Musculoskeletal conditions are among the most disabling and costly conditions suffered by Americans. In March 2002, President George W. Bush proclaimed the years 2002–2011 as the United States Bone and Joint Decade, providing national recognition to the fact that musculoskeletal disorders and diseases are the leading cause of physical disability in this country.1,2 At the end of the decade, the multiple associations of health providers treating musculoskeletal diseases realized the work had only begun, and the United States Bone and Joint Initiative (USBJI), a part of the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health, was created.

In December 2012, a study on the Global Burden of Disease and the worldwide impact of all diseases and risk factors found musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis and back pain affect more than 1.7 billion people worldwide, are the second greatest cause of disability, and have the 4th greatest impact on the overall health of the world population when considering both death and disability. Professor Christopher Murray, lead investigator, and the authors of the study underline the need to address the rising numbers of individuals with a range of conditions such as musculoskeletal disorders that largely address disability, not mortality, in the future.3

The goal of USBJI is to improve the quality of life for people with musculoskeletal conditions and to advance understanding and treatment of these conditions through research, prevention, and education. The cornerstone of USBJI is the burden of musculoskeletal disease, defined as the incidence and prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions; the resources used to prevent, care, and cure them; and the impact on individuals, families, and society. Direct costs of the burden of musculoskeletal disease include hospital inpatient, hospital emergency and outpatient services, physician outpatient services, other practitioner services, home health care, prescription drugs, nursing home cost, prepayment, and administration and non–health-sector costs. Indirect cost relates to morbidity and mortality, including the value of productivity losses due to disability or premature death due to a disease and the value of lifetime earnings as well as the impact on quality of life.

The Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States, 3rd Edition, (BMUS) which is available in the following pages on this website, provides numbers to support members engaged in research, education programs, and healthcare policy that will bring about significant advances in the knowledge, diagnosis, and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, and increase the number of resources at the disposal of the healthcare profession and the public at large.

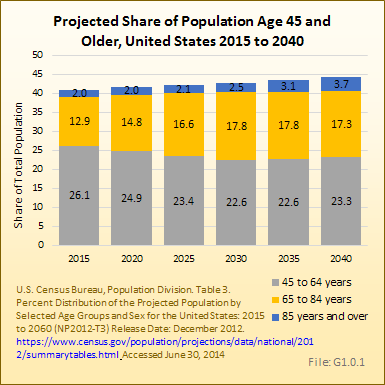

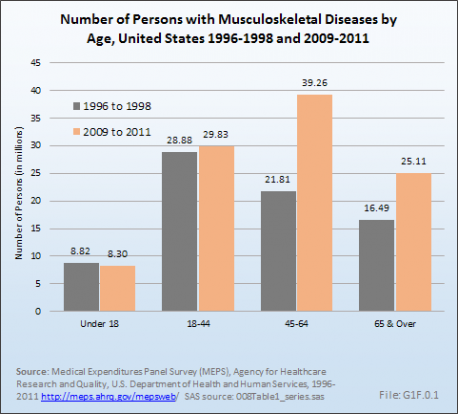

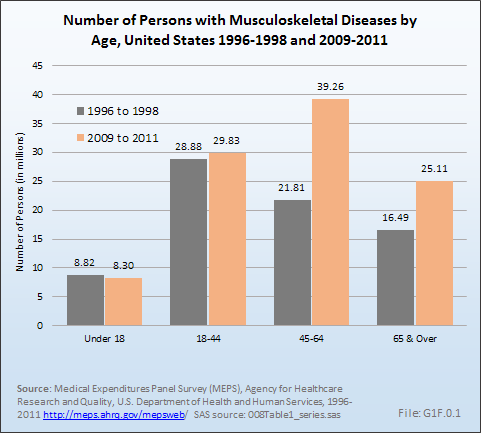

As the US population continues to age in the next 25 years, musculoskeletal impairments will increase because they are most prevalent in the older segments of the population. By the year 2040, the number of individuals in the United States older than the age of 65 years is projected to grow from the current 15% of the population to 21%. Persons age 85 years and older will double from the current <2% to 4%. Health care services worldwide will be facing severe financial pressures in the next 10 to 20 years due to the escalation in the number of people affected by musculoskeletal diseases. Bone and joint disorders account for more than one-half of all chronic conditions in people older than 50 years of age in developed countries, and are the most common cause of severe, long-term pain and disability.4

