, while fractures occurred most frequently in football, hockey (including field, ice, and roller hockey), and soccer. (Reference Table 7.7.2 PDF [30] CSV [31])

Only 1% of team sport injuries were serious enough to result in hospitalization.

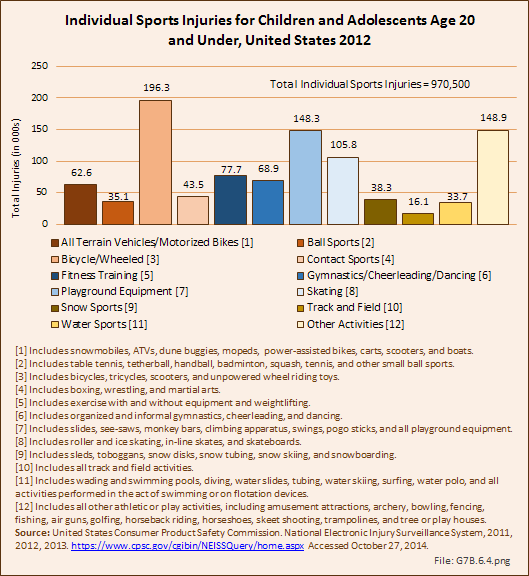

Individual sports injuries accounted for 53% of total injuries reported (970,500). One in five injuries occurred while riding bicycles or other nonmotorized wheeled equipment such as tricycles and scooters. These injuries occurred most frequently to children ages 6 to 10 years, but were common at all ages. Injuries on playground equipment were the second highest type of individual sport injuries, accounting for 15% of all injuries. Playground equipment injuries occurred almost exclusively to children age 10 years or younger. Skating injuries, which includes roller and ice skates, inline skates, and skateboards, were the cause of 11% of individual sport injuries.

Females accounted for a larger share of individual sport injuries (43%) than in team sports. Still, the only activity in which females had a significantly higher number of injuries than males was in gymnastics/cheerleading/dancing. (Reference Table 7.7.1 PDF [28] CSV [29])

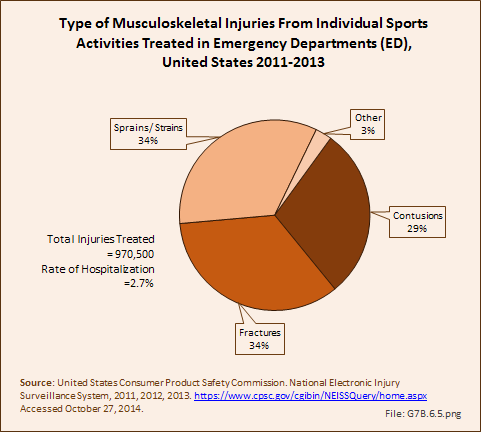

Fractures and sprains/strains each accounted for one-third of all individual sport activity injuries. However, the type of musculoskeletal injury varied substantially with the type of activity. Fractures resulted from playground equipment injuries one-half the time, and there were a higher share of fractures in snow sports and skating injuries as well. Sprains/strains occurred in two-thirds of track and field injuries, and there were a higher share of sprains/strains occurring in gymnastics/cheerleading/dancing and fitness training injury category as well. The most common type of injury reported from bicycle/wheeled equipment were contusions. (Reference Table 7.7.2 PDF [30] CSV [31])

Nearly 3% of individual sport injuries resulted in hospitalization.

Skeletal dysplasias, also referred to as osteochondrodysplasias, are a heterogeneous group of disorders that affect the growth and development of bone and cartilage. There is great variability of severity and involvement ranging from neonatal lethality to mild growth differences noted incidentally in adulthood. Hundreds of such dysplasias have been described but most are so rare that true incidence is difficult to estimate.1 The most common diagnoses included in this category are achondroplasia, hypochondroplasia, pseudoachondroplasia, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, diastrophic dysplasia, multiple hereditary exostosis, enchondromatosis, osteogenesis imperfecta, and osteopetrosis. The overall incidence of skeletal dysplasias is two to five per 10,000 live births.2 Despite their relative rarity, many patients with these disorders require extensive medical and surgical treatments throughout their childhood and into adulthood.

Because of the rarity of skeletal dysplasias, data on health care visits for these conditions is too small to be reported.

Pediatric musculoskeletal neoplasms are relatively rare. They can be categorized as either benign or malignant, as has been done for this document. Musculoskeletal neoplasms are often also categorized by the type of tissue they produce or from which they are derived.

The most common types of tumors that affect the musculoskeletal system by tissue type are cysts, bone-producing tumors, cartilage tumors, fibrous tumors, soft tissue tumors, and peripheral neuroectodermal tumors. Most benign tumors, such as nonossifying fibromas, result in little or no disability and require no treatment. Other benign tumors may require surgical intervention. Painful or prominent osteochondromas may require surgical excision. Simple bone cysts can weaken the bone and increase fracture risk, and may require surgery treatment in order to resolve the cyst and prevent fracture. Other benign tumors include lipomas, fibrous dysplasia, enchondromas, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastomas.

