[15]

[15]

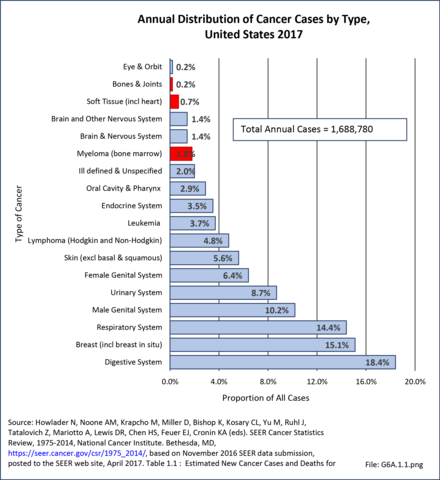

Musculoskeletal neoplasms cause significant morbidity and mortality, although less commonly than lung, breast, kidney, and certain other cancers. This significant burden is especially true in young patients who are more likely to develop cancers such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Musculoskeletal neoplasms and sarcomas usually require concerted treatment efforts by coordinated medical teams. These teams are typically led by a subspecialty of physicians known as orthopedic oncologists. Because of the relative infrequency of musculoskeletal sarcomas, few institutions gather sufficient numbers to provide thorough epidemiologic and descriptive data. Therefore, tumor registry data are necessary to gather enough cases to generate meaningful data.

The following discussion is based on concerted analysis that incorporates the two largest tumor registries in the United States, the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) of the American College of Surgeons [1] (ACS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer lnstitute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results [2] (SEER) program. Actual incidence, death rates, and survival statistics are difficult to determine. The two databases derive slightly different numbers, and the numbers change annually with newly reported data. Thus, a direct comparison of NCDB and SEER is not possible. Sources for data cited in tables and graphs are shown. Sources available at the time of analysis may no longer be available.

The NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The data used in this study and this report are derived from analysis of a cohort of patients registered and treated 2004-2015 and the resulting de-identified NCDB file comprising more than 1,500 Commission-accredited cancer programs. Data are collected from all institutions wishing to be accredited by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Each accredited institution is required to report all patients with cancer treated at their institution, including annual follow-up data. Site visits and interaction between American College of Surgeons cancer database personnel and the local reporting institutions verifies a minimum of 90% case capture and reporting for each institution. Multiple internal checks verify the data accuracy. It is estimated that the approximately 1,500 reporting institutions each year treat approximately 72% of all patients with malignancies in the United States.1 The primary author was granted research access to the database under the Participant User File (PUF) research program. In his prior PUF-based research (including prior data reported in the predecessor of this publication), the accessible data was only for cases in patients 18 years old and older, thus creating age-associated limitations of the NCDB dataset. The most recent database reported herein, however, includes patients of all ages treated 2004-2015, inclusive. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator and authors of this chapter. Data from the NCDB was used in the analysis for certain demographic, treatment and survivorship analyses for musculoskeletal cancers.

The SEER database is the main program used by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to support cancer surveillance activities. It is the most comprehensive and authoritative source of information on cancer incidence, prevalence, mortality, survival, and lifetime risk in the United States. The SEER Program currently collects and publishes cancer incidence and survival data from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 34% of the U.S. population.2 Data is available from 1974 to 2016 and includes more than 10 million cases.

We also derived some tumor incidence estimates by analysis and extrapolation from one of the author's case series data compiled from his practice experience. Dr. William Ward was the only orthopedic oncologist at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center in Winston Salem, NC, during the period between 1991 and 2005. Virtually all cases of osteosarcoma in North Carolina were treated by one of the very few orthopedic oncologists in North Carolina during that time. Dr. Ward's personal surgical database contains detailed incidence data regarding many musculoskeletal neoplasms. Comparing the incidence of osteosarcomas in the United States with that treated by Dr. Ward, we were able to extrapolate, using similar proportional estimates, to the national incidence of tumors for which there were no national registry data. Typically, aggressive benign bone and benign soft tissue tumors are most likely to be treated by orthopedic oncologists rather than by non-oncological-trained surgeons. However, because there is no way to estimate the numbers of patients treated by orthopedic surgeons and other surgeons not specifically trained in orthopaedic oncology, the derived national data estimates will be conservative because of the methodology used. All estimates in this chapter derived from the above methodology will be clearly identified as an extrapolation via this incidence estimation.

All tissues are made up of individual cells. Tumors, also known as neoplasms, are formed by uncontrolled and progressive excessive abnormal growth and multiplication of cells. In malignant tumors, the tumor cells continue to multiply and divide beyond the initial site. If unchecked, malignant tumors can cause death as they spread, or metastasize, to vital areas of the body. Benign tumors, on the other hand, remain localized and do not spread or metastasize to other body locations. They rarely threaten the life of the patient although they can cause significant injury or morbidity at the site of the tumor.