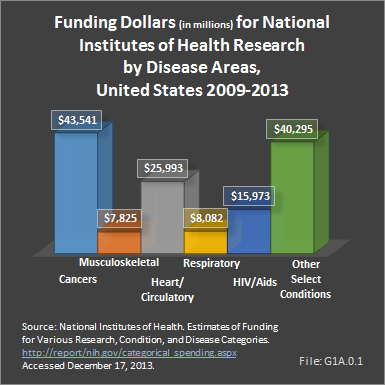

In spite of the widespread prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions and three of the most costly healthcare conditions—trauma, back pain, and arthritis—being musculoskeletal, musculoskeletal conditions are not among the top ten health conditions receiving research funding,1 primarily due to the low mortality from musculoskeletal conditions in comparison with other health conditions. However, the morbidity cost of musculoskeletal conditions is tremendous because musculoskeletal conditions often restrict activities of daily living, cause lost work days, and are a source of lifelong pain.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine wrote “In setting national priorities NIH should strengthen its analysis in the use of health data, such as burdens of disease, and of data on the impact of research and the health of the public.”2 National health data in several countries show that musculoskeletal conditions rank among the top health concerns for citizens in the United States and worldwide. By current US estimates, more than 50% of the disabling conditions reported by of persons age 18 years and older are related to musculoskeletal disorders, yet research funding to alleviate these major health conditions remains substantially below that of other major health conditions such as cancer and respiratory and circulatory (eg, heart) diseases. (Reference Table 1.5.1 PDF [2] CSV [3])

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) was formed in 1987. In subsequent years, research funding for these conditions has declined in relative terms, and since 2000, less than 2% of the annual National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget has been appropriated to musculoskeletal disease research. In fact, the annual average rate of funding continues to decline. Over the last five years (2009 to 2013), funding for musculoskeletal conditions from NIH totaled $7.8 billion, while that of cancers and heart/circulatory disorders totaled $43.5 billion and $25.9 billion, respectively. (Reference Table 1.1.1 PDF [4] CSV [5], and Table 1.1.2 PDF [6] CSV [7])

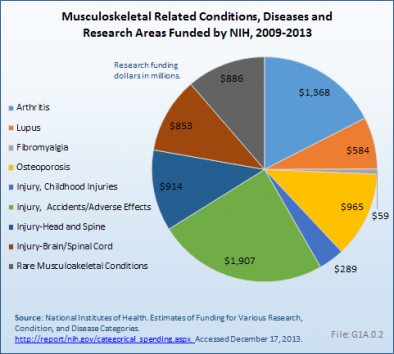

In spite of the major health care burden presented by musculoskeletal conditions, research funding falls well below that of most other conditions. Injury research commands half of the musculoskeletal condition research dollars ($4 billion) from NIH for the years 2009 to 2013. Funding for arthritis research is second, at $1.4 billion, followed by osteoporosis ($965 million). These numbers are well below the $8.6 to $55.2 billion in funding for the top 25 NIH research areas. (Reference Table 1.1.3 PDF [8] CSV [9])

Since 1998, NIAMS has received 2.2% of research project grants, with funding at less than 2% of total grant dollars. Career development awards during this period have risen from 2.9% in 1998 to 4.5% in 2013. (Reference table 1.1.4 PDF [10] CSV [11])

"Time and again, when the global burdens of disease are enumerated, musculoskeletal conditions rank high. Now we see that that rank is increasing. Although research funding reflects a long-term bias towards diseases with high mortality rates, the Global Burden of Disease project indicates that much of the growth in disease burdens has occurred for conditions that cause high disability rates. Redressing the funding disparity should become a high priority," (Edward H. Yelin, PhD, MCP, co-chair, BMUS3)

Although musculoskeletal conditions are common, disabling, and costly, they remain under-recognized, under-appreciated, and under-resourced. This book provides a strong case for the immediate and ongoing need to understand and support musculoskeletal conditions and reduce the burden it brings to our people.