The most common malignant tumors of the pediatric musculoskeletal system are osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma/peripheral neuroectodermal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, and synovial cell sarcoma. Osteosarcoma is the most common malignant bone tumor in patients under 20 years of age, with an incidence of around 29 per 1 million people. Ewing sarcoma is the second most common pediatric malignant musculoskeletal tumor and is part of the Ewing family of tumors, which includes peripheral neuroectodermal tumors. Most of the tumors in the family have the genetic translocation.1 Long-term survival of patients with both of these tumors has drastically improved with the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy.

For additional information on musculoskeletal tumors in children you can refer to the Tumors [32] section of this report.

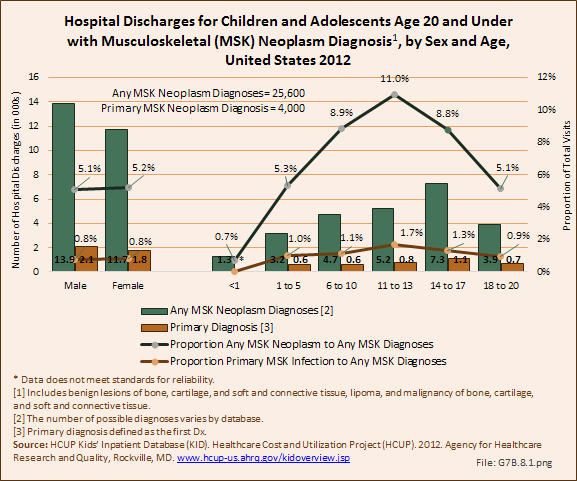

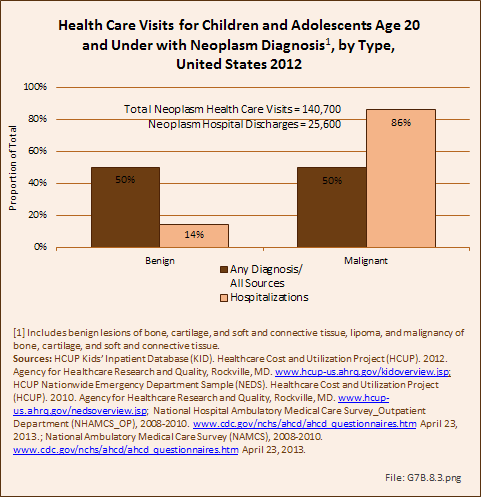

Neoplasms, including both benign and malignant, were diagnosed in 140,700 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 84,500 had a primary diagnosis of a neoplasm. About one in five (18%) of children and adolescents with any neoplasm diagnoses were hospitalized (25,600), but fewer than 5% (4,000) with a primary diagnosis of a neoplasm had a hospital discharge. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

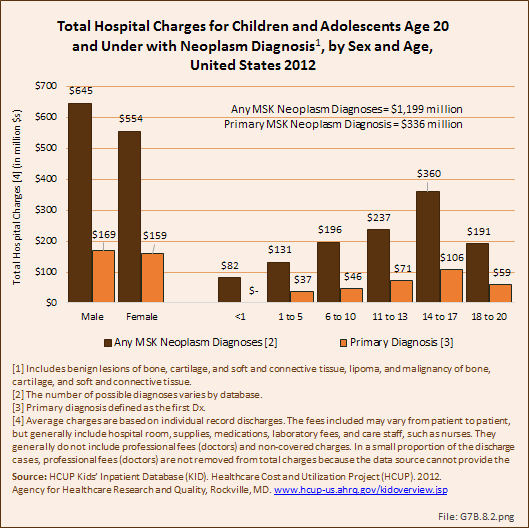

Slightly more males than females had a hospital discharge with any or a primary neoplasm diagnosis. As children age, there is a higher incidence of neoplasm prevalence resulting in hospitalization.

Any diagnoses of neoplasm accounted for 5% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 0.4% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of neoplasm were 0.8% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses and 0.1% of hospitalizations for any health condition diagnosis. (Reference Table 7.8 PDF [33] CSV [34])

Neoplasm diagnoses are divided equally between benign and malignant neoplasm for any diagnoses and all sources, but 86% of hospitalized diagnoses are malignant.

