[9]

[9]

The healthcare utilization and economic cost of musculoskeletal diseases section looks at the burden of musculoskeletal conditions both on individuals who have them and the overall US economy.

The economic analyses presented in this chapter are based on a definition of musculoskeletal disease that includes all condition groups discussed in other sections of this website, including low back and neck pain (spine), arthritis and joint pain, osteoporosis, musculoskeletal injuries, and a category of "other" for all remaining conditions. Key estimates were also conducted using more expansive definitions of musculoskeletal diseases and condition groups hereinafter referred to as the broader AAOS definitions. These definitions include all conditions mentioned previously in addition to musculoskeletal conditions that are a consequence of another disease (eg,. bone metastases from cancer). The list of ICD-9-CM codes used in the primary and broader AAOS definitions of musculoskeletal disease can be found in the codes section [1]. In addition, specific conditions and subgroups (ie, connective tissue disease, gout, osteoarthritis and allied disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, other and unspecified conditions of the back, and musculoskeletal disease among children and adolescents) are also examined.

The economic impact measures presented in this chapter include two components: direct medical costs and indirect costs. These costs may be total or incremental, and can be presented as per-person or aggregate costs.

Direct medical costs estimated here capture four types of healthcare resources consumed: ambulatory visits (to both physicians and non-physicians), prescription medications, home health care visits, hospital discharges, and “residual” (all other types of care). Direct medical costs in this chapter measure actual amounts paid, rather than charges. Indirect costs estimated in this chapter are those associated with lost wages. In this edition of BMUS, we have subset analysis of lost wages not just to individuals with a work history, but to those ages 18 to 64 — the typical age range for persons in the workforce. Previous editions of BMUS did not subset lost wage analyses by age, therefore this edition yields lower numbers of individuals in the workforce and, therefore, lower indirect cost estimates when compared with previous editions.

All-cause costs include medical expenditures or lost wages for persons with musculoskeletal disease, regardless of whether those costs are due to the musculoskeletal disease or another medical condition.

Incremental costs are those estimated as attributable to musculoskeletal disease. Essentially, incremental costs are calculated as the difference in costs for those patients with musculoskeletal conditions versus costs simulated for those individuals in the absence of musculoskeletal conditions. The methodology for calculating incremental costs was revised in this edition of BMUS and generally results in estimates that are somewhat lower than those presented in the past. We believe the new methodology more accurately reflects estimated costs.

Aggregate costs for both direct and indirect costs are the sum of per-person costs across all individuals with the condition. We provide aggregate all-cause and incremental costs for all musculoskeletal conditions combined, as well as for condition subgroups separately.

The data source for all estimates in this chapter is the US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Medical Expenditures Panel Survey [2] (MEPS), using "Appropriate Price Indices for Analysis of Health Care Expenditures or Income Across Multiple Years [3]", from the MEPS. The MEPS is a set of large-scale surveys of families and individuals, their medical providers, and employers across the United States. National estimates are calculated by using sampling weights supplied with the survey files. MEPS is the most complete source of data on the cost and use of health care and health insurance coverage currently available.

To demonstrate the effect of musculoskeletal conditions on the US economy, aggregate costs as a share of the Gross Domestic Product [4] [5](GDP) are shown. The GDP is the market value of all goods and services produced in the United States. Because it is released annually, it can be used to measure changes in the size of the economy over time. The GDP is the best known of the national income and product accounts (NIPA), and is often used to create a comparison measure across years.

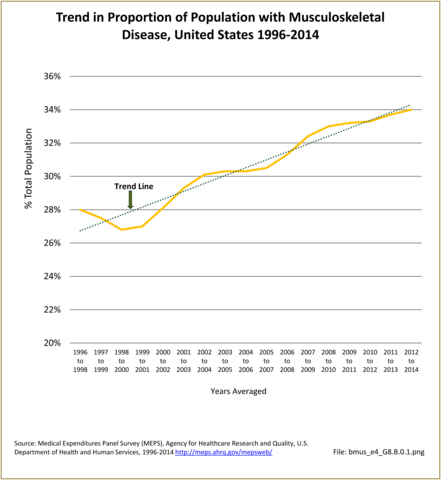

We estimate that 107.5 million persons annually experienced musculoskeletal disease in the 2012-2014 period, an increase of 31.5 million since 1996-1998. Our estimates, based on analysis of MEPS data, may differ from those derived from other sources due to variations in data collection and definitions for musculoskeletal disease. This is over one-third of the population affected by a musculoskeletal condition at least once per year in the 2012-2014 period — an increase of 6 percentage points between from 1996-1998 (28.0% to 34.0%). (Reference Table 8.1.1 PDF [6] CSV [7])

Using the broader AAOS definition of musculoskeletal diseases, an average of 162.4 million (51.4% of the population) reported such conditions annually over the 2012-2014 period, an increase from the 121.1 million (44.7%) reporting the conditions in 1996-1998. (Reference Table A8.1.1 PDF [10] CSV [11])

Although musculoskeletal diseases are more prevalent among people age 65 and older, because there are more individuals in the age range 45-64 at the current time due the size of the baby boom cohort, a larger percentage of those reporting musculoskeletal conditions in 2012-2014 were 45-64 (37.9%) than were 65 or older (25.9%). A major share of those reporting these conditions in 2012-2014 were also in early adulthood, 18-44 years of age (28.6%), while fewer than one in 12 occurred among those less than 18 years of age (7.7%). (Reference Table 8.1.1 PDF [6] CSV [7])

The overall increase in the prevalence rate of musculoskeletal diseases, from 28.0/100 persons in 1996-1998 to 34.0/100 in 2012-2014, masks different rates of change for specific musculoskeletal conditions. The prevalence rate of arthritis and joint pain almost doubled during this time, from 10.7 to 20.8/100 and the prevalence rate of osteoporosis increased by about 50%, from 1.2 to 1.8/100. However, there was relatively little change in the prevalence rate of spine conditions (10.1/100 in 1996-1998 and 11.0/100 in 2012-2014) and of injuries (8.6 and 8.3/100 in the two periods, respectively). Although the prevalence rate of the residual category, “Other Musculoskeletal Conditions” appeared to increase, from 4.4 in 1996-1998 to 6.2/100 in 2012-2014, this may be due to changes in detection and coding conventions.