Muscle, bone, nerves, blood vessels, fat, and fibrous tissues are all connective tissues and are the tissue types that comprise musculoskeletal tissues and structures; therefore, tumors of these tissues form the basis of this report. Malignant tumors of the bone and connective tissue are also known as sarcomas, whereas cancers in most other organs are generally referred to as carcinomas.

Primary tumors are tumors of any organ or tissue that are composed of cells derived from that organ or tissue itself. Secondary, or metastatic tumors, are tumors in any organ or tissue that originated in a distant organ or tissue. Therefore, primary bone and soft tissue tumors originate in bone or connective tissue itself. Secondary or metastatic bone or connective tissue tumors began elsewhere and spread (metastasize) to the bone or connective tissues, retaining the cellular composition of the original tumor site. Primary tumors can be benign, which means they do not spread through the body to other sites, or malignant (cancerous), meaning they can and do spread to other places in the body.

Most musculoskeletal cancers, or sarcomas, are named by the Latin root word for the type of malignant tissue they produce. Thus, osteosarcomas are composed of malignant bone (osteo) producing cells; chondrosarcomas are composed of malignant cartilage (chondro) producing cells; liposarcomas are composed of malignant fat producing (lipo) cells; rhabdomyosarcomas create malignant muscle tissue (rhabdomyo); fibrosarcomas produce malignant connective tissue (fibro), and so on.

Secondary bone tumors that spread to the bone from malignancies in other organs such as lung, breast, and prostate cancers (metastatic cancers) are far more numerous than primary bone cancers. Although metastatic cancers to bone cause extensive morbidity from pain and fractures caused by bone weakening, such cancers are not the primary focus of this chapter. However, a section on secondary bone and joint cancers [3] details some of the effects of this condition and its associated morbidity.

Hematologic (bone marrow) tumors are often not included in treatises on “bone cancer.” The three most common are leukemia (rarely weakens bone or causes fractures), lymphoma (can destroy bone structure and weaken bone causing fractures), and myeloma (often causes bone destruction). The latter two often cause bone weakness, pain, and fractures, so these two bone marrow tumors are included in most studies on bone cancers. Leukemias are rarely included since they only rarely cause significant bone weakness or fractures, therefore we have left them out of this chapter as well.

The incidence of cancer is defined as the number of new cancers of bone and connective tissue in a specific population during a year. The incidence rate is expressed as the number of cancers per 100,000 population at risk. In general, it does not include recurrences. Because of the low number of new cases, the incidence rate in this report is expressed as the number per one million population at risk.

Prevalence is defined as the number of people alive on a certain date in a population who have the disease and have previously had a diagnosis of the disease. It includes new (incidence) cases and pre- existing cases and is a function of past incidence and survival.

A cancer mortality rate is the number of deaths, with cancer as the underlying cause of death, occurring in a specific population during a year. It is calculated the same as the incidence rate.

Cancer survival statistics are typically expressed as the proportion of patients alive at some point subsequent to the diagnosis of their cancer. Observed all-cause survival is an estimate of the probability of surviving all causes of death. Net cancer-specific survival (policy-based statistic) is the probability of surviving cancer in the absence of other causes of death. It is a measure that is not influenced by changes in mortality from other causes and, therefore, provides a useful measure for tracking survival across time, and comparisons between racial/ethnic groups or between registries. Crude probability of death (patient prognosis measure) is the probability of dying of cancer in the presence of other causes of death. It is a better measure to assess the impact of cancer diagnosis at an individual level since mortality from other causes play a key role. It measures mortality patterns experienced in a cohort of cancer patients on which many possible causes of death are acting simultaneously. The crude measure is reported as a cumulative probability of death from cancer rather than survival.3

Net cancer-specific survival measures are relative survival and cause-specific survival. Relative survival is the ratio of the proportion of observed survivors (all causes of death) in a cohort of cancer patients to the proportion of expected survivors in a comparable cohort of cancer-free individuals. The formulation is based on the assumption of independent competing causes of death. Cause-specific survival is a net survival measure representing survival of a specified cause of death in the absence of other causes of death. Estimates are calculated by specifying the cause of death. Individuals who die of causes other than those specified are considered to be censored.4

Bone and connective tissue neoplasms, which include bone and joint sarcomas, myelomas, and soft tissue sarcomas, are uncommon when compared with other cancers and with other musculoskeletal conditions, accounting for about 2.4% of annual cancer cases between 2010 and 2014 (approximately 50,000 cases). This share is higher than the 2.2% reported for 2006 to 2010, and the 1.9% for 2002 to 2006. Estimated cases for 2017 were slightly lower, at 46,000 cases, but represented 2.7% of all new cancer cases. The annual average number of new bone and joints cancer cases, excluding myeloma and soft tissue, reported between 2010 and 2014 was 4,126 cases, with an average of 1,440 deaths from bone and joints cancer each year. Estimates for 2017 are 3,260 new cases and 1,550 deaths. Data cited is from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute and is used to illustrate the burden of bone and connective tissue neoplasms. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.0 PDF [8] CSV [9], Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11]; and Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13])