Total charges averaged $46,900 for a mean 4.6-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with any diagnosis of neoplasm along with other medical conditions. With a primary neoplasm diagnosis, the stay was slightly longer (6.2 days), and mean charges were higher at $84,100. Mean charges and length of stay were highest for children ages 14 to 17 years, but the increase rose steadily from the youngest patients. Total hospital charges for primary neoplasm diagnosis discharges in 2012 were $336.3 million. (Reference Table 7.8 PDF [33] CSV [34])

An estimated 300,000 children in the Unites States are diagnosed with juvenile arthritis or another chronic rheumatologic condition such as systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, or linear scleroderma.1 These chronic musculoskeletal conditions generally require chronic care, and without appropriate treatment can lead to significant disability.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (formally called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis [JRA] or juvenile chronic arthritis [JCA]) is estimated to affect 1 in 1,000 children in the United States.2 JIA is diagnosed in a child younger than 16 years of age with at least six weeks of persistent arthritis. There are seven distinct subtypes, each having a different presentation and association to autoimmunity and genetics.3 Certain subtypes are associated with an increased risk of inflammatory eye disease (uveitis). Understanding the differences in the various forms of JIA, their causes, and methods to better diagnose and treat these conditions in children is important to future treatment and prevention. Among all subtypes, approximately half of children with JIA still have active disease after 10 years.4

There are several other causes of acute or chronic arthritis in children that do not meet the diagnostic criteria of JIA, including, but not limited to, rheumatic fever, Reiter syndrome/reactive arthritis, and the arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

Approximately 15% to 20% of cases of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the United States occur in children younger than 18 years of age. SLE is a chronic autoimmune condition characterized by the production of autoantibodies leading to immune complex formation and end organ damage. For reasons that remain unclear, pediatric SLE is associated with increased disease severity, increased short- and long-term morbidity, and mortality as compared to adult-onset SLE.5

Juvenile dermatomyositis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by inflammation of the skin and muscle. Estimated incidence of the disease in the United States is 0.5 per 100,000 people; the prevalence is not known.2

The sclerodermatous conditions are defined in part by the common clinical feature of tightening or hardening of the skin. Systemic scleroderma, also called diffuse cutaneous systemic scleroderma, is rare in childhood, accounting for only 2% to 3% of all cases of this condition, which has an estimated prevalence of 24 cases per 100,000 people. Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of scleroderma diagnosed in the pediatric population. It is characterized by a linear streak of sclerosis typically involving an upper or lower extremity.2

In 2006, the CDC Arthritis Program finalized a case definition for ongoing surveillance of pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (SPARC) using the current ICD-9-CM diagnostically -based data systems.6 In response to the variations in conditions that some felt should be included but were not, CDC generated estimates not included in the case definition.

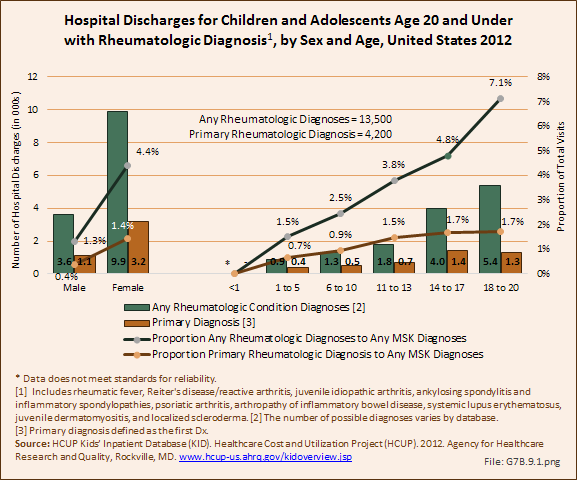

Using the SPARC definitions, rheumatologic conditions were diagnosed in 621,200 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 491,300 had a primary diagnosis of a rheumatologic condition. Only 2% of children and adolescents with any rheumatologic diagnoses were hospitalized (13,500), while less than 1% (4,200) with a primary diagnosis of a rheumatologic condition had a hospital discharge. The majority of children and adolescents with a rheumatologic condition diagnosis were seen in physicians’ offices. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12]; and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

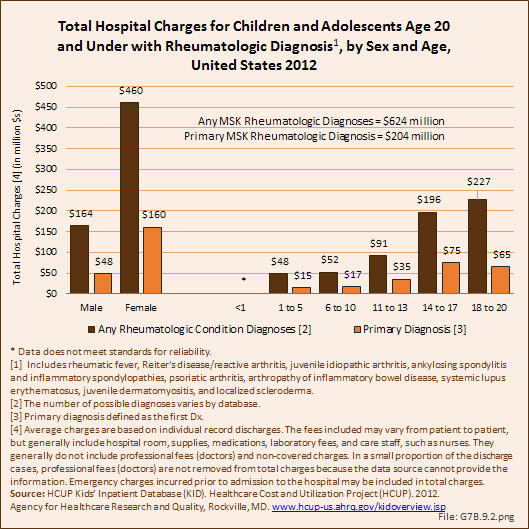

Females were hospitalized with a rheumatologic condition at nearly three times the rate of males, both for any diagnoses and as a primary diagnosis. As children age, there is a higher incidence of rheumatologic conditions diagnosis.