As noted above, the overall prevalence of spine conditions changed little between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014; however, the number of persons reporting the conditions increased from 27.4 million in the earlier period to 34.9 million in the latter due to population growth. Nearly three-fourths of spine conditions occur in the working-age population, with just under a third reported by those aged 18-44 in 2012-2014 while another 39.1% reported by those 45-64 during this time frame. The high prevalence in these working-age groups explains the high rate of workers’ compensation and disability cases associated with spine conditions. Nevertheless, a significant share of spine conditions was reported by those 65 and older in 2012-2014 (23.1%), the prevalence rate among persons this age group rising from 16.1/100 in 1996-1998, or by more than 40% in relative terms. (Reference Table 8.1.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Among the major subgroups of musculoskeletal diseases, arthritis and joint pain have the highest prevalence. In 1996 to 1998, 29.0 million persons (10.7%) reported one or more conditions related to arthritis and joint pain; by 2012-2014, 65.6 million persons (20.8%) reported one or more such conditions. However, the increased number of people with these conditions between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014 cannot be attributed solely to the increased size of the underlying population as methodological changes in MEPS over time improved the accuracy of capturing these conditions. The aging effect of the baby-boom generation has resulted in an increase in the proportion of arthritis cases among those age 45 to 64 years as they reach the typical onset age for arthritis. As the baby boomers continue to age, the proportion of persons with arthritis in the 65-year and older age group will increase as well. In 1996-1998, 25.6% of persons reporting arthritis were age 18 to 44 years and 37.5% were age 45 to 64 years. By 2012-2014, the proportion of persons aged 18-44 years reporting arthritis had declined slightly to 23.7% while the proportion among those aged 45-64 had increased to 44.0%. (Reference Table 8.1.3 PDF [18] CSV [19])

Population aging has also led to a dramatic increase in the number of individuals with osteoporosis. In the period from 1996-1998, 3.2 million people (1.2% of the population) indicated they had these conditions, but by 2012-2014, 5.7 million (1.8% of the population) reported having them. However, the prevalence rate in MEPS has declined from a high of 2.7% in 2004-2006, 2005-2007, and 2006-2007 to the current rate, 1.8%. The prevalence as reported in MEPS is substantially lower than numbers reported in other sources, even though the category in this chapter is not limited to osteoporosis-related conditions. Estimates of the number of persons with osteoporosis and low bone mass, the precursor to osteoporosis, were 53.6 million in 2010, and projected to increase to 71.4 million by 2030.1

About 38% of persons in the MEPS reporting these conditions are age 45 to 64 years, increasing the likelihood that these individuals will suffer from falls and fractures for the relatively long future they can expect to live with this condition. A greater number (50.5%) are age 65 or over and already at risk for falls and fractures. (Reference Table 8.1.4 PDF [20] CSV [21])

In 1996-1998, 23.4 million persons reported a musculoskeletal injury, while 26.3 million reported such an injury in 2012-2014. The prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries remained relatively constant at 8.6% and 8.3% of the population in the two three-year periods, respectively. Age distribution of injuries may explain why the prevalence has not increased. About half of injuries occur among persons younger than 45 years, a population segment growing more slowly than those who are older. It is possible improvements in the safety of automobiles and other public health prevention activities have also played a role. Although the MEPS reporting of musculoskeletal injury trends supports trend data previously reported, the overall prevalence is substantially lower than the 40.8 million injury treatment episodes reported in the Injuries section of this report. Injury treatment episodes include total cases treated in doctors' offices, outpatient clinics, emergency rooms, and inpatient admissions in 2010. (Reference Table 8.1.5 PDF [22] CSV [23])

Using the more expansive definition of musculoskeletal diseases, in 2012-2014, 93.6 million persons (versus 34.9 million using the more conservative definition) reported one or more spine conditions and 69.0 million (versus 65.6 million) reported arthritis and joint pain. The base and expansive definitions for osteoporosis are identical, so the number of cases for both definitions are also identical, but substantially lower than reported in the Osteoporosis section of this report, as previously noted. The number reporting musculoskeletal injuries was slightly higher than in the more conservative definition (30.3 versus 26.3 million). The increased prevalence in the “other” musculoskeletal diseases category was also substantial, with 75.1 million in the expansive definition versus 19.4 million. (Reference Table A8.1.2 PDF [24] CSV [25]; Table A8.1.3 PDF [26] CSV [27]; Table A8.1.4 PDF [28] CSV [29]; Table A8.1.5 PDF [30] CSV [31]; and Table A8.1.6 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Musculoskeletal healthcare utilization is examined for the MEPS for the following types of care: ambulatory physician visits, ambulatory non-physician visits, prescription medications filled, home health care days, and hospital discharges for all musculoskeletal conditions and by type of condition.

Over the annual 3-year average periods, 1996-1998 to 2012-2014, for which the MEPS data is analyzed, ambulatory non-physician care visits show the greatest increase, both in share (%) of population reporting such a visit and in total visits. While the proportion of the population with a prescription filled remained steady at just over 80%, prescription medications filled increased in total number due to population increases and the rise in mean number of prescriptions filled. The total number of prescriptions filled showed an average annual increase of 7.5%, while the mean number of prescriptions filled showed an annual increase of 3.5%. Ambulatory physician visits and hospital discharges both increased by 2.6% annually over the seventeen-year period from 1996-1998 through 2012-2014. (Reference Table 8.2.1 PDF [34] CSV [35])

Persons with musculoskeletal diseases account for a large and growing share of healthcare utilization. In any given year, about 85% of persons with musculoskeletal diseases have at least one ambulatory care visit to a physician's office, averaging just under six such visits per year. Between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014, ambulatory physician visits for these individuals increased from 425.5 million to 602.3 million. Growth in the number of persons with musculoskeletal diseases, rather than an increase in the number of visits by individuals, is primarily responsible for this increase.

In contrast to the relatively stable number of physician office visits per person with a musculoskeletal condition, there was an increase in the proportion of the US population with visits to ambulatory providers other than physicians. The average number of visits to non-physician providers by persons with musculoskeletal diseases also increased. Non-physician ambulatory healthcare providers include physical therapists, occupational therapists, chiropractors, social workers, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other related healthcare workers. In 1996-1998, approximately 40% of persons with musculoskeletal diseases visited a non-physician healthcare provider at least once; by 2012-2014, the proportion had jumped to 58.0%. At the same time, the average number of such visits increased from 2.6 per person to 4.5. The result was more than a doubling, from 197.5 million to 484.0 million, in total non-physician ambulatory care visits between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014.

During this same time frame of 1996-1998 through 2012-2014, the use of prescription medications among persons with musculoskeletal diseases rose substantially. While the proportion of persons with a musculoskeletal disease who filled at least one prescription ranged 81% to 84% over the 17-year period, the mean number of prescriptions filled per person steadily increased from 13.1 to 20.4 mean fills. The result was a more than doubling, from 995.3 million in 1996-1998 to nearly 2.2 billion in 2012-2014, in the number of prescription medications filled by persons with a musculoskeletal disease.