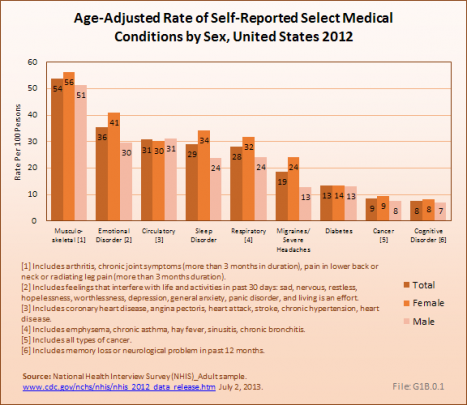

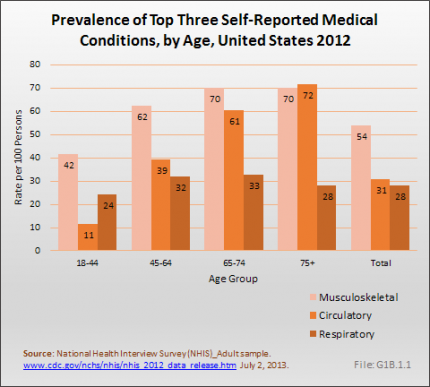

In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2012, musculoskeletal medical conditions were reported by 126.6 million adults in the United States, representing more than one in two persons age 18 and over of the estimated 2012 population. The rate of chronic musculoskeletal conditions found in the adult population is 76% greater than that of chronic circulatory conditions, which include coronary and heart conditions, and nearly twice that of all chronic respiratory conditions. On an age-adjusted basis, musculoskeletal conditions are reported by 54 persons per every 100 in the population. This compares to a rate of 31 and 28 persons per every 100 in the population for circulatory and respiratory conditions, respectively. The NHIS annual survey of self-reported health conditions is used throughout this chapter to highlight chronic health conditions of the US population. (Reference Table 1.2.1 PDF [12] CSV [13])

On an age-adjusted basis, females report a higher rate of occurrence than males for most major medical conditions. Among females, 56 out of every 100 females in the population report musculoskeletal conditions; among males the rate is only slightly lower at 51 per 100, a slight increase in recent years. (Reference Table 1.2.1 PDF [12] CSV [13])

Musculoskeletal conditions are found among all age groups, with the proportion of persons reporting these conditions increasing with age. Musculoskeletal conditions are reported by nearly three of four (70%) persons age 65 years and over. This compares to the 61% of persons age 65 to 74 years, and only slightly less than the 72% of those aged 75 years and older, reporting circulatory conditions, the majority of whom report chronic hypertension. (Reference Table 1.2.2 PDF [14] CSV [15] and Table 1.3.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Musculoskeletal conditions were reported at a higher rate among whites and persons of mixed or other races, with 56 and 57 persons, respectively, in every 100 person in the population reporting a musculoskeletal condition. Among persons of the black/African American race, 48 in 100 reported a musculoskeletal condition. Persons of Asian descent reported the lowest level of musculoskeletal conditions, at a rate of 40 persons in every 100 persons in the population. (Reference Table 1.2.3 PDF [18] CSV [19]) The rate of musculoskeletal conditions among black/African Americans and those of Asian descent increased by several percentage points from those reported in 2008.1

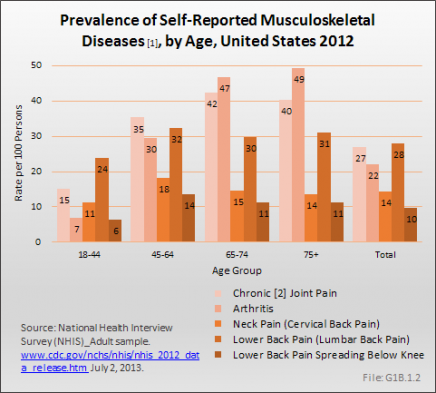

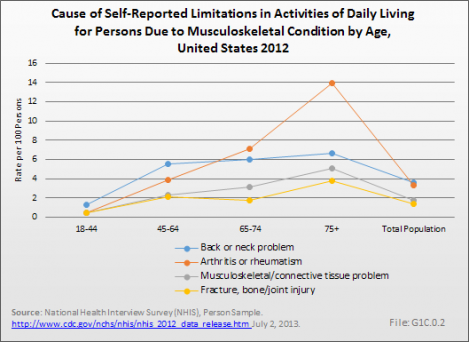

Chronic joint pain increases with age, but peaks in the 65- to 74-year age group. Among the 63.1 million persons reporting chronic joint pain in 2012, knee pain is the most frequently cited, with 40 million people reporting knee pain. Chronic knee pain is reported by all ages older than 18![Proportion of Population [1] Age 18 and Older Reporting Joint Pain [2], United States 2012 Proportion of Population [1] Age 18 and Older Reporting Joint Pain [2], United States 2012](https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/resize/G1B.2-239x416.png) years, with more than one in four aged 65 and older reporting knee pain. Shoulder pain, reported by 18.7 million of those age 18 and older, is the second most common joint for chronic pain, with rates fairly equal for those age 45 and older. Hip pain was reported by 15.3 million persons age 18 and older.

years, with more than one in four aged 65 and older reporting knee pain. Shoulder pain, reported by 18.7 million of those age 18 and older, is the second most common joint for chronic pain, with rates fairly equal for those age 45 and older. Hip pain was reported by 15.3 million persons age 18 and older.