The three most common primary cancers of bones and joints are osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma. Together they account for more than 80% of true primary bone and joint cancers. The ages at which these cancers most often occur vary. Osteosarcoma, a malignant bone tissue tumor commonly found near the growing end of the long bones, is the most common, and occurs most frequently in teens and young adults. Ewing sarcoma, a tumor often located in the shaft of long bones and in the pelvic bones, occurs most frequently in children and youth. Chondrosarcoma, a sarcoma of malignant cartilage cells, often occurs as the result of malignant degeneration of pre-existing cartilage cells within bone, including enchondromas (a benign tumor), and is primarily found among middle age and older adults. However, the majority of enchondromas never undergo malignant change; therefore, the routine resection of benign enchondromas is unwarranted. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [16] CSV [17], Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [18] CSV [19], Table 6A.B.1.3 PDF [20] CSV [21], and Table 6A.B.1.4 PDF [22] CSV [23])

Of the three, chondrosarcoma has the best prognosis, while Ewing sarcoma is generally considered to have the worst prognosis, followed closely by osteosarcoma. However, this perception is largely due to the greater tendency for osteosarcomas to present as high-grade tumors and for chondrosarcomas to present as low-grade tumors. When analyzed by stage, a recent survivorship analysis of a prior cohort of patients in the NCDB PUF database revealed similar survivorship rates for low-grade chondrosarcoma compared to low-grade osteosarcoma, and similar survivorship rates for Ewing sarcoma and high-grade osteosarcoma. By definition, all cases of Ewing sarcoma are high-grade, the most aggressive category of cancer, with full potential to metastasize and bring about death. High-grade chondrosarcoma has a worse prognosis when compared to high grade osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma.1

In the current NCDB analysis, only 4% of osteosarcomas are of Grade 1, the lowest grade, whereas 48% of chondrosarcoma are Grade 1. Therefore, chondrosarcomas have a higher proportion of low-grade cases than the other two bone and joint cancers, which accounts for its overall higher survival rate and the perception that it is not be as lethal. Conversely, 2% of all chondrosarcomas with histologic grading were reported as Grade 4, whereas 40% of osteosarcomas were reported as being in the most aggressive Grade 4 category. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.8 PDF [26] CSV [27])

A fourth type of cancer is myeloma, a malignant primary tumor of the bone marrow formed from a type of bone marrow cells called plasma cells (the cells that manufacture antibodies). Although not classified as a bones and joint cancer, it typically causes extensive changes or damage to the bone structure itself, causing fractures, pain, and hypercalcemia (a condition in which the calcium level in blood is above normal, which can weaken bones, create kidney stones, and interfere with how the heart and brain work). Because of the associated bone destruction, myeloma is generally included in analysis of bone cancers. Myeloma usually involves multiple bones simultaneously. The isolated single-bone version of myeloma is called plasmacytoma, but virtually all cases of isolated plasmacytoma evolve into full-fledged multiple myeloma within 5 to 10 years after diagnosis of the plasmacytoma. Like leukemia and lymphoma, myeloma is more properly considered a primary cancer of the hematopoietic bone marrow (stem cells that give rise to other blood cells.). However, leukemia and lymphomas generally are not considered primary bone cancers, presumably because of the lower likelihood of structural bone destruction and associated complications. NonHodgkin's lymphomas, however, as well as myelomas, warrant some consideration in a report on the burden of musculoskeletal diseases due to the frequency of bone destruction and pathological fractures requiring operative intervention.

The reader is referred to the data tables 6A.B.1.1 thru 6A.B.1.9 for a more robust appreciation of these tumors. These tables show the latest NCDB demographic and survivorship analyses of bone and joint cancers, providing additional understanding of the demographics, age distribution, anatomic distribution, nature, treatment and prognosis of these sarcomas and their treatments and results.

Adamantinoma: A rare bone cancer, making up less than 1% of all bone cancers. It almost always occurs in the bones of the lower leg and involves both epithelial and osteofibrous tissue. It generally has a favorable prognosis.

Angiosarcoma: A cancer that forms from cells that are in the lining of blood vessels and lymph vessels. It often affects the skin and may appear as a bruise-like lesion that grows over time. The disease most commonly occurs in the skin, breast, liver, spleen, and deep tissue. It typically has an aggressive course and a poor prognosis.