Despite widespread concerns that an aging population would use an increasing amount of home health care, there is no evidence that this is occurring. Both the proportion of persons with a musculoskeletal disease using home health care and the average number of home health care visits remained low with little change over the 1996-1998 through 2012-2014 period. Only 5.5% of persons reported any home health care visits in 2012-2014, with an average of 3.7 visits. The total number of home health care visits to persons with a musculoskeletal disease rose from 296.3 million to 397.9 million, entirely due to population increase.

An increase of more than 40%, from 15.2 to 21.5 million, in the number of hospital discharges for persons with a musculoskeletal disease occurred in the periods 1996-1998 to 2012-2014. This may be due to the aging population. The percentage of persons with a musculoskeletal disease who were hospitalized one or more times in a year was roughly stable, with 11% to 12% of persons with these conditions hospitalized annually in 1996-1998 to 2012-2014 period. The average number of hospitalizations per person, at 0.2, did not change.

Using the more expansive definition of musculoskeletal diseases, in 2012-2014 there were an estimated 812.1 million visits to physicians among persons with these diseases, as well as 584.7 million ambulatory visits to providers other than physicians, 2.9 billion prescriptions filled, 503.5 million home care visits, and 16.2 million hospital discharges. It should be noted that in this expansive definition, the number of ambulatory visits per person to providers other than physicians and the number of medications per person has risen dramatically. (Reference Table A8.2 PDF [38] CSV [39])

Healthcare utilization by musculoskeletal conditions shows some variation from total musculoskeletal conditions. Arthritis and joint pain accounted for a substantial share of growth in healthcare utilization of all types. The rate of increase for all sources of health care utilized by persons with arthritis was two to three times the rate increase for all musculoskeletal conditions. Osteoporosis accounted for much of the limited growth in home health care visits, increasing 133% over the 17-year analysis period compared with a 34% overall increase. Growth in healthcare visits for injuries was slower than overall musculoskeletal conditions, while healthcare visit growth rates for spine diseases were about even.

Detailed data related to utilization by condition can be found in specific condition data tables and is also discussed under the condition section. See spine (Reference Table 8.2.2 PDF [42] CSV [43]); arthritis and joint pain (Reference Table 8.2.3 PDF [44] CSV [45]); osteoporosis (Reference Table 8.2.4 PDF [46] CSV [47]); injuries (Reference Table 8.2.5 PDF [48] CSV [49]); other musculoskeletal conditions (Reference Table 8.2.6 PDF [50] CSV [51]); and summary (Reference Table 8.3 PDF [52] CSV [53]).

Musculoskeletal medical care expenditures are presented in two ways: (1) for all persons with a musculoskeletal disease, regardless of whether the musculoskeletal disease was the reason for the expenditure (total direct cost), and (2) as a measure of the expenditures beyond those expected for persons of similar characteristics but who do not have a musculoskeletal disease (incremental cost). Incremental cost is that share of cost estimated to be directly related to the musculoskeletal condition. Both total and incremental costs are expressed as the average cost per person with a musculoskeletal disease and as the aggregate cost (sum) for all persons with a musculoskeletal disease.

Mean costs are presented for ambulatory care, inpatient care, prescription costs, and a residual for other costs, as well as the total cost. Medical care costs are expressed in both the current year dollars (i.e., the year the data was collected) and in 2014 dollars to provide a standard of comparison across years.

Total direct and incremental costs for all musculoskeletal conditions and five subconditions are summarized in Table 8.6.1. (PDF [54] CSV [55])

Overall, total average direct expenditures for persons with musculoskeletal diseases increased from $5,020 in 1996-1998 to $8,206 in 2012-2014, in 2014 dollars, a more than 60% increase. Ambulatory care was the largest cost share and accounted for 34% of total average per person costs for musculoskeletal diseases in 2012-2014.

Over the 1996-1998 through 2012-2014 periods, the share of total costs associated with ambulatory care rose slightly, from 31 to 34%, while the share for inpatient care declined from 36% to 27%. The share for the residual category also declined, from 18% to 15% of the total. However, medication costs accounted for a far larger share, increasing from 14% to 24% of the total. In 2014 dollars, the average amount spent for medications increased from $691 in 1996-1998 to $1,967 in 2012-2014, or nearly tripled in relative terms. (Reference Table 8.4.1 PDF [56] CSV [57])

In 2012-2014, incremental expenditures for musculoskeletal diseases averaged $1,510 in 2014 dollars. (Reference Table 8.5.1 PDF [60] CSV [61])

Data for specific musculoskeletal conditions has been analyzed through the 2012-2014 time period, and shown in 2014 dollars. Total per person direct medical care expenditures rose for each of the major subconditions between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014. Expenditures for arthritis and joint pain, which rose from $6,642 to $9,554, and osteoporosis, which rose from $8,906 to $12,869 per person, had the smallest relative increases at 44% each, although both conditions had high average per person costs. Costs for spine conditions rose by 80%, from $5,023 to $9,035; for injuries by 93%, from $4,211 to $8,135; and for other musculoskeletal conditions by 62%, from $6,799 to $11,047.

Detailed data related to per person all-cause direct cost by condition can be found in specific condition data tables and is also discussed under the condition section. See spine (Reference Table 8.4.2 PDF [64] CSV [65]); arthritis and joint pain (Reference Table 8.4.3 PDF [66] CSV [67]); osteoporosis (Reference Table 8.4.4 PDF [68] CSV [69]); injuries (Reference Table 8.4.5 PDF [70] CSV [71]); other musculoskeletal conditions (Reference Table 8.4.6 PDF [72] CSV [73]); and summary (Reference Table 8.7 PDF [74] CSV [75]).

Except for arthritis and joint pain, incremental direct costs by condition grew more slowly than all-cause direct costs. This is likely due to co-morbid conditions which may have a higher healthcare cost than some musculoskeletal diseases. In general, groups of individuals with more expensive conditions who also are older and have more comorbid conditions will have higher per-person all-cause costs, while incremental costs are those attributable to the condition and less affected by age, other demographics, or comorbid conditions.

Detailed data related to per person incremental direct cost by condition can be found in specific condition data tables and are also discussed under the condition section. See spine (Reference Table 8.5.2 PDF [78] CSV [79]); arthritis and joint pain (Reference Table 8.5.3 PDF [80] CSV [81]); osteoporosis (Reference Table 8.5.4 PDF [82] CSV [83]); injuries (Reference Table 8.5.5 PDF [84] CSV [85]); other musculoskeletal conditions (Reference Table 8.5.6 PDF [86] CSV [87]); and summary (Reference Table 8.7 PDF [74] CSV [75]).

Expenditures for musculoskeletal diseases did not differ substantially by gender and education level in 2015. On an unadjusted basis, women with musculoskeletal diseases had only 3% higher per person average expenditures than men. On the other hand, Hispanics report substantially lower annual per person expenditures than the other race and ethnic groups, for example 40% lower than non-Hispanic whites. Individuals who were married or with partners or who were widowed, separated, or divorced had higher annual per person expenditures than those who were never married, probably due, in part, to age differences.

