Arthritis is a condition impacted by both sex and gender. Women are more likely to present with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis than are men as reflected by both self-report and radiographic studies. Specific joints appear to be at particular risk of sex-based disparities in incidence. Sodha noted in a study of hand radiographs that, after the age of 40 years, women were significantly more likely than men to have incidentally noted radiographic osteoarthritis of the hand, especially the first carpometacarpal joint.1 This incidence increased with age, especially for women, with more than 90% of women over the age of 80 years having this finding.

The increased risk of inflammatory arthritis likely reflects the overall higher rate of inflammatory conditions found in all organ systems among women. This may reflect an impact of sex hormones, especially alterations in estrogen levels, as estrogen has been found to impact B and T cell homeostasis, as well as to impact interferon regulation.2 A variety of etiologies have also been proposed, but contradictions remain in the available evidence.

The etiology of the higher rate of osteoarthritis among women also is still under debate and appears to be multifactorial. There is some indication that osteoarthritis in women has a different course than seen in men. Maillefert 3 followed 508 patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and noted that women are more likely to have polyarticular disease (pain in multiple joints), superolateral migration of femoral head, more severe symptoms, and more rapid loss of joint space. Some conditions that may increase the risk of osteoarthritis are more common, or differ in presentation in women. For example, the rates of acetabular dysplasia and pincer-type femoroacetabular impingment are higher in women. Potential explanations for differences in osteoarthritis of the knee, one of the more commonly involved joints, includes a higher lower-extremity–injury rate, differing lower-extremity alignment, lower muscle strength, and the impact of estrogen loss after menopause.

As will be discussed in another section, women are significantly more likely to sustain non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Roos4 noted that women who had sustained an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury were not only significantly more likely to have osteoarthritis of the knee than other women of the same age, they were also more likely to have osteoarthritis than men who had sustained an ACL injury at a similar age. This may reflect differing inflammatory responses at the time of injury or other factors that affect the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Women with radiographic findings of osteoarthritis of the knee, including those without self-reported symptoms, have been noted to have weaker quadriceps than those without such changes; this relationship has not been investigated among men.5 This relative muscular weakness may translate into greater rate and degree of loading or force transmission to articular cartilage.

The impact of estrogen loss on articular cartilage and the consequent development of osteoarthritis has not been clearly defined. Estrogen receptors have been identified on chondrocytes and synoviocytes. Estrogen appears to inhibit production of matrix metalloproteinases and, thus, may help to inhibit cartilage degradation. Articular cartilage defects appear to progress more rapidly in ovariectomized (OVX) rats than they do in native rats; these defects progress more slowly in OVX rats treated with estrogen or SERMs. There are limited clinical studies in humans, and the relative impact of estrogen loss on developing osteoarthritis has not been identified. Estrogen also influences ligamentous laxity, and its loss may represent one of the many factors leading to an increased risk of osteoarthritis among women.

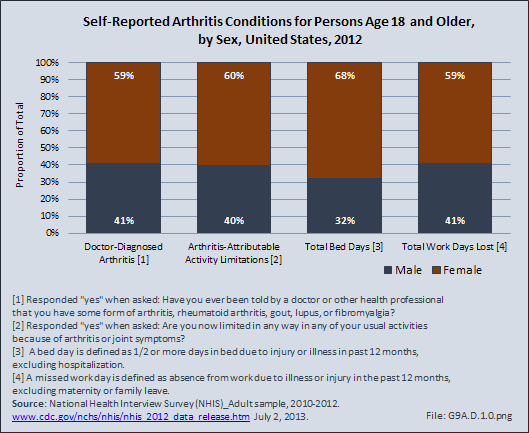

Women are affected by arthritis at a higher rate than are men. Three out of five persons who self-report they have been told by a doctor that they have some form of arthritis are women. Women also are 50% more likely to report they have limitations with activities of daily living because of their arthritis.

Women also report in higher numbers they spent at least one-half day in bed in the previous 12 months due to an arthritis condition, and they reported a higher mean number of days spent in bed (25.7 versus 21.2 days for men). As a result, women accounted for 68% of all bed days attributed to arthritis conditions in 2012.