While multiple joints can be the source of chronic joint pain, overall, one in four people over the age of 18 report chronic joint pain. The ratio jumps to more than two in five after the age of 65 years. However, even among younger adults age 18 to 44, about one in six report chronic joint pain. (Reference Table 1.4.2 PDF [24] CSV [25])

Females report higher rates of chronic joint pain than do males, with the exception of shoulder pain. Race is not a variable in the rate of chronic joint pain, with the exception of those of Asian race, who report lower joint pain rates than other racial groups. (Reference Table 1.4.1 PDF [26] CSV [27] and Table 1.4.3 PDF [28] CSV [29])

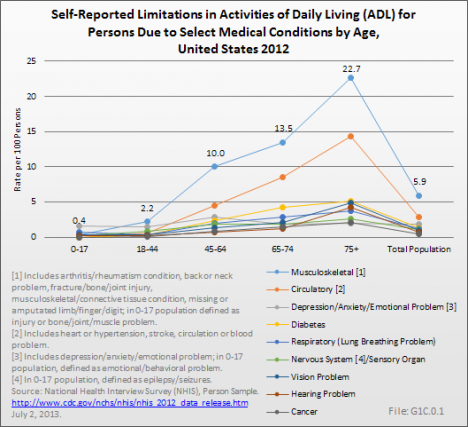

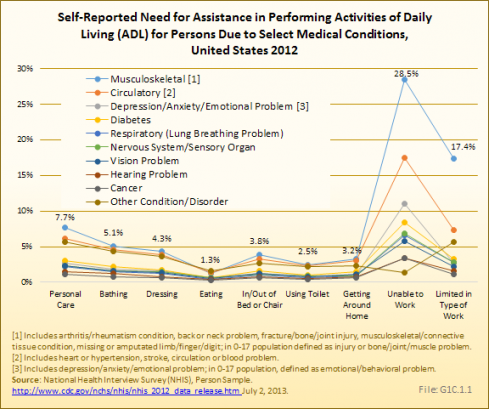

While most major medical conditions have a higher proportion of persons age 18 years and older who are unable to perform ADL or to work, the much higher incidence of musculoskeletal conditions results in the highest limitation rates. For example, 60% of persons with a circulatory condition report they are unable to work because of the condition, while 48% of persons with a musculoskeletal condition report this. However, the rate per 1,000 persons in the general population unable to work is 28.5 for a musculoskeletal condition, compared to 17.4 for persons with a circulatory condition. (Reference Table 1.7 PDF [40] CSV [41])

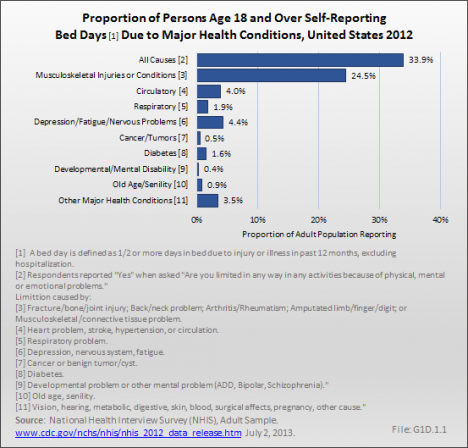

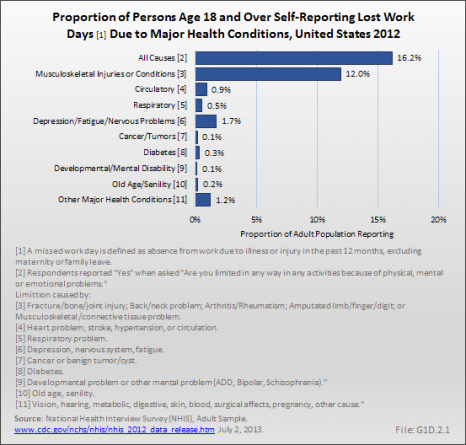

Respondents to the 2012 NHIS self-reported the number of bed days and lost work days they experienced in the previous 12 months due to a variety of medical conditions. A bed day is defined as one-half or more days in bed because of injury or illness in past 12 months, excluding hospitalization. A missed, or lost, work day is defined as absence from work because of illness or injury in the past 12 months, excluding maternity or family leave.