Chondroblastoma – malignant: Chondroblastoma is a rare, usually benign, tumor of cartilaginous origin. It typically arises in the epiphysis of a long bone. Malignant chondroblastomas, which may occur many years after the original lesion, are extremely rare. Our analysis of the NCDB database reveals a usually good prognosis, with 95% survivorship at 5 years. Establishing the diagnosis in such rare and unusual cases is challenging at best. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF CSV)

Chondrosarcoma: A bone cancer that develops from cartilage cells. Cartilage is the specialized, gristly connective tissue that is on the ends of bones with articulating joints that cushion the bone ends and allow motion over its smooth lubricated surfaces. Primitive cartilage is present in adults and the tissue from which most bones develop. Chondrosarcoma develops primarily in the pelvis, scapulae, chest bones, long bones, and spine.

Chordoma: A rare type of slow growing cancerous tumor that can occur anywhere along the spine, from the base of the skull to the tailbone. It derives from the notochord, an embryonic tissue generally considered to be the precursor to intervertebral disc tissue.

Ewing sarcoma: A cancerous tumor that grows in the bones or in the tissue around bones (soft tissue)—often the legs, pelvis, ribs, arms, or spine. Ewing sarcoma can spread to the lungs, bones, and bone marrow.

Fibrosarcoma: A malignant tumor consisting of fibroblasts (connective tissue cells that produce the collagen found in scar tissue) that may occur as a mass in the soft tissues or may be found in bone.

Giant cell tumor of bone - malignant: A relatively uncommon tumor of bone characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells (osteoclast-like cells). Malignancy in giant-cell tumor is uncommon and occurs in about 2% of all cases. However, if malignant degeneration does occur, it is likely to metastasize to the lungs. It often arises in sites of previously treated benign giant cell tumors that were treated with radiation therapy.

Hemangioendothelioma: A rare type of vascular tumor that affects the epithelial cells which line the inside of blood vessels. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma tumors most commonly affect the soft tissues, liver, lungs, and bones.

Leiomyosarcoma: A type of soft tissue sarcoma that develops in muscle, fat, blood vessels, or any of the other tissues that support, surround, and protect the organs of the body. Leiomyosarcoma is one of the more common types of soft tissue sarcoma to develop in adults.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: Most often more recently classified as pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) also can be listed as plasmosphic sarcoma not otherwise specified (PS-NOS). It also was often formerly known as a type of fibrosarcoma. It is historically considered the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma. It has an aggressive biological behavior and a poor prognosis, and primarily affects the extremities.

Neoplasm - malignant: The term "malignant neoplasm" means that a tumor is cancerous. When diagnosed it may mean further testing is needed to identify the specific type of cancer or sarcoma.

Osteosarcoma: The most common type of cancer that starts in the bones. The cancer cells in these tumors look like early forms of bone cells that normally help make new bone tissue, but the bone tissue in an osteosarcoma is not as strong as that of normal bones. Therefore, affected bones are subject to pathologic fracture (fractures caused by bone weakened due to underlying disease). Without proper treatment, osteosarcome is fatal.

Primitive peripheral neuroectodermal tumor: Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are a group of highly malignant tumors composed of small round cells of neuroectodermal origin that affect soft tissue and bone. PNETs exhibit great diversity in their clinical manifestations and pathologic similarities with other small round cell tumors. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors (pPNETs) are tumors derived from tissues outside the central and autonomic nervous system.

Sarcoma (NOS): A usually aggressive malignant mesenchymal cell tumor most commonly arising from muscle, fat, fibrous tissue, bone, cartilage, and/or blood vessels that is not otherwise specified (NOS).

SEER estimates an average of 3,260 people were newly diagnosed with cancer of the bones and joints, excluding myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemias, in 2017. During the same year, an estimated 1,550 people died from cancer of the bone and joints. The number of new cases of bone and joint cancers was estimated to be 1.0 per 100,000 people per year during the years 2012-2016.1 However, death rates from bone and joint cancers have declined slightly (0.2% per year) since 1982-2016, following a 9.9% decline from 1975-1982.2 Approximately 40% of bone cancers are diagnosed at a localized stage, for which the 5-year relative survival is 85%.3 The overall 5-year relative survival rate in the 2004-2015 NCDB Database set for Bone and Joint cancers was 65% but is higher for all combined chondrosarcomas (74%) than all combined osteosarcomas (60%). (Reference Table 6A.A.1.0 PDF [8] CSV [9] and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31]. See Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [16] CSV [17] and Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [18] CSV [19] for the NCDB database data regarding the two- and five-year survivorship of all bone and joint sarcomas.)