Although women reported missing work in the previous 12 months due to arthritis in higher numbers than men did, they reported a similar mean number of days lost. Still, women accounted for 59% of total lost workdays in 2012, attributable, at least in part, to an arthritic condition. (Reference Table 9A.4.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

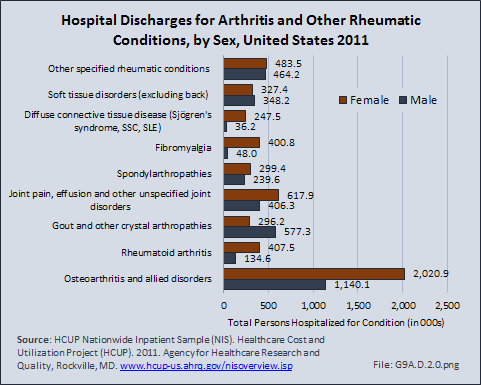

In spite of the frequency and pain severity related to arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions (AORC), AORC account for only a small portion of hospital discharges. Visits to a physician’s office or alternative type of care account for the majority of health care related to AORC. However, among the 6.6 million hospital discharges for an AORC in 2011, 60% were women.

Among the nine major conditions defined by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Arthritis Division [3] as AORC, gout is the only condition where men are affected at a higher rate than women (66% of discharges versus 34%). Soft tissue disorders are found in about equal numbers between men and women.

Women are far more likely to have a diagnosis of fibromyalgia (89%) or diffuse connective tissue diseases (Sjögren's syndrome, SSC, SLE) (87%), than are men. Women also accounted for three-fourth (75%) of discharges with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, and two-thirds (64%) of discharges diagnosed with osteoarthritis. (Reference Table 9A.4.2 PDF [4] CSV [5])

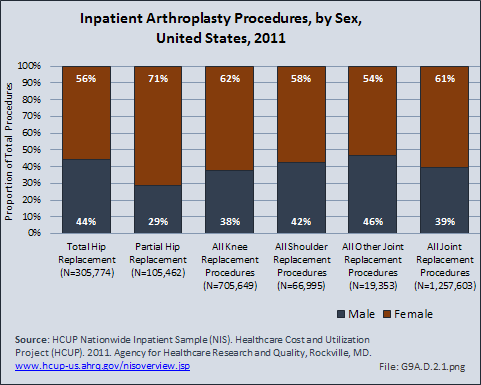

Joint replacement (arthroplasty) procedures are usually performed when osteoarthritis and associated disorders have damaged joints to a point where it is extremely painful to walk and function is impacted. However, there are no objective indications for arthroplasty. Because of the higher rate of osteoarthritis found in women than in men, women are somewhat more likely to receive a joint replacement. (Reference Table 9A.4.2 PDF [4] CSV [5])

Although women receive more joint arthroplasty than do men, some studies have indicated that women are receiving arthroplasty procedures at a lower rate than anticipated, frequently reflecting the impact of gender on health.1 Hawker et al noted that women and men were equally likely to be willing to undergo arthroplasty. They also noted that women were less likely than men to have spoken to a physician regarding joint arthroplasty.1 Other studies noted that women were less likely than men to be referred by their primary care physician for consideration of joint arthroplasty, after controlling for other medical conditions.2,3 These potential delays in joint arthroplasty have significant impact. Katz et al noted that women were significantly more disabled than men by the time they underwent the procedure,4 and Ackerman et al noted that women had a significantly worse quality of life than did men during the time they were waiting for their joint arthroplasty.5 Holtzman et al noted that prior to surgery, more women than men have reported severe pain with walking, needing assistance with walking, needing help with housework, and issues walking across room or less distance; these findings were unrelated to age or comorbidities.6 Although both sexes improve when they have joint arthroplasty, some studies have indicated that women continue to have lower functional scores after surgery than men, potentially reflecting poorer function prior to the procedure and the older age of female patients undergoing arthroplasty. 7,8

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.1.csv

[3] http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.2.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/T9A.4.2.csv