Although the exact cause of these bed and lost work days cannot be determined because some respondents reported multiple health conditions, 70% of persons reporting bed and lost work days reported having a musculoskeletal condition. This is more than twice the proportion reporting depression, the second most common medical condition listed for causing lost work days, and five or more times the proportion for other major health conditions. Overall, the high proportion of workers reporting lost work days or bed days as a result of a musculoskeletal condition results in an economic burden on the economy—much higher than that reported for chronic circulatory or chronic respiratory conditions. (Reference Table 1.8.3 PDF [42] CSV [43])

More than one in three persons (34%) reported at least one bed day in the previous 12 months because of a medical condition. One in four (24.5%) reported having a musculoskeletal condition, six times the rate reported for depression and circulatory conditions, the second and third most common conditions reported.

The average number of bed days reported by persons with musculoskeletal conditions was 9, for a total of more than 752 million bed days among persons with these conditions. Although the average number of bed days reported for other major health conditions was greater than for musculoskeletal conditions, the much higher proportion of the population with bed days because of musculoskeletal conditions resulted in the much higher number of total days. (Reference Table 1.8.1 PDF [44] CSV [45] and Table 1.8.3 PDF [42] CSV [43])

Females and persons age 45 to 64 report higher rates of bed days because of musculoskeletal conditions than do males and adults age 18 to 44 or over 65. (Reference Table 1.8.4 PDF [46] CSV [47] and Table 1.8.5 PDF [48] CSV [49])

Twenty-eight million persons with a musculoskeletal condition, or roughly one in eight people in the prime working ages between 18 and 64 in the United States in 2012, reported lost work days in the previous 12 months, totaling more than 216 million days. Lost work days for persons with a musculoskeletal conditions accounted for more than four times as many days as the second highest condition, which was depression. Chronic circulatory conditions, including high blood pressure and heart conditions, accounted for 32.3 million lost work days, and were reported by only 1% of the working age population. Chronic respiratory conditions accounted for 16.5 million lost work days. On average, workers lost nearly 8 days in a 12-month period because of musculoskeletal conditions. Workers lost an average of 15 days because of circulatory conditions, but with a much smaller prevalence than musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 1.8.2 PDF [50] CSV [51], and Table 1.8.3 PDF [42] CSV [43])

As with bed days, females and persons age 45 to 64 report higher rates of lost work days because of musculoskeletal conditions than do males and adults age 18 to 44 or over 65. (Reference Table 1.8.4 PDF [46] CSV [47], and Table 1.8.5 PDF [48] CSV [49])

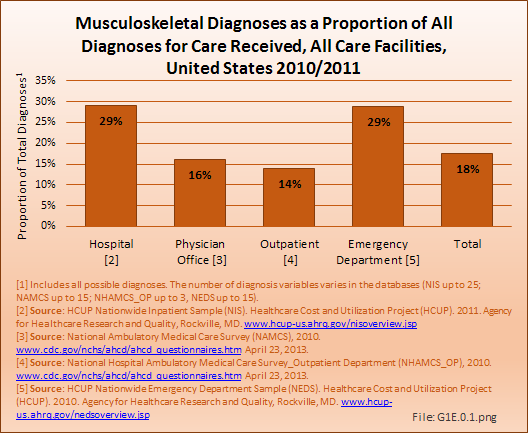

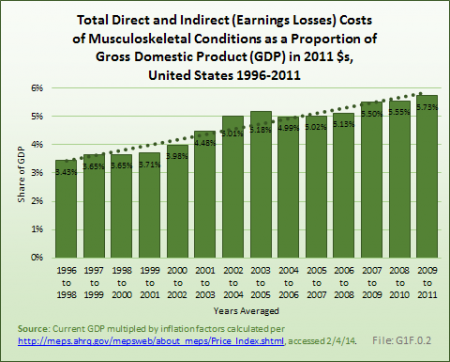

The increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions, along with a growing and aging population, has resulted in more than a 50% increase in total aggregate direct cost to treat persons with a musculoskeletal condition over the past decade, in constant 2011 dollars. For the years between 2009 and 2011, the annual average direct cost in 2011 dollars for musculoskeletal health care—both as a direct result of a musculoskeletal disease and for patients with a musculoskeletal disease in addition to other health issues—is estimated to be $796.3 billion, the equivalent of 5.2% of the national gross domestic product (GDP).