Any diagnoses of a rheumatologic condition accounted for just under 3% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 0.2% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of a rheumatologic condition were 0.8% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses and 0.1% of hospitalizations for any health condition diagnosis. (Reference Table 7.9 PDF [36] CSV [37])

Total charges averaged $46,200 for a mean 5.3-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with any diagnosis of a rheumatologic condition along with other medical conditions. With a primary rheumatologic diagnosis, the stay was about the same (5.1 days), and mean charges only slightly higher at $48,500. Age and sex were not significant factors in length of hospital stay and average charges for a rheumatologic condition diagnosis. Total hospital charges for primary rheumatologic condition diagnosis discharges in 2012 were $203.8 million. (Reference Table 7.9 PDF [36] CSV [37])

Many medical problems have musculoskeletal implications. This section discusses some of the more common of those diagnoses, including hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and endocrine and metabolic disorders such as rickets and lysosomal storage disorders.

Hemophilia is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal blood clotting secondary to congenital deficiency of clotting factors VIII and IX. It may result in musculoskeletal problems by way of hemophilic arthropathy and intramuscular hemorrhage. Hemophilic arthropathy occurs through spontaneous bleeding into a weight-bearing joint, resulting in cartilage degeneration and arthrosis as well as asymmetric growth stimulation and deformity.

Sickle cell disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and is characterized by production of abnormal hemoglobin. This results in reduced oxygen delivery to tissues and can lead to multiple musculoskeletal manifestations, including painful bone infarcts, osteomyelitis, avascular necrosis, and vertebral compression fractures.

Metabolic bone diseases, such as rickets, occur due to abnormal calcium and phosphate metabolism. Rickets occurs in many forms, including vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D resistance, hypophosphatemic rickets, and renal osteodystrophy. Regardless of the cause, the result is inadequate calcification of bone and cartilage, resulting in bone pain and deformity.

The most common lysosomal storage disease is Gaucher’s disease, an autosomal recessive condition characterized by a deficiency in the enzyme beta-glucocerebrosidase. In Gaucher’s disease, there is an accumulation of glucocerebrosides, which contain glucose, in the tissues. This results in musculoskeletal manifestations that include bone deformity secondary to bone marrow infiltration, avascular necrosis, bone pain, pathologic fracture, and osteomyelitis.

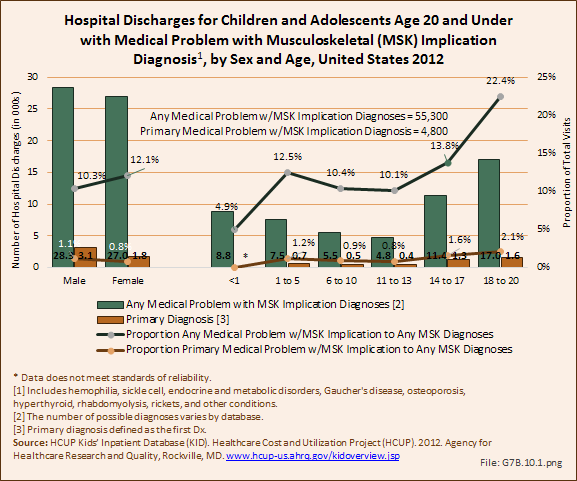

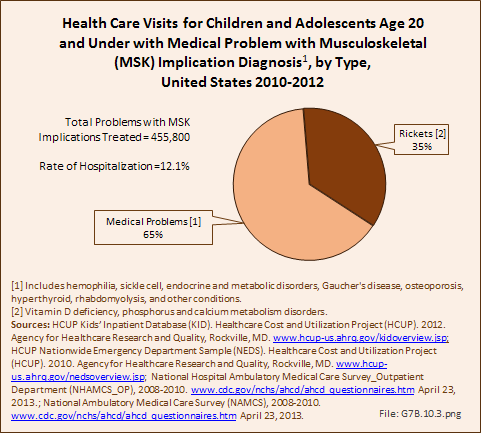

Medical problems with musculoskeletal implications were diagnosed in 455,800 children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 45% (207,000) had a primary diagnosis of a medical problem with musculoskeletal implications condition. More than one in ten (12%) children and adolescents with any medical problem diagnoses were hospitalized (55,300), while 2% (4,800) with a primary diagnosis had a hospital discharge. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Males and females were hospitalized with a medical problem with musculoskeletal implications in about the same numbers, but with a primary diagnosis, males were more likely to be hospitalized. The highest rate of hospitalization when compared to other MSK conditions, was for adolescents age 18 to 20 years of age, the ages just entering adulthood. However, this age group tends to have a higher rate of musculoskeletal hospitalizations overall.