Myeloma occurs up to ten times more frequently than bone and joint cancers and is not defined as a rare cancer as the incidence is just over the 6/100,000 rare cancer definition. In 2019, myeloma was estimated to be diagnosed in 32,110 persons per year, an incidence rate of 6.9 per 100,000 persons per year. An estimated 12,960 persons will die of myeloma in 20194, with a death rate of 3.3 per 100,000 persons. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [34] CSV [35] and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [36] CSV [37])

Most bone cancers and soft tissue sarcomas are found more frequently in males than females and more frequently among whites than those of any other race, although there are exceptions or outliers to these generalizations for certain subtypes of bone and soft tissue tumors. However, reported rates have varied slightly for both genders and by race for the past decade. The average annual incidence of bone and joint cancers between 2012 and 2016 was 1 in 100,000, a slightly higher rate than reported in the first decade of the 21st century. The rate among white males was 1.2 in 100,000, while, among white females it was 0.9 in 100,000. The lowest reported rate, 0.6/100,000 was found for females of the Asian or Pacific Islander race. The incidence of cancer of the bones and joints in the United States is comparable to several site-specific oral cancers (i.e., lip, salivary gland, floor of the mouth), cancers of the bile duct, cancers of the eye, and Kaposi's sarcoma, which affects the skin and mucous membranes and is often associated with immunodeficient individuals with AIDS. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.1 PDF [42] CSV [43] and Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11])

As with bone and joint cancers, males have a higher incidence of myeloma than do females, with an average of 8.1 cases in 100,000 white males to 4.9 cases in 100,000 white females for the years 2012-2016. Blacks have a much higher incidence rate of myeloma than whites, with 16.3 cases in 100,000 black males to 11.9 cases in 100,000 black females for the years 2012-2016 while American Indians/Alaska Natives and Asian/pacific islanders have lower incidence rates. The incidence of myeloma in the United States is comparable to the incidence of esophageal, liver, cervical, ovarian, brain, and lymphocytic leukemia cancers. Death rates reflect incidence. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [34] CSV [35] and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [36] CSV [37])

The gender make-up of bone and joint cancers from the most recent NCDB (2004-2015) cohort also shows a male predominance for most of the bone and joint cancers and cancer subtypes, with parosteal osteosarcoma showing the major break from this generalization with 34% male and 66% female patients with this cancer. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.6 PDF [48] CSV [49] and Table 6A.B.1.7 PDF [50] CSV [51])

The median age for cancers of the bones and joints has risen slightly, to age 43 years, in recent years. However, it remains the leading cause of cancer in young persons under the age of 20 years. More than one in four (26%) diagnoses of bone and joints cancer is in children and youth under the age of 20 years, with 42% of cases diagnosed in persons younger than 35 years. Death from bone and joints cancer also affects children and youth at a high rate, with 12% of deaths occurring in those under 20 years of age and one fourth (27%) in those younger than 35 years. Males are typically diagnosed with bone cancers, and die from bone cancer, at an age several years younger than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11]; Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [54] CSV [55]).

Younger patients have a higher likelihood of surviving bone cancers. For example, the 5-year survivorship for classic osteosarcoma is 67% in 10 to 20-year-old patients, compared to 34% in patients in their 60s, 19% for patients in their 70s, and only 7% in patients in their 80s and older. Similar declining survivorship is noted with increasing age for Ewing Sarcoma and chondrosarcoma (unpublished NCDB current data analysis).

Myeloma, on the other hand, is primarily a cancer found among elderly persons, with a median age of 69 at the time of diagnosis and 75 at time of death from myeloma. Sixty-two percent (62%) of new myeloma cases are diagnosed in persons age 65 years and older, with more than three in four (78%) of deaths due to myeloma occurring in those 65 and older. Again, males are typically diagnosed with myeloma at ages a few years younger than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11]; Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [54] CSV [55])

The incidence of bone and joints cancers is higher among non-Hispanic whites than found in other race/ethnicity groups, while myeloma is higher in non-Hispanic blacks. Death rates follow the same race/ethnic lines. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.1 PDF [42] CSV [43]; Table 6A.A.1.1.2 PDF [58] CSV [59]; Table 6A.A.1.2.1 PDF [34] CSV [35]; and Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [36] CSV [37])

Causes of health disparities are complex and can include interrelated social, economic, cultural, environmental, and health system factors, and may arise, at least in part, from inequities in work, wealth, education, housing, and overall standard of living, as well as social barriers to high-quality cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment services.1

Annual population-based mortality rates due to cancers of bones and joints are low, averaging four deaths per one million people since the early 1990s.1 While the mortality rate from bone and joint cancer dropped by approximately 50% from that of the late 1970s, no significant improvement in this rate has been observed over the past 20 years.2 Males have a higher mortality rate than females for all race/ethnic groups. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.2 PDF [58] CSV [59])

Because bone and joint cancers affect younger populations more than other types of cancers, the median age at death, 61 years of age, is younger than any other type of cancer. There is a higher death rate in older individuals, but a higher incidence rate in younger individuals. At 0.1% risk, bone and joints cancer also has one of lowest life-time risks. This compares to 12% risk for breast and prostate cancer, the two highest risk cancers. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31] and Table 6A.A.1.6.1 PDF [60] CSV [61]; and Table 6A.A.1.6.2 PDF [62] CSV [63])

The overall 5-year survival rate in 2009-2015 for bone and joint cancers was 66.2%, placing it roughly in the middle of all cancers for 5-year survival and comparable to several more common cancers such as rectal, cervical, and soft tissue cancers.3 This is a survival rate increase of 27% since 1975, when the 5-year survival rate was 52%. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.2 PDF [64] CSV [65])

By extrapolation from median age at diagnosis and median age at death, one could estimate a median survival rate. However, this extrapolated survival time is misleading and inaccurate as younger patients, who typically are healthier and can tolerate more aggressive treatments, have improved survival compared to older individuals, who cannot tolerate such aggressive treatments and have poorer survival, greatly affecting this derived or extrapolated estimate of survivorship.