Lack of insurance had the most profound impact on average health expenditures for persons with musculoskeletal conditions. Average per person expenditures on behalf of those without insurance, at $4,065, were about 40% as high as those with public insurance (i.e., Medicaid/Medicare), at $10,564, and about half that of those with private insurance, at $7,967. Again, some of this difference may be due to age, as young people are more likely to be uninsured than older people, but a portion is also due to lack of healthcare resources. Thus, lack of health insurance is inconsistent with the belief that persons who lack insurance are somehow able to obtain care. (Reference Table 8.8 PDF [88] CSV [89])

Aging is strongly correlated with increased per person all-cause medical expenditures for persons with a musculoskeletal disease along with other co-morbid conditions, but not necessarily so when attributed directly to musculoskeletal diseases (incremental cost).

Per person all-cause expenditures in 2012-2014 for persons 65 years of age or older, at a mean of $11,760, were about 2½ times the mean per person costs for those under the age of 45.Persons aged 45 to 64 years had mean per person healthcare expenditures at around 75% that of the oldest population.

On the other hand, per person incremental costs in 2012-2014 were highest among those under age 18 and lowest among those 65 or over. Since this incremental cost is the estimate directly attributed to musculoskeletal conditions, the reversal may reflect the fact that young persons are less likely to have co-morbid conditions, and when they do have a musculoskeletal disease, it accounts for a greater proportion of medical care. Conversely, those aged 65 or over are more likely to have multiple co-morbid conditions, reducing the share of cost attributed to the musculoskeletal condition(s). (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [92] CSV [93]).

Aggregate all-cause expenditures in 2014 dollars increased from $381.4 billion in 1996-1998 to $882.5 billion in 2012-2014, an increase of more than 130%. (Reference Table 8.6.1 PDF [54] CSV [55]) In 1996-1998, aggregate all-cause expenditures for persons with a musculoskeletal disease, whether for musculoskeletal disease or other conditions, represented 3.2% of the GDP. By 2012-2014, the proportion had grown to 5.2% of the GDP. (Reference Table 8.14 PDF [96] CSV [97])

Aggregate incremental expenditures in 2014 dollars increased from $101.1 billion in 1996-1998 to $162.4 billion in 2012-2014, increasing from 0.25% to 0.57% of the GDP. (Reference Table 8.6.1 PDF [54] CSV [55]; Table 8.14 PDF [96] CSV [97])

Over the full-time range of 1996-1998 through 2012-2014, the annual average rate of increase in aggregate all-cause and incremental costs for musculoskeletal diseases has been 8.2% and 3.8%, respectively. (Reference Table 8.7 PDF [74] CSV [75])

Because of the higher prevalence and relatively high level of expenditures per person, aggregate all-cause expenditures have consistently been greatest for arthritis and joint pain, accounting for $626.8 billion in healthcare costs in 2012-2014. Spine conditions, with an estimated $315.4 billion aggregate cost in 2012-2014, are the second most expensive musculoskeletal healthcare condition. Aggregate costs for injuries and other musculoskeletal conditions were $213.7 and $214.8 billion, respectively, in 2012-2014. Osteoporosis, with $73.6 billion, accounted for the lowest aggregate of all costs. Totals for subconditions, when summed, exceed the overall total due to the potential for persons to be included in more than one condition group.

Sampling variability limits inference about time trends in incremental expenditures associated with the subcondition groups. However, while estimates do not have the same precision as those for all musculoskeletal diseases, it is fair to conclude that 2012-2014 aggregate incremental expenditures, at $88.7 billion, were largest for arthritis and joint pain. Further, aggregate incremental expenditures have increased substantially since 1996-1998 for all subcondition groups. (Reference Columns D and F, Table 8.6.2 PDF [100] CSV [101]; Table 8.6.3 PDF [102] CSV [103]; Table 8.6.4 PDF [104] CSV [105]; Table 8.6.5 PDF [106] CSV [107]; Table 8.6.6 PDF [108] CSV [109])

Unlike other tables on economic costs of musculoskeletal conditions that use an average of three years of data for sequential years, analysis based on demographic characteristics uses a single year, resulting in 2014 costs that are somewhat different than those for 2012-2014.

In 2014, aggregate all-cause expenditures for musculoskeletal conditions totaled $919.4 billion, slightly higher than the 2012-2014 total. Because per person all-cause expenditures were lower among those without insurance ($4,065), aggregate expenditures on behalf of the approximately 7.1 million without insurance were only $29.0 billion; the bulk of the aggregate expenditures occurred among the 71.4 million with private insurance ($568.9 billion) or the 30.4 million with public insurance ($321.5 billion).

Of the almost 109 million persons with musculoskeletal diseases in 2014, 46.3 million (42.5%) reported a limitation in functioning, work, housework, or school, or had a limitation in vision and hearing. Such persons incurred aggregate all-cause expenditures of $636.0 billion, or 69.2% of all aggregate expenditures for musculoskeletal diseases. Slightly fewer (about 26 million, 23.8% of persons with musculoskeletal diseases) reported only limitation in work, housework, or school; such persons incurred $446.4 billion, or 48.6% of all-cause aggregate expenditures for these conditions. (Reference Table 8.8 PDF [88] CSV [89])

Aggregate costs by age group generally reflect the trends previously described in per person expenditures [114], except for total all-cause aggregate costs. Although persons aged 65 and over had the highest mean per person cost, persons aged 45-64 accounted for the largest share of aggregate costs due to the large size of this cohort. (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [92] CSV [93])

The total economic impact of musculoskeletal diseases includes two types of costs: costs to treat individuals (direct medical costs) and costs paid indirectly by these individuals and society (lost wages).

Aggregate all-cause costs among persons with a musculoskeletal disease, including direct healthcare costs plus decreased or lost wages (indirect cost), was estimated to be $980.1 billion per year in 2012-2014. (Reference Table 8.14 PDF [96] CSV [97]). Aggregate incremental costs (i.e., those attributed to musculoskeletal disease) for direct and indirect costs sum to a $321.6 billion per year Tables 8.6.1 and 8.12). In other words, direct and indirect costs attributable to musculoskeletal disease account for a third of all-cause direct and indirect costs for this population.

Between the years 1996-1998 and 2012-2014, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)1, in constant 2014 dollars, has risen from $12.0 trillion to $17.0 trillion, an increase of 42%. Over the same two time frames, total direct and indirect costs of musculoskeletal conditions rose from $411.9 billion to $980.1 billion. This is an increase of 138%, or more than three times the rate of increase for the GDP.