Any diagnoses of a medical problem with musculoskeletal implications accounted for 11% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and less than 1% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of a medical problem were 1% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses and 0.1% of hospitalizations for any health condition diagnosis. (Reference Table 7.10 PDF [38] CSV [39])

Rickets accounted for 35% of all health care visits for medical problems with musculoskeletal implications, but 69% of the hospitalized cases. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12])

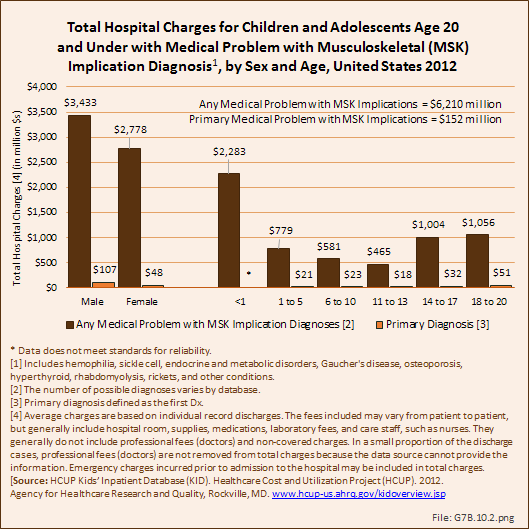

Total charges averaged $112,300 for a mean 11.5-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with any diagnosis of a medical problem with musculoskeletal implications along with other medical conditions. With a primary medical problem diagnosis, the stay was shorter (3.5 days), and mean charges about a fourth that of medical problems as a contributing condition ($31,600).

When hospitalized with any diagnosis of a medical problem with musculoskeletal implications along with other medical conditions, males had slightly longer hospital stays and charges than females did. Infants under the age of 1 year had significantly longer stays and higher charges than other age groups, primarily due to cases of rickets. However, for primary medical diagnoses of musculoskeletal implications along with another medical condition, sex and age were not major factors in length of hospital stay and mean charges. Total hospital charges for primary medical problem with musculoskeletal implications diagnosis discharges in 2012 were $151.7 million. (Reference Table 7.10 PDF [38] CSV [39])

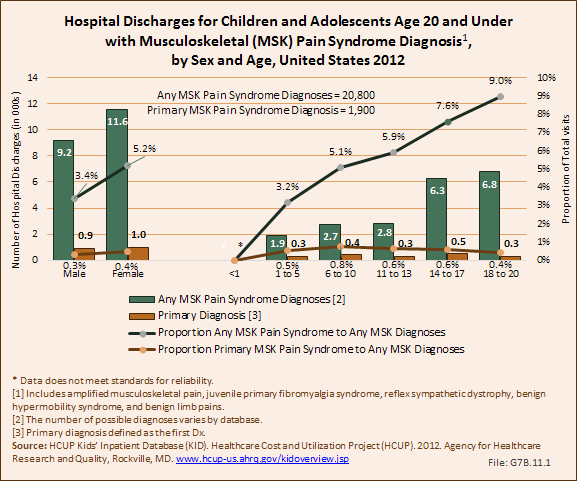

Musculoskeletal pain syndromes, including amplified musculoskeletal pain, juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, benign hypermobility, and benign limb pains, are common diagnoses in the pediatric population. A systematic review examining the prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain found a range of prevalence rates between 4% and 40% in children. Rates were generally higher in girls and increased with age.1 It is estimated that 5% to 8% of new patients presenting to North American pediatric rheumatologists have a musculoskeletal pain syndrome.2

Amplified musculoskeletal pain and juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome are related conditions with the common feature of diffuse pain involving at least three major body parts for at least 3 months. Patients also typically have sleep disturbance and other somatic complaints, such as headaches and abdominal pain. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), now also called complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), is a form of amplified pain in which autonomic dysfunction develops in an extremity, often following injury or trauma. The affected limb becomes swollen and discolored and the area can be very painful with light touch (allodynia). The recommended treatment for these conditions includes restoring normal sleep patterns, a therapy program with a focus on exercise and desensitization, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Some patients require treatment in an in-patient setting.3

Benign limb pains, also sometimes referred to as “growing pains,” are most common in children age 2 to 5 years. Children with benign limb pains tend to complain of pain at night, often awaking from sleep due to pain. These symptoms tend to resolve with age. Benign hypermobility is diagnosed in patients who have hypermobile joints4, without an underlying connective disuse disorder. This condition is common, affecting 8% to 20% of White populations. Anterior knee pain and back pain are more common in hypermobile vs nonhypermobile individuals.2

Pain syndromes were diagnosed in more than 2.5 million children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 66% (1.7 million) had a primary diagnosis of a pain syndrome. Less the 1% of children and adolescents with any pain syndrome diagnoses were hospitalized (20,800), while a tiny fraction (1,900) with a primary diagnosis had a hospital discharge. The majority of children and adolescents with a pain syndrome diagnosis were seen in physicians’ offices. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Females were hospitalized with a pain syndrome diagnosis in slightly higher numbers than males, both for any diagnoses and as a primary diagnosis. Pain syndrome diagnoses increase as a contributing diagnosis in older children, but as a primary diagnosis age is not a factor.