The overall 5-year survival rate for the primary types of bone and joint cancers varies by type and subtype of cancer, how it responds to treatment, and the degree to which the cancer has spread. Osteosarcoma diagnosed and treated before it has spread has a reported general survival rate between 60% and 80%; if it has already spread at the time of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate is reported to be between 15% and 30%.4

If Ewing sarcoma is found before it metastasizes, the 5-year survival rate for children and youth is about 70%, with a survival rate of 78% reported for children under age 5, dropping to around 60% survival for adolescents age 15 to 19. However, if already metastasized when found, the 5-year survival rate drops to 15% to 30%.5

The annual population-based mortality rate of myeloma has been an average of 33 persons per one million population between 2001 and 2016. The mortality rate from myeloma has remained relatively constant since the mid-1970s. The 5-year survival rate for myeloma, 50%, is one of the lowest for all cancers; however, due to being primarily a cancer of older persons, this age-relatedness may, in part, reflect survival regardless of the presence or absence of myeloma. The median calculated rate of survival after diagnosis of myeloma is only 6 years. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.2.2 PDF [36] CSV [37] and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31])

Within the NCDB, no change in the overall survival rates for patients diagnosed and treated in the years 1985 to 1988 compared to patients between 1994 and 1998 was found. There have been no substantial changes in therapies utilized for osteosarcoma since 1998, and the overall 1998-2010 NCDB data reveals no significant improvement, with an approximate 50% 5-year overall survival. However, the survival rate varies greatly with the histologic subtype of sarcoma. For instance, the 5-year relative survival rate is 56% for classic high-grade osteosarcoma, 89% for parosteal osteosarcoma, and 37% for osteosarcoma associated with Paget's disease of the bone. The most recent NCDB database investigation the three primary authors have performed, which covered patients diagnosed between 2004-2015, inclusive, is summarized in the data tables attached to this chapter. These data provide the analysis of the numbers of cases reported during these years, along with the Kaplan-Meier survivorship of the major diagnostic groupings, as well as of the subgroups and age-based for the various primary bone and joint tumors reported and treated 2004-2015. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.1 PDF [16] CSV [17]; Table 6A.B.1.2 PDF [18] CSV [19]; Table 6A.B.1.3 PDF [20] CSV [21]; and Table 6A.B.1.4 PDF [22] CSV [23])

The above and all other reported survivorships in this chapter were generated using SAS/STAT software, Version14.2 for Windows 3. Copyright 2002-2012, SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. As stated previously, the NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The data used in this study and this report are derived from a de-identified NCDB file comprising more than 1,500 Commission-accredited cancer programs. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator and authors of this chapter.

The economic burden of bone cancers can be great. The more advanced the disease, the worse the prognosis and, accordingly, the more expensive the treatments. It is likely that early detection, and, certainly, prevention if possible, could drastically reduce costs. Several expensive treatments are required to address these tumors. In the 2007 report by Damron, Ward, and Stewart,1 it was noted that the most frequent initial treatments varied widely based on the type of sarcoma and, although not reported, also on the stage of the disease as well.

Collectively, they reported surgery alone was the most common initial treatment for chondrosarcomas (69%), whereas Ewing sarcoma treatments were divided between surgery and chemotherapy (24% of cases), radiation and chemotherapy (23%), and chemotherapy alone (18%). With osteosarcoma, when initial treatment was known, the largest group received surgery and chemotherapy (46%). Surgery was reported as part of the initial treatment in 71% of osteosarcoma patients, 83% of chondrosarcoma patients, and 47% of Ewing sarcoma patients. The most frequent operations performed were limb-sparing radical resections and excisions. When the type of surgery was defined and known, limb-preservation surgery was performed in 69% of osteosarcomas, 79% of chondrosarcomas, and 81% of Ewing sarcomas.1

The frequencies of the various treatment modalities employed in the latest reported (2004-2015) NCDB cohort are shown in the data tables attached to this section for bone and joint cancers and soft tissue cancers. As shown in the table, for Osteosarcoma NOS 76% had surgery, 74% had chemotherapy, and only 8% had radiation. For Ewing Sarcoma, the numbers were 51%, 85%, and 45%, respectively. For Chondrosarcoma NOS, the numbers were 85%, 3%, and 10%. These distributions reflect the widely different treatments of these three major categories of bone and joint cancers. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.9 PDF [74] CSV [75] and Table 6A.B.2.6 PDF [76] CSV [77])

In Dr. Ward's personal series of more than 100 osteosarcomas, amputation has been required in only 17% of patients, but almost all remaining patients have had surgical resection, limb reconstruction, and chemotherapy.1 The authors believe Dr Ward’s series is a reasonable approximation of treatments employed by most orthopedic oncologists in the US today.