As a share of GDP, using the same 2014 dollars base, total direct and indirect costs for musculoskeletal conditions increased by 68%, from 3.44% to 5.76%. Indirect costs rose twice as fast as direct costs in relative terms. However, indirect cost are a much smaller share of total cost than direct costs, constituting 0.25% of GDP in 1996-1998 and 0.57% in 2012-2014. Direct costs rose from a 3.18% share to a 5.19% share over the same time period. (Reference Table 8.14 PDF [96] CSV [97])

Musculoskeletal diseases affect the US economy through direct medical costs and through lost wages. Changes in the organization of medical care, new methods of treatment, new drugs, and rising prices for existing services and medications, as well as changes in the employment situation of persons with musculoskeletal diseases, all affect the economic impact these diseases have on the economy. The result is a major economic burden from musculoskeletal diseases.

Over the period 1996-1998 through 2012-2014, the share of per person all-cause direct costs for musculoskeletal diseases shifted between healthcare sources only slightly. Ambulatory care and prescription drugs both increased in share of total cost, while inpatient and residual care both decreased. The change in mean per person costs followed a similar pattern. Although costs increased for all care sources, it was greatest for prescription and ambulatory care costs.

The share of musculoskeletal healthcare costs devoted to prescription medications increased the most, growing by more than 70%, from 14% to 24% of total cost. Computed in 2014 dollars, the mean annual prescription cost per person increased approximately 185%, from $691 to $1,967. During this time, development of biologic agents for several inflammatory conditions, particularly rheumatoid arthritis, occurred, as well as the widespread use of the cox-2 inhibitors (coxibs) for musculoskeletal pain, and may have accounted for some of the rapid increase. (Reference Table 8.4.1 PDF [56] CSV [57])

The importance of prescription drugs is not confined to just all-cause expenditures. In 2014 dollars, the increment in musculoskeletal diseases costs associated with prescription drugs rose even faster, increasing from a mean of $149 per person in 1996-1998 to a mean of $435 in 2012-2014, an increase of nearly 200%. (Reference Table 8.5.1 PDF [60] CSV [61]).

The amount of all-cause indirect costs associated with wage losses among persons with musculoskeletal conditions fluctuated from a low of $628 per person with a work history in 1996-1998 to a high of $2,400 per person in 2003-2005, and was $1,490 per person as of 2012-2014. The increment in wage losses, however, has risen steadily over time, from $999 per person in 1996-1998 to about $2,500 per person in the three most recent three-year time periods. The latter finding suggests that persons with musculoskeletal conditions experience a greater loss of wages than would be expected based on their characteristics other than work history.

In 1996-1998, about 48.5 million persons with a musculoskeletal disease had established a work history. On average, these individuals earned $628 in 2014 dollars less than those without musculoskeletal conditions; their earnings losses aggregated to $30.5 billion. By 2012-2014, the number of persons with musculoskeletal diseases and a work history had grown to about 65.5 million. On average, these workers had earnings losses of $1,490 each, resulting in aggregate all-cause earnings losses of $97.5 billion. The $67 billion increase in aggregate indirect costs of lost wages was the result of growing population numbers with musculoskeletal disease and increases in wages.

Estimates of incremental indirect costs grew from an aggregate of $48.5 billion in 1996-1998 to $159.2 billion in 2012-2014. While the rate of growth was similar for both, actual costs associated with musculoskeletal diseases is much greater. This highlights the extent to which persons with musculoskeletal disease characteristics earn less than would be expected of persons with similar characteristics but no musculoskeletal disease. (Reference Table 8.12 PDF [122] CSV [123])

The following section looks at specific musculoskeletal disease conditions to provide broad estimates of costs associated with them. However, it should be noted that medical conditions in MEPS are self-reported, and may result in misreporting, and, thus, misrepresentation, of some conditions. An additional issue is that estimates for the prevalence and impact of specific conditions may differ year to year due to small sample sizes and the inherent variability that results. To improve the reliability for specific conditions, including gout, osteoarthritis and related disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, and other and unspecified disorders of the back, estimates are based on a merging of MEPS data from the most recent seven years, 2008-2014. In this edition, we also make estimates of direct costs associated with connective tissue disease, the most common of which is systemic lupus erythematosus.

As noted previously, the average all-cause expenditures for persons with all forms of musculoskeletal disease averaged $8,206 in 2012-2014. (Reference Table 8.4.1 PDF [56] CSV [57])

Over the period, 2008-2014, slightly more than 3 million persons self-reported gout, about 32.5 million reported osteoarthritis and related disorders, 1.7 million reported rheumatoid arthritis, and 19.4 million reported other and unspecified disorders of the back. All-cause medical care expenditures averaged $11,936 for persons with gout, $11,502 for those with osteoarthritis and related disorders, $19,040 for those with rheumatoid arthritis, and $8,622 for those with back disorders. Thus, for all conditions other than back disorders, all-cause expenditures were much larger than the average among all persons with musculoskeletal disorders. (Reference Table 8.13 PDF [126] CSV [127])

Over the period 2008-2014, about 800,000 persons self-reported connective tissue disorders. Persons with connective tissue disorders averaged $19,702 in all-cause expenditures, similar to the average among those with rheumatoid arthritis. The magnitude of the all-cause expenditures would appear to be affected by insurance status and region of the country. For the former, those with public insurance had higher average expenditures, $29,579, than those with private insurance, $16,003, probably reflecting the older age and greater severity of disease among the former. Those with no insurance had all-cause expenditures of only $5,631, indicating that their care may be systematically different in scope. Such expenditures were much higher for those in the Northeast ($27,349) or West ($26,210) than in the Midwest ($11,821) or South ($14,741). Expenditures for ambulatory care accounted for 40% of the total in the Northeast region, while inpatient care accounted for 45% in the West region. Prescription costs were highest in the Midwest, accounting for 44% of total. These numbers indicate differences in care strategies for connective tissue disorders across the country. Age and education may also be factors in care strategies, with older and the highest educated persons using ambulatory care more, while younger persons and those with less than a college degree use inpatient care more. (Reference Table 8.19 PDF [130] CSV [131]; Table 8.20 PDF [132] CSV [133]; Table 8.21 PDF [134] CSV [135])

Additional discussion on the burden of select musculoskeletal diseases can be found in condition chapters. To jump to these discussions, click on the conditions listed below.