Any diagnoses of pain syndrome accounted for just over 4% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 0.3% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis pain syndrome were 0.4% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses and a tiny portion of hospitalizations for any health condition diagnosis. (Reference Table 7.11 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Total charges averaged $42,000 for a mean 5.6-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with any diagnosis of a pain syndrome along with other medical conditions. With a primary pain syndrome diagnosis, the stay was shorter (3.1 days), and mean charges about half that of pain syndrome as a contributing condition ($22,900). Age and sex were not significant factors in length of hospital stay and average charges for a medical problem diagnosis. Total hospital charges for primary pain syndrome diagnosis discharges in 2012 were $43.4 million. (Reference Table 7.11 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Conditions commonly thought of as only affecting children, such as cerebral palsy, osteogenesis imperfecta, spina bifida, and juvenile inflammatory arthritis, are now being seen more than ever in adults thanks to the tremendous progress in care leading to longer life expectancy. Remarkably, some people with Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy are now surviving into early adulthood. Concomitant with this success has come a host of new issues concerning the transition of care to adulthood and the aging process.

Adults with these conditions are disproportionately affected by the aging process. Some issues, such as mobility challenges making it difficult to participate in fitness regimens to prevent secondary conditions associated with sedentary lifestyles (e.g. obesity, diabetes and heart disease), are clear. Other issues are less clear. Adults with aftereffects of childhood musculoskeletal disorders have more difficulty accessing preventative care. Even more subtle, are issues related to lack of providers skilled in treating adults with the sequela of childhood issues and psychosocial challenges.

The medical community needs to investigate whether the needs of patients are being met, and they are reaching full potential as productive adults. The margin of function which allows individuals to live independently is often very small. Early or more pronounced reduction in function associated with aging may make the difference in whether a care giver is required for activities of daily living or there is independent living.

Research into the Health Related Quality of Life, prevalence of disease, potential to avoid disease, availability of care including preventative care is required.

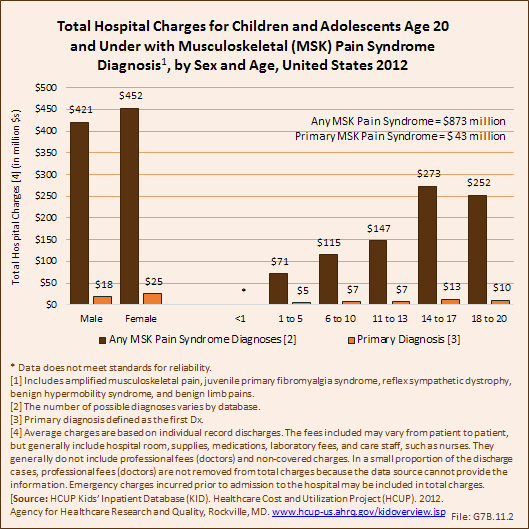

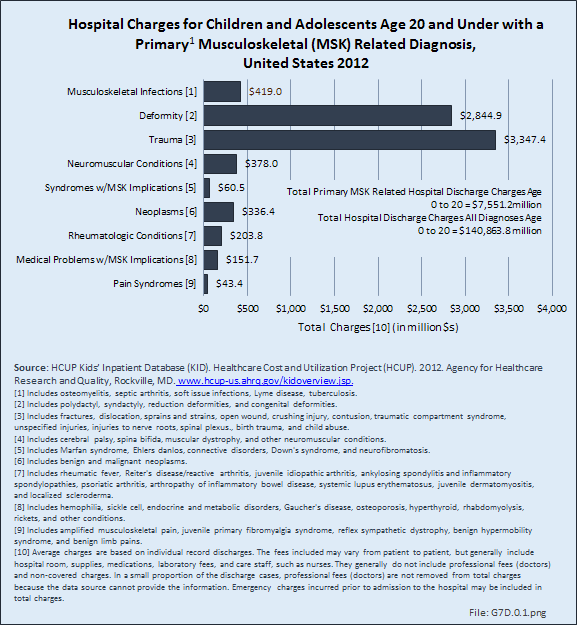

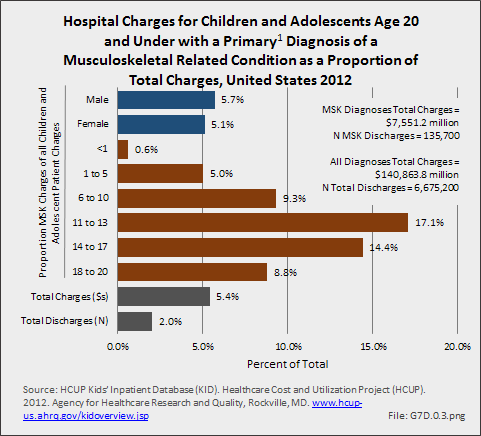

In 2012, total hospital charges for children and adolescents age 20 years and younger with a primary musculoskeletal-related diagnosis were $7.6 billion. Musculoskeletal trauma (injuries) (43%) and deformity (38%) were the major contributors to total hospital charges, but all conditions contribute to the overall economic impact of musculoskeletal conditions in this age group. Furthermore, while musculoskeletal condition hospital charges represent 5.4% of total charges for all medical conditions for the age 20 years and younger age group, the number of discharges represent only 2% of total hospital discharges for any medical condition in this age group, indicating that musculoskeletal conditions may be more expensive to treat than many other childhood conditions. (Reference Table 7.12 PDF [43] CSV [44])

It is important to note that the overall cost of musculoskeletal conditions in the 20 years and younger population is much greater than just hospital charges. First, the $7.6 billion includes only hospitalizations with a primary, or first, diagnosis in the databases, representing less than 1% of 2012 health care visits with any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis. Not included in this burden are expenditures for visits to emergency departments, outpatient clinics, and physicians’ office, as well as other medical care expenditures such as physical therapy, rehabilitation, and medications.