Total medical care costs are the costs for all of an individual’s conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions. Incremental medical care costs are that part of total medical care costs attributable solely to the musculoskeletal conditions. Incremental medical costs for musculoskeletal conditions for the years between 2009 and 2011 are estimated to be $212.7 billion, in 2011 dollars. (Reference Table 10.6 PDF [66] CSV [67], and Table 10.14 PDF [64] CSV [65])

Indirect costs measure disease impact in terms of lost wages due to disability or death. Indirect costs, like medical care costs, can be estimated and calculated in total for all the medical conditions an individual has, and as the increment attributable solely to musculoskeletal conditions.

Indirect cost for persons age 18 to 64 with a work history add another $77.5 billion, or 0.5% of the GDP in between 2009 and 2011, to the cost for all persons with a musculoskeletal disease, either treated as a primary condition or in addition to another condition. Annual indirect costs attributable to musculoskeletal disease alone (incremental cost) account for an estimated $130.7 billion. Indirect costs attributable to musculoskeletal disease are greater than total indirect costs because of a 4% gap in the probability of working between persons with and without a musculoskeletal condition and a lower mean income. (Reference Table 10.12 PDF [68] CSV [69])

The aging of the US population puts an increased proportion of the population at the ages of highest risk of the onset of musculoskeletal conditions and, among those with these conditions, at the ages of highest severity levels. The problem of aging is made more severe by the fact that many major chronic diseases are more prevalent in late middle age and among the elderly. In fact, most of the latter group has two or more chronic diseases. The impact of comorbidity is reflected in the cost data presented in this volume. Not only are the incremental costs, that is, those attributable to the musculoskeletal conditions, high among those age 45 and older, but the total medical costs they experience are also higher in these age ranges. The problems of an aging population are exacerbated by the co-occurrence of multiple chronic diseases. (Reference Table 10.9 PDF [70] CSV [71]).

The increased prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions associated with the aging population will necessarily place increased demands on the health care system. However, the growth in the health manpower pool is not keeping pace with the growing prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions. In fact, two medical specialties focused on the care of persons with these diseases, rheumatology and geriatrics, are having a difficult time recruiting new physicians because they are not among the most highly remunerated specialties.

It is also the case, as documented in Section I.A.O: Funding [72] above, that research funding for musculoskeletal conditions, relatively small to begin with, is not keeping up with the growing importance of this disease group. Prior research has led to dramatically improved treatments for inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (principally because of the development of biological treatments) and to mechanical ones such as osteoarthritis (principally because of the improvement in total joint replacement rates). However, in order to deal with the increased numbers of patients associated with the aging population, research funding must be expanded in sheer dollars and in scope to encompass the cause, treatment, and organization of care.

Links:

[1] http://www.thelancet.com/themed/global-burden-of-disease

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.1.pdf

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.1.csv

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.1.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.1.csv

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.2.pdf

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.2.csv

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.3.pdf

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.3.csv

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.4.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.1.4.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.1.pdf

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.1.csv

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.2.pdf

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.2.csv

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.2.pdf

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.2.csv

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.3.pdf

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.2.3.csv

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.1.pdf

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.1.csv

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.3.pdf

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.3.3.csv

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.2.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.2.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.1.pdf

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.1.csv

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.3.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.4.3.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.2.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.2.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.2.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.2.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.1.pdf

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.1.csv

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.3.pdf

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.5.3.csv

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.3.pdf

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.6.3.csv

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.7.pdf

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.7.csv

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.3.pdf

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.3.csv

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.1.pdf

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.1.csv

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.4.pdf

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.4.csv

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.5.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.5.csv

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.2.pdf

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.8.2.csv

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.1.pdf

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.1.csv

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.2.pdf

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.2.csv

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.3.pdf

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T1.10.3.csv

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10001.1.pdf

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10001.1.csv

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10002.1.1.pdf

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10002.1.1.csv

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10011.10.pdf

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10011.10.csv

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10015.14.pdf

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10015.14.csv

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10007.6.pdf

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10007.6.csv

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10013.12.pdf

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10013.12.csv

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10010.9.pdf

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T10010.9.csv

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/2013-report/i1/introduction