Connective Tissue Disorders [138]

Gout [139]

Rheumatoid Arthritis [140]

Osteoarthritis [141]

Other and Unspecified Disorders of the Back [142]

The aging of the population has increased the prevalence and the share of persons with musculoskeletal conditions in older age groups, as well as healthcare expenditures. In 1996-1998, an average of just under 22 million persons aged 45 to 64 years reported a musculoskeletal condition, while about 16.5 million of those aged 65 years and older did so. By 2012-2014, these numbers had increased to just under 41 million and just under 28 million, respectively. The share of persons with musculoskeletal conditions among persons aged 45 to 64 years increased from 29% in 1996-1998 to 38% in 2012-2014, and increased from 22% to 26% among those aged 65 years and older. Most of this shift is due to the impact of aging and population growth, as prevalence rates have remained relatively steady for at least the last five years. (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [92] CSV [93])

All-cause aggregate medical care expenditures among persons with musculoskeletal conditions have risen substantially due to population aging as well as the general increase in medical care costs. In 2014 dollars, total aggregate expenditures increased between 1996-1998 and 2012-2014 among persons aged 45 to 64 years from $115 billion to just under $369 billion, while they increased among those aged 65 years and older from $159 billion to $327 billion during this time. Although all-cause per person costs increase with age, the magnitude of the increase was greater in relative terms among persons aged 45 to 64 years with musculoskeletal conditions (from $5,276 to $9,057, or by about 72%) than among such persons aged 65 years and older (from $9,648 to $11,760, or by 22%), but was highest for the under 18 age group. Although the data do not address why the costs rose faster among those aged 45-64, the faster increase may be the result of greater cost controls in Medicare, which serves people aged 65 or older, or to subtle discrimination against older persons in the types of treatments offered. (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [92] CSV [93])

In this updated edition of the Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the U.S., data are presented on the prevalence and impact of this group of conditions among children. In 2012-2014, among the 77.4 million children and adolescents in the U.S. (those aged less than 18 years of age), an estimated 8.3 million had a musculoskeletal condition, 10.7% of all children. (Reference Table 8.16 PDF [147] CSV [148])

Most (85.2%) of the children with musculoskeletal conditions had ambulatory visits totaling more than 31 million visits, or just under an average of four per child for all children with a musculoskeletal disease. Although a smaller proportion of children had visits to non-physician providers they made more visits and the average was 3.5 visits for all children with a musculoskeletal disease, resulting in almost as many visits to these providers, more than 29 million. Children with musculoskeletal conditions averaged more than four prescriptions filled per year, or just under 37 million in total. Very few (1.4%) had one or more home health care visits, but because the average was spread over the 8.3 million with any condition, the number of home health visits for the few having them approached 70 visits. Only 1 in 25 children (4.1%) were discharged from the hospital. Nevertheless, the 8.3 million children with musculoskeletal conditions had 410,000 hospital discharges. (Reference Table 8.17 PDF [149] CSV [150])

All-cause medical care costs among children with musculoskeletal diseases, at $4,504 per child in 2012-2014, were less than among older persons with these conditions, but still amounted to more than $37 billion in the aggregate. Incremental medical care costs were higher among children, at $2,381 per child, than among those older, presumably because most children experience very low costs but those with musculoskeletal conditions are an exception to that rule. In aggregate, incremental costs among children with musculoskeletal conditions amounted to just under $20 billion a year in 2012-2014. (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [92] CSV [93])

All-cause medical care costs among children in 2012-2014 were higher among boys than girls ($5,411 vs. $3,550 per child per year) but did not differ dramatically by race/ethnicity. Children with these conditions who lacked health insurance had far lower all-cause medical care costs per year ($1,173) than those with private ($4,834) or public insurance ($3,994). (Reference Table 8.18 PDF [151] CSV [152])

This edition of the Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States continues to use condition codes defined in ICD-9-CM based on 2014 data. The earliest data based on ICD-10-CM codes will be 2016, with a one to two-year lag in availability. Codes used in the economic impact analysis by musculoskeletal diseases fall into the two categories of base codes and expansive codes.

Conditions included in the base musculoskeletal disease rubric include spine conditions, arthritis and joint pain, the category that includes osteoporosis (other diseases of bone and cartilage), injuries, and an inclusive “other” category for the remaining conditions. Conditions selected for the cost analysis presented are based on condition topics included in this site. Data are reported primarily for base case ICD-9-CM codes, or those codes for which musculoskeletal disease is the principal cause of the condition rather than a consequence of another major health condition (e.g., bone cancer metastases from an other primary cancer site).

Estimates are also provided for a more expansive list of codes of musculoskeletal-related diseases that include conditions for which musculoskeletal diseases are either the primary and secondary cause of the condition. This more expansive list of conditions yields a vastly larger prevalence estimate than the base case list. However, it is reasonable to assume the cost of musculoskeletal diseases probably exceeds the conservative estimates presented here. For example, a person with bone metastases would incur costs to treat the bone manifestation, even though the cancer, not the bone condition, is the primary etiology.

ICD-9-CM codes included in each subcategory for the base and expansive conditions are listed in subsections.

Spine

Special Symptoms or Syndromes, NEC : 307

Migraine : 346

Trigeminal Nerve Disorders : 350

Nerve Root and Plexus Disorders : 353

Dentofacial Anomalies, Including Malocclusion : 524

Pain and Other Symptoms Associated with Female Genital organs : 625

Menopausal and Postmenopausal Disorders : 627

General Symptoms : 780

Symptoms Involving Skin and Other Integumentary Tissue : 782

Symptoms Involving Head and Neck : 784

Symptoms Involving Respiratory System and Other Chest Symptoms : 786

Symptoms Involving Digestive System : 787

Other Symptoms Involving Abdomen and Pelvis : 789

Injury to Other Cranial Nerve(s) : 951

Injury to Nerve Roots and Spinal Plexus : 953

Arthritis and Joint Pain

Gonococcal Infections : 098

Other Venereal Diseases : 099

Other and Unspecified Infectious and Parasitic Diseases : 136

Other and Unspecified Disorders of Metabolism : 277

Purpura and Other Hemorrhagic Conditions : 287

Other Paralytic Syndromes : 344

Mononeuritis of Upper Limb and Mononeuritis Multiplex : 354

Inflammatory and Toxic Neuropathy : 357

Other and Ill-defined Cerebrovascular Disease : 437

Other Peripheral Vascular Disease : 443

Polyarteritis Nodosa and Allied Conditions : 446

Other Disorders of Arteries and Arterioles : 447

Psoriasis and Similar Disorders : 696

Osteoporosis

Other Disorders of Bone and Cartilage : 733

Musculoskeletal Injuries

Open Wound of Neck : 874

Open Wound of Other and Unspecified Sites, Except Limbs : 879

Contusion of Trunk : 922

Contusion of Upper Limb : 923

Contusion of Lower Limb and of Other and Unspecified Sites : 924

Crushing Injury of Trunk : 926

Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Other Salmonella Infections : 3