Multiple therapies may be needed throughout the course of the patient's disease, especially in more advanced cases. In later stages of the disease for those not cured with surgery alone, significant costs will accumulate as patients develop pulmonary disease and ultimately die. Hormone therapy, immunotherapy, bone marrow transplant, and endocrine treatments each accounted for 1% or less of initial treatments. However, in severely affected individuals in whom standard treatments fail, these alternative treatments may be tried more frequently. Currently, the authors are not aware of any data source that reports the rate of utilization of such late treatments.

All these treatments are costly to administer. Per-patient cost will vary widely depending on the treatments utilized, and the number and intensity of treatments. Overall, treatment for bone and joint cancers can easily exceed $100,000 for a single patient. This is particularly true if a patient receives surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. If one includes bone-replacing endoprostheses or artificial limbs used in cases requiring amputation, the cost will be much higher. In addition to the direct medical cost, there are extensive indirect and social costs from lost work time and disability. For some patients, healthcare costs associated with their bone and joint cancers will be ongoing.

Analysis of the most recent NCDB insurance data, which covers all ages and covers the years 2004-2015 inclusive, available for 18,881 reported bone and joint cancer cases show Medicare and Medicaid covering 16.76% and 14.71%, respectively, with private insurance covering 57.33%, other government payors covering 1.9% with 5.05% uninsured and 4.24% with unknown insurance status. (Reference Table 6A.B.1.11 PDF [80] CSV [81])

Almost all cancers have preferential sites to which they spread or metastasize, resulting in secondary cancers. Secondary bone cancer is much more common than primary bone cancer and results in great morbidity and pain. The three most common sites to which cancers metastasize are lung, liver, and bone. The skeleton is the most common organ affected by metastatic cancer, and the site of disease that produces the greatest morbidity. The most commonly encountered cancers that readily and frequently spread to bone are cancers of the breast, lung, kidney, prostate, gastrointestinal tract, and thyroid gland. The incidence of bone metastases in lung cancer patients is approximately 30% to 40%, with the median survival time (MST) of patients with such metastases 6 to 7 months.1 At postmortem examination, 70% of patients dying of breast and prostate cancer have evidence of metastatic bone disease. Cancers of the thyroid, kidney, and bronchus also commonly give rise to bone metastases, with an incidence at postmortem examination of 30% to 40%.2 Brain and ovarian cancers rarely spread to bone. Many other cancers have intermediate rates of spread to bones.

A tumor formed by metastatic cancer cells is called a metastatic tumor or a metastasis. The cancer cells in their new metastatic site closely resemble the original or primary cancer from which the cancer initially arose. For example, breast cancer that spreads to the bone and forms a metastatic tumor is still considered metastatic breast cancer, not true bone cancer. The cancerous tissues in the bone will still exhibit the microscopic appearance of breast tissue and breast cancer when it is inspected or viewed under a microscope. Many lay people will now refer to it as bone cancer, but to the physician, bone cancer implies a cancer that started or originated in the bone, such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, or myeloma, as discussed previously.

Metastatic bone disease complications are termed skeletal related events (SREs). SREs include pain, pathologic fracture, vertebral deformity and collapse, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia (overabundance of calcium in the blood) of malignancy. These complications result in impaired mobility and reduced quality of life (QOL) and have a significant negative impact on survival.2 In addition, metastatic disease may remain confined to the skeleton, with the decline in quality of life and eventual death almost entirely due to skeletal complications and their treatment.

The prognosis of metastatic bone disease is dependent on the primary site, with breast and prostate cancers associated with a survival measured in years compared with lung cancer, where the average survival is only a matter of months. Survival rates for secondary bone cancer depend on patient factors such as age, overall health, treatment, and response to treatment. However, due to the advanced stage of cancer that has spread to the bone, survival rates are much lower than for primary cancer without such spread.

