Musculoskeletal pain syndromes, including amplified musculoskeletal pain, juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, benign hypermobility, and benign limb pains, are common diagnoses in the pediatric population. A systematic review examining the prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain found a range of prevalence rates between 4% and 40% in children. Rates were generally higher in girls and increased with age.1 It is estimated that 5% to 8% of new patients presenting to North American pediatric rheumatologists have a musculoskeletal pain syndrome.2

Amplified musculoskeletal pain and juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome are related conditions with the common feature of diffuse pain involving at least three major body parts for at least 3 months. Patients also typically have sleep disturbance and other somatic complaints, such as headaches and abdominal pain. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), now also called complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), is a form of amplified pain in which autonomic dysfunction develops in an extremity, often following injury or trauma. The affected limb becomes swollen and discolored and the area can be very painful with light touch (allodynia). The recommended treatment for these conditions includes restoring normal sleep patterns, a therapy program with a focus on exercise and desensitization, and cognitive behavioral therapy. Some patients require treatment in an in-patient setting.3

Benign limb pains, also sometimes referred to as “growing pains,” are most common in children age 2 to 5 years. Children with benign limb pains tend to complain of pain at night, often awaking from sleep due to pain. These symptoms tend to resolve with age. Benign hypermobility is diagnosed in patients who have hypermobile joints4, without an underlying connective disuse disorder. This condition is common, affecting 8% to 20% of White populations. Anterior knee pain and back pain are more common in hypermobile vs nonhypermobile individuals.2

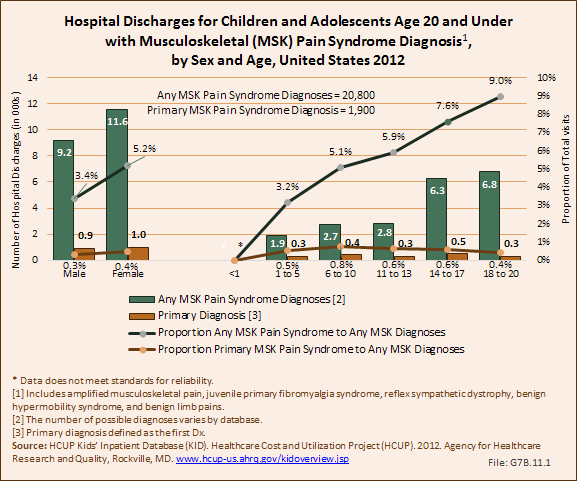

Pain syndromes were diagnosed in more than 2.5 million children and adolescent health care visits in 2012, of which 66% (1.7 million) had a primary diagnosis of a pain syndrome. Less the 1% of children and adolescents with any pain syndrome diagnoses were hospitalized (20,800), while a tiny fraction (1,900) with a primary diagnosis had a hospital discharge. The majority of children and adolescents with a pain syndrome diagnosis were seen in physicians’ offices. (Reference Table 7.1.1 PDF [2] CSV [3] and Table 7.1.2 PDF [4] CSV [5])

Females were hospitalized with a pain syndrome diagnosis in slightly higher numbers than males, both for any diagnoses and as a primary diagnosis. Pain syndrome diagnoses increase as a contributing diagnosis in older children, but as a primary diagnosis age is not a factor.

Any diagnoses of pain syndrome accounted for just over 4% of hospitalizations for any musculoskeletal condition diagnosis, and 0.3% of all hospitalizations for any health care condition. Hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis pain syndrome were 0.4% of all musculoskeletal diagnoses and a tiny portion of hospitalizations for any health condition diagnosis. (Reference Table 7.11 PDF [6] CSV [7])

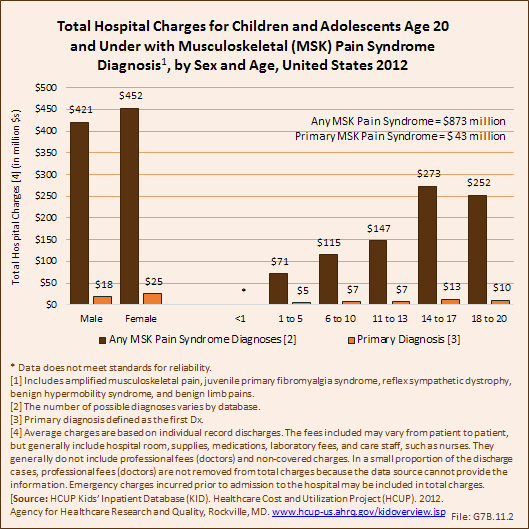

Total charges averaged $42,000 for a mean 5.6-day stay when children and adolescents were hospitalized with any diagnosis of a pain syndrome along with other medical conditions. With a primary pain syndrome diagnosis, the stay was shorter (3.1 days), and mean charges about half that of pain syndrome as a contributing condition ($22,900). Age and sex were not significant factors in length of hospital stay and average charges for a medical problem diagnosis. Total hospital charges for primary pain syndrome diagnosis discharges in 2012 were $43.4 million. (Reference Table 7.11 PDF [6] CSV [7])

Links:

[1] http://www.stopchildhoodpain.org

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.1.pdf

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.1.csv

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.2.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.1.2.csv

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.11.pdf

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T7.11.csv