Rat-bite Fever : 26

Meningococcal Infection : 36

Rubella : 56

Other Arthropod-borne Diseases : 88

Early Syphilis, Symptomatic : 91

Other forms of Late Syphilis, with Symptoms : 95

Yaws : 102

Late Effects of Tuberculosis : 137

Malignant Neoplasm of Other and Ill-defined Sites : 195

Secondary Malignant Neoplasm of Other Specified Sites : 198

Other Malignant Neoplasms of Lymphoid and Histiocytic Tissue : 202

Multiple Myeloma and Immunoproliferative Neoplasms : 203

Other Benign Neoplasm of Connective and Other Soft Tissue : 215

Neoplasm of Uncertain Behavior of Other and Unspecified Sites and Tissues : 238

Neoplasms of Unspecified Nature : 239

Disorders of Parathyroid Gland : 252

Disorders of Lipoid Metabolism : 272

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism : 275

Hereditary Hemolytic Anemias : 282

Organic Sleep Disorders : 327

Mononeuritis of Lower Limb and Unspecified Site : 355

Peritonitis and Retroperitoneal Infections : 567

Other Cellulitis and Abscess : 682

Other and Unspecified Congenital Anomalies : 759

Late Effects of Injuries to Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues : 906

Certain Early Complications of Trauma : 958

Complications Peculiar to Certain Specified Procedures : 996

Personal History of Other Diseases : V13

Organ or Tissue Replaced By Transplant : V42

Organ or Tissue Replaced By Other Means : V43

Other Postprocedural States : V45

Problems with Head, Neck, and Trunk : V48

Fitting and Adjustment of Other Device : V53

Convalescence and Palliative Care : V66

Follow-up Examination : V67

Special Screening Examination for Bacterial and Spirochetal Diseases : V74

Spine

Special Symptoms or Syndromes, NEC : 307

Migraine : 346

Trigeminal Nerve Disorders : 350

Nerve Root and Plexus Disorders : 353

Dentofacial Anomalies, Including Malocclusion : 524

Pain and Other Symptoms Associated with Female Genital Organs : 625

Menopausal and Postmenopausal Disorders : 627

General Symptoms : 780

Symptoms Involving Skin and Other Integumentary Tissue : 782

Symptoms Involving Head and Neck : 784

Symptoms Involving Respiratory System and Other Chest Symptoms : 786

Symptoms Involving Digestive System : 787

Other Symptoms Involving Abdomen and Pelvis : 789

Injury to Other Cranial Nerve(s) : 951

Injury to Nerve Roots and Spinal Plexus : 953

Arthritis and Joint Pain

Gonococcal Infections : 098

Other Venereal Diseases : 099

Other and Unspecified Infectious and Parasitic Diseases : 136

Other and Unspecified Disorders of Metabolism : 277

Purpura and Other Hemorrhagic Conditions : 287

Other Paralytic Syndromes : 344

Mononeuritis of Upper Limb and Mononeuritis Multiplex : 354

Inflammatory and Toxic Neuropathy : 357

Other and Ill-defined Cerebrovascular Disease : 437

Other Peripheral Vascular Disease : 443

Polyarteritis Nodosa and Allied Conditions : 446

Other Disorders of Arteries and Arterioles : 447

Psoriasis and Similar Disorders : 696

Osteoporosis

Due to small sample sizes, no additional codes were included in the expansive analysis

Musculoskeletal Injuries

Open Wound of Neck : 874

Open Wound of Other and Unspecified Sites, Except Limbs : 879

Contusion of Trunk : 922

Contusion of Upper Limb : 923

Contusion of Lower Limb and of Other and Unspecified Sites : 924

Crushing Injury of Trunk : 926

Other Musculoskeletal Conditions

Other Salmonella Infections : 3

Rat-bite Fever : 26

Meningococcal Infection : 36

Rubella : 56

Other Arthropod-borne Diseases : 88

Early Syphilis, Symptomatic : 91

Other forms of Late Syphilis, with Symptoms : 95

Yaws : 102

Late Effects of Tuberculosis : 137

Malignant Neoplasm of Other and Ill-defined Sites : 195

Secondary Malignant Neoplasm of Other Specified Sites : 198

Other Malignant Neoplasms of Lymphoid and Histiocytic Tissue : 202

Multiple Myeloma and Immunoproliferative Neoplasms : 203

Other Benign Neoplasm of Connective and Other Soft Tissue : 215

Neoplasm of Uncertain Behavior of Other and Unspecified Sites and Tissues : 238

Neoplasms of Unspecified Nature : 239

Disorders of Parathyroid Gland : 252

Disorders of Lipoid Metabolism : 272

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism : 275

Hereditary Hemolytic Anemias : 282

Organic Sleep Disorders : 327

Mononeuritis of Lower Limb and Unspecified Site : 355

Peritonitis and Retroperitoneal Infections : 567

Other Cellulitis and Abscess : 682

Other and Unspecified Congenital Anomalies : 759

Late Effects of Injuries to Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues : 906

Certain Early Complications of Trauma : 958

Complications Peculiar to Certain Specified Procedures : 996

Personal History of Other Diseases : V13

Organ or Tissue Replaced By Transplant : V42

Organ or Tissue Replaced By Other Means : V43

Other Postprocedural States : V45

Problems with Head, Neck, and Trunk : V48

Fitting and Adjustment of Other Device : V53

Convalescence and Palliative Care : V66

Follow-up Examination : V67

Special Screening Examination for Bacterial and Spirochetal Diseases : V74

Arthritis and Spine Conditions

Gout : 274

Osteoarthritis and Allied Diseases : 714, priority nonRA with self-report of 716 or 719

Rheumatoid Arthritis : 714 and priority RA

Other/Unspecified Disorders of the Back : 724

Connective Tissue Disease : 710.9

Additional data on costs can be found directly in the data tables associated with this chapter. Due to limited variability, small samples, and the desire to highlight primary key findings, not all data in the tables is discussed. In addition, data on specific conditions (spine, arthritis and related conditions, osteoporosis, and injuries), as well as the child and adolescent section, are discussed within the pages relative to each condition or population.

The two tables below will help identify specific Economic Cost tables that contain data of interest. To enlarge it, click on the table of interest. To download the Tables by Title and File click here [155]. To download the Tables by Title and Content, click here [156].

To view all musculoskeletal data tables, select the Tables tab at the top of any page in this section. PDF and CSV files of all tables in the Economic Cost section also can be downloaded in a zip file from the Tables tab.