While gender is not a factor in the distribution of hospital charges, age is a major contributor. Children in the middle years of childhood, especially ages 11 to 13 years, have a higher share of total hospital charges (17%) due to musculoskeletal conditions than any other age group. Musculoskeletal condition hospital charges are also a higher share for those age 14 to 17 years (14%) and ages 6 to 10 years (9%).

To fully understand the burden of musculoskeletal diseases on children and adolescents, it is mandatory that data be available on prevalence, health care needs, cost associated with treatment, limitations due to musculoskeletal conditions, and overall impact these conditions have on the lives of children and adolescents. The HCUP KID database [9] provides a tremendous asset in understanding hospitalizations for this analysis, but it, too, has limitations. Primary among these is the inability to determine primary cause for visits, as multiple diagnosis codes may be included with each record, with no way of knowing which is the primary diagnosis. In addition, many health care visits are to a physician’s office, and the database for these visits National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is small and often contains insufficient cases (<35) for reliable analysis even when merging several years of data. This is particularly true for the very young patients (0 to 5 years) and for rare conditions. Injuries occur in sufficient numbers that this is not a problem. However, many conditions had low numbers.

A second key challenge is ensuring that children with chronic medical and musculoskeletal problems have access to care, particularly for those with Medicaid or other government-funded insurance. Low physician reimbursement by government insurance results in fewer physicians who are willing or able to care for these patients, making access to needed specialty care difficult. Additionally, pediatric subspecialists who take care of musculoskeletal conditions are typically located at large children’s hospital in large cities, further reducing access to care for those in rural areas. Because of the unique nature of pediatric musculoskeletal problems and treatments, many adult subspecialists who may be more accessible are unable or unwilling to treat pediatric patients.

A third challenge is the need to track pediatric patients into adulthood to determine lifelong burden of their pediatric musculoskeletal disease. Once a child turns 18 years, the system loses them because they become more mobile and move on to other caregivers. Further, they lose parental insurance or their Medicaid coverage. A better way to obtain long-term follow-up on their history and long-term outcomes of treatment of pediatric musculoskeletal disease is needed.

Poor bone health is being recognized as a key problem in pediatric musculoskeletal disease, one that will last a lifetime. Key factors leading to poor bone health are Vitamin D deficiency and childhood obesity. The current health care data system makes it very difficult to quantify the burden of these problems because they are rarely evaluated as the primary diagnosis. Additionally, patients are rarely admitted or discharged for treatment specific for these diagnoses. In the future, methods for estimating the incidence of these diagnoses more accurately and assessing their contribution to musculoskeletal disease is necessary. Education of the individual, family, and society about the burden of obesity and Vitamin D deficiency is necessary to improve overall bone health in the United States.

Quality of life assessments in children and adolescents that allows better measure of the personal impact of pediatric musculoskeletal disease is lacking.

In assessment of musculoskeletal disease for adults, lost wages and lost workdays are used to quantify burden. There is no corresponding way to measure burden in children. Currently, it is quantified indirectly by measuring lost wages and lost workdays for the child’s caregiver. Better methods for quantifying indirect burden of pediatric musculoskeletal disease is needed.

Better long-term follow-up data on pediatric musculoskeletal conditions is needed. Once patients reach adulthood, it becomes difficult for the physician who cared for their musculoskeletal conditions to keep track of them. This results in difficulty understanding adult manifestations of pediatric musculoskeletal conditions.

Recent international disasters such as the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti each affected hundreds of thousands of people. International disaster relief efforts need better planning for providing relief specific to children.

MUSCULOSKELETAL INFECTIONS

Osteomyelitis: 730.0, 730.1, 730.2, 730.8, 73090, 73091, 73092, 73093, 73094, 73095, 73096,73097

Septic arthritis: 711.0, 711.4

Soft tissue infections (infective myositis): 72800, 72886

Lyme disease: 08881

Tuberculosis: 015

DEFORMITY

Upper Extremity:

Polydactyly: 75500, 75501

Syndactyly: 75510, 75511, 75512

Reduction deformities: 755.2

Other congenital anomalies upper limb: 755.5, 736.0, 736.1, 736.2, 73690, 75489, 75681, 75689

Lower Extremity:

Polydactyly: 75502

Syndactyly: 75513, 75514

Reduction deformities: 755.3

Other congenital anomalies lower limb: 755.6

Congenital deformities: 754.4, 754.59, 754.6, 754.7, 72781, 73400, 736.7, 736.8

Hip and Pelvis:

Congenital deformity of hip joint: 75561, 75562, 75563

Hip joint acquired: 736.3, 73220, 73860

Developmental dysplasia: 754.3

Spine and Pelvis:

Of spinal cord: 742.5

Of vertebral column: 737, 73850, 73200, 75420, 756.1

Other and Unspecified:

Congenital deformities: 754.8, 75540, 75580, 75590, 75682, 75690, 75689

TRAUMA: Fractures, dislocation, sprains and strains, open wound, crushing injury, contusion, traumatic compartment syndrome, unspecified injuries, injuries to nerve roots and spinal plexus

Upper Extremity: 810, 811, 812, 813, 814, 815, 816, 817, 818, 819, 831, 832, 833, 834, 840, 841, 842, 880, 881, 882, 883, 884, 885, 886, 887, 90520, 923, 927, 95891, 95920, 95930, 95940, 95950

Lower Extremity: 820, 821, 822, 823, 824, 825, 826, 827, 828, 829, 836, 837, 838, 844, 845, 90530, 90540, 924, 928, 95960, 95970, 95892

Hip and Pelvis: 835, 843, 84850, 808, 959.1, 953

Spine and Trunk: 805, 806, 807, 846, 847, 809, 875, 876, 90510, 92200, 92210, 92230, 92231, 92232, 92233, 92280, 92290, 926.1, 92680, 92690, 952

Birth Trauma: 767

Child Abuse: 995.5

NEUROMUSCULAR CONDITIONS

Cerebral palsy (CP): 343

Spina bifida (SB): 741

Muscular dystrophy (MD): 359

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT): 35610, 35620

Other: 334, 335, 33600, 336

SYNDROMES WITH MUSCULOSKELETAL IMPLICATIONS

Marfan sydrome/Ehlers Danlos syndrome/other connective tissue disorders: 75982, 75683

Down's syndrome: 75800

Neurofibromatosis (NF): 23770, 23771, 23772

SPORTS INJURIES (Sports injuries data is from NEISS and does not use ICD-9 codes.)

SKELETAL DYSPLASIAS

Dysplasias: 75989, 65580, 73399, 39330

Chondrodystrophy/achondroplasia/hypochondroplasia: 75640

Dwarfism (thanatophoric dysplasia): 25940, 75651

Congenital absence rib: 75630

Osteogenesis imperfecta: 75651

Osteopetrosis: 75652

Other: 75654, 75655, 75656, 75659

NEOPLASMS

Benign:

Benign lesion of bone/cartilage: 213

Lipoma: 21400, 21410, 21420, 21430, 21480, 21490

Benign lesion of CT/ST: 215

Malignant:

Malignancy of bone/cartilage: 170

Malignancy of CT/ST: 171

RHEUMATOLOGIC CONDITIONS

Rheumatic fever: 39000, 39092

Reactive arthritis/Reiter disease (underlying disease, no principal diagnosis): 711.1

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 714.3

Ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory spondylopathies: 720

Psoriatic arthritis: 696

Arthropathy of inflammatory bowel disease: 71310

Systemic lupus erythematosus: 71000

Juvenile dermatomyositis: 71030

Localized scleroderma: 70100, 71010

MEDICAL PROBLEMS WITH MSK IMPLICATIONS

Hemophilia: 00286

Sickle cell: 28260

Endocrine and metabolic disorders: 75650

Gaucher disease (lipidoses/lysosomal storage disorders): 27270

Osteoporosis: 733.0

Hyperthyroid (thyrotosicosis w/wo goiter): 242

Rhabdomyolysis: 72888

Other conditions: 28610, 25890

Rickets (Vitamin D deficiency, phosphorus, and calcium metabolism disorders): 268, 275.3, 275.4

PAIN SYNDROMES

Amplified musculoskeletal pain/Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome: 30789, 72910

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (complex regional3722 pain syndrome/CRPS): 337.2

Benign hypermobility/hypermobility syndrome: 72850

Benign limb pains (“growing pains”): 719.4

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.1.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.1.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.2.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.0.2.csv

[7] http://report.nih.gov/fundingfacts/fundingfacts.aspx

[8] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/2014-report/viig0/children-adolescent-icd-9-cm-codes

[9] http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp

[10] https://www.cpsc.gov/cgibin/NEISSQuery/home.aspx

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.1.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.1.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.2.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.2.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.2.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.2.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.3.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.3.csv

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.4.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.4.csv

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.5.pdf

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.5.csv

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.6.pdf

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.6.csv

[25] http://www.ncys.org/publications/2008-sports-participation-study.php

[26] http://www.physicalactivitycouncil.com/pdfs/current.pdf

[27] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/2013-report/research-funding-care-and-prevention/vii3a-0

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.7.1.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.7.1.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.7.2.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.7.2.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/2014-report/ixac10/childhood-cancers

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.8.pdf

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.8.csv

[35] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/childhood.htm

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.9.pdf

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.9.csv

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.10.pdf

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.10.csv

[40] http://www.stopchildhoodpain.org

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.11.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.11.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.12.pdf

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.12.csv