Economic cost for musculoskeletal-related health care diseases presented in this book are based on data from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) using a methodology developed by the principal author and colleagues at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC).1,2,3,4,5 The MEPS is a comprehensive data source designed for cost of illness studies.6,7,8,9 The MEPS uses a complex multistage probability sample of the U.S. population and annually queries this sample three times about their medical conditions, health care utilization, and employment status, and provides information on the charges and expenditures associated with medical utilization. The authors use expenditure information to produce two types of cost estimates. The first, total cost, is an indication of all medical care costs and earnings losses incurred by persons with a musculoskeletal disease, regardless of the condition for which the cost was incurred. The second, incremental cost, is an estimate of the magnitude of cost that would be incurred beyond those experienced by persons of similar demographic and health characteristics but who do not have one or more musculoskeletal disease. Cost estimates are produced as the mean per person medical care cost and as the aggregate, or sum of mean costs overall, associated with all persons with musculoskeletal diseases.

Early editions of this book based estimates of the economic impact of musculoskeletal diseases on the Rice cost of illness methodology.10,11 The Rice model utilized the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) and other available national health care data sources, such as the National Health Interview Survey.12 All costs associated with hospitalizations or treatments for persons with a musculoskeletal disease listed as the primary, or 1st, diagnosis were included in the model. The Rice model defines direct cost as those associated with all components of medical care (i.e., inpatient and outpatient care, medications, devices, and costs associated with procuring medical care), and indirect cost as those associated with wage loss due to morbidity or mortality, plus an estimate of intangible costs.

In the Rice model, mortality accounted for 7% of total indirect medical cost for all conditions. The MEPS data do not provide a comparable method for calculating wage loss associated with mortality. Hence, total cost presented here represents an under count by a similar percentage. Because musculoskeletal diseases have a smaller impact on mortality than most other major categories of illness, the under count will be an unknown, but smaller, percentage.

Comparing total cost for 1995, the last year that Rice updated her estimates,11 updated to 1996 terms, the first year for which MEPS data is available, and omitting cost associated with mortality, the current analysis results in $207 billion in total cost associated with musculoskeletal diseases using the Rice method and about $143 billion using the MEPS database. The difference may be due to allocating a higher proportion of diagnoses to the musculoskeletal classification in the Rice study. The difference suggests that inferring time changes between the Rice studies and those using MEPS should be done with caution.

A series of papers provide a detailed description of the methods of estimating total and incremental direct and indirect cost of conditions, and outline the regression model used to adjust for differences of persons with and without musculoskeletal diseases due to demographic characteristics and health status.2,4 As in our previous work, we applied a two-stage model to estimate musculoskeletal condition-attributable costs for ambulatory, inpatient, prescription, and other expenditures, and a four-stage model for overall expenditures. However, the present analysis differs from prior analysis due to the use of a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and a log-link, as opposed to a log transformation with a smearing estimate applied to back-transformed predicted values, in the stages predicting costs among individuals with any positive expenditures.

Although generally, prevalence and cost associated with musculoskeletal diseases increase over time, sampling variability in the MEPS does not reflect this in each successive year. The impact of sampling variability is partially mitigated by smoothing, or averaging, data across 3-year periods.

Links:

[1] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/2014-report/xl0/economic-cost-icd-9-cm-codes

[2] https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/

[3] https://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml

[4] http://www.bea.gov/national/index.htm#gdp

[5] https://www.bea.gov/national/

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.1.pdf

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.1.csv

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8b01png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.B.0.1.png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.1.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.1.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8b11png

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.B.1.1.png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8b21png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.B.2.1.png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.2.pdf

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.2.csv

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.3.pdf

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.3.csv

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.4.pdf

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.4.csv

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.5.pdf

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.5.csv

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.2.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.2.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.3.pdf

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.3.csv

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.4.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.4.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.5.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.5.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.6.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.1.6.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.1.pdf

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.1.csv

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8c11png

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.C.1.1.png

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.2.pdf

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_TA8.2.csv

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8c21png

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.C.2.1.png

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.2.pdf

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.2.csv

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.3.pdf

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.3.csv

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.4.pdf

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.4.csv

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.5.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.5.csv

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.6.pdf

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.2.6.csv

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.3.pdf

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.3.csv

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.1.pdf

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.1.csv

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.1.pdf

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.1.csv

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d11png

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.1.1.png

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.1.pdf

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.1.csv

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d12png

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.1.2.png

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.2.pdf

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.2.csv

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.3.pdf

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.3.csv

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.4.pdf

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.4.csv

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.5.pdf

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.5.csv

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.6.pdf

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.4.6.csv

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.7.pdf

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.7.csv

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d13png

[77] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.1.3.png

[78] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.2.pdf

[79] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.2.csv

[80] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.3.pdf

[81] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.3.csv

[82] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.4.pdf

[83] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.4.csv

[84] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.5.pdf

[85] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.5.csv

[86] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.6.pdf

[87] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.5.6.csv

[88] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.8.pdf

[89] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.8.csv

[90] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d15png

[91] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.1.5_0.png

[92] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.9.pdf

[93] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.9.csv

[94] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d14png

[95] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.1.4.png

[96] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.14.pdf

[97] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.14.csv

[98] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d21png

[99] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.2.1.png

[100] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.2.pdf

[101] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.2.csv

[102] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.3.pdf

[103] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.3.csv

[104] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.4.pdf

[105] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.4.csv

[106] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.5.pdf

[107] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.5.csv

[108] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.6.pdf

[109] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.6.csv

[110] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d22png

[111] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.2.2.png

[112] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d23png

[113] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.2.3.png

[114] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/viiid1/person-expenditures

[115] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8d24png

[116] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.D.2.4.png

[117] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8e01png

[118] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.E.0.1.png

[119] http://www.bea.gov/national/xls/gdplev.xls

[120] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8f01png

[121] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.F.0.1.png

[122] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.12.pdf

[123] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.12.csv

[124] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8f02png

[125] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.F.0.2.png

[126] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.13.pdf

[127] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.13.csv

[128] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8g01png

[129] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.G.0.1.png

[130] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.19.pdf

[131] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.19.csv

[132] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.20.pdf

[133] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.20.csv

[134] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.21.pdf

[135] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.21.csv

[136] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8g02png

[137] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.G.0.2.png

[138] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib23/connective-tissue-disorders

[139] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib30/gout

[140] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib21/rheumatoid-arthritis

[141] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiib10/osteoarthritis

[142] https://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/iiaf0/economic-burden

[143] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8h01png

[144] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.H.0.1.png

[145] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8h02png

[146] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.H.0.2.png

[147] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.16.pdf

[148] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.16.csv

[149] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.17.pdf

[150] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.17.csv

[151] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.18.pdf

[152] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.18.csv

[153] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g8i01png

[154] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G8.I.0.1.png

[155] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_VIII%20econ%20tables%20summary_by%20file.pdf

[156] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_VIII%20econ%20tables%20summary_by%20content.pdf

[157] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/2016-econ-tables-filepng

[158] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/2016%20econ%20tables%20by%20file.png

[159] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/2016-econ-tables-contentpng

[160] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/2016%20econ%20tables%20by%20content.png