The fundamental treatment for disease control for bone metastasis from advanced cancer is systemic chemotherapy and radiation of the bone lesions. Prevention and treatment of bone metastases is highly dependent on an effective treatment being employed against the primary cancer. As a direct treatment for bone metastases themselves, radiation therapy, surgery, and bisphosphonates are the mainstays of treatment. Intravenous bisphosphonate, such as zoledronic acid, have been shown to prevent or reduce pathologic fractures and may reduce these costs.3 With the 1995 FDA approval of the use of bisphosphonate medications to prevent such fractures, the incidence of fractures in treated patients with bone metastasis has significantly decreased. Fracture rates reported in cases of metastatic disease and myeloma have been demonstrated in multiple studies to be diminished by roughly 50%. The bisphosphonate medications work by interrupting a biochemical pathway required for bone breakdown by osteoclasts, the cells that normally remove bone in the process of bone remodeling. This bone breakdown step is overactivated in the presence of bony metastases, causing bone loss, bone destruction, and ultimately fractures from the weakening of the bone. Thus, the introduction of bisphosphonate medication has been a major advance during the past 20 years, with significant impact on the health of those with myeloma and metastatic cancer to the bone. Most pathologic fractures encountered currently are in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic cancer who have not received prophylactic treatments because the cancer had not been diagnosed.

Dr. Ward has had several anecdotal cases in the last year (2018-2019) with metastatic lung and other cancers that have metastasized to bone in whom the cancer elsewhere in the body is responding favorably to newer targeted chemotherapy and immunotherapy regimens, but the bone metastasis for some reason is not responding favorably, requiring more extensive surgical treatment of the unresponsive bone metastatic lesion. Whether or not this will become a more common challenge in the future is anyone’s guess, but with several cases seen by one physician in a short time, it raises the possibility that more extensive bone resection treatments may become more necessary for metastatic bone lesions as these individualized systemic targeted treatments are employed in greater numbers and are capable of controlling the disease in the rest of the body.

The economic burden of SREs in patients with bone metastases is substantial. Several recent studies show that the estimated lifetime SRE-related cost per patient suffering from bone metastatic disease (BMD) resulted in medical costs more than twice the treatment cost for cancer in patients without BMD.1,2 Finding cures and effective treatments for all types of cancer can help reduce the prevalence and costs associated with bone and joint cancer.

Overall, cancers metastatic to bone cause significant pain and morbidity. Approximately 50% of patients with metastatic cancer of lung, breast, prostate, and kidney develop bony metastases prior to death. Untreated, these metastases can lead to pathological fractures and cause great pain and disability. Thus, the elucidation of the biochemical steps involved in bone destruction and the development of drugs to combat such steps, have been an example of tremendous scientific advancement and achievement in the field of cancer research and treatment.

Soft tissue tumors, like bone tumors, are called sarcomas, and are encountered more frequently than bone and joints tumors. Soft tissue tumors originate in connective or non-glandular tissue and can develop in any part of the body that contains fat, muscle, nerve, blood vessels, fibrous tissues, and in any deep tissues, including tissues surrounding joints, bones, or deep subcutaneous tissues. More than half of soft tissue sarcomas develop in the arms or legs. About one in five (20%) are found in the abdominal cavity and present with symptoms similar to other abdominal-based health problems. The rest begin in the head and neck area or in and on the chest or abdomen (about 10% each).1 The differentiating feature of soft tissue tumors (sarcomas) is that they arise from the connective tissues rather than from gland forming organs such as kidneys, lungs, intestines, breasts, prostate, or thyroid glands.

There also are a vast number of non-malignant soft tissue neoplasms and tumors such as lipomas. In addition, typically included are cystic lesions of the deep tissues. Additional information on soft tissue sarcomas can be found in multiple sources such as Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors.2

The reader is referred to the data tables 6A.B.2.1 thru 6A.B.2.7 for a more robust appreciation of these tumors. These tables show the latest NCDB demographic and survivorship analyses of soft tissue cancers, providing additional understanding of the demographics, anatomic distribution, nature, treatment and prognosis of these sarcomas and their treatments and results.

There are multiple soft tissue sarcomas with varying degrees of aggressive behavior, but virtually all have the capacity to metastasize and cause death. Treatment for high-grade soft tissue sarcomas is typically resection (removal) and radiation. Chemotherapy is playing an ever-increasing role, especially in high-grade (fast-growing) and metastatic cases.

Cancer cells are often referred to as differentiated versus undifferentiated. Differentiation describes how much or how little the tumor tissue microscopically resembles the normal tissue from which it originated. Well-differentiated cancer cells look much like normal cells and tend to grow and spread more slowly than poorly differentiated or undifferentiated cancer cells. Differentiation is used in tumor grading systems, which are different for each type of cancer.1 The most common types of soft tissue sarcomas are described below.2

Malignant Fibrous Histiocvtomas (MFH)/Pleomorphic Sarcomas (PS) Not Otherwise Specified (NOS)

The most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcoma is malignant fibrous histiocytoma, a tumor of the fibrous tissue most often occurring in the arms or legs. The least differentiated of the sarcomas, in many cases it represents a poorly defined, high-grade soft tissue sarcoma that cannot be further defined pathologically (histologically). A recent trend is to classify these poorly differentiated sarcomas as pleomorphic sarcomas or spindle cell sarcomas not otherwise specified (NOS), rather than the previous designation as malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Poorly differentiated sarcomas typically affect older individuals. Analysis of annual rates of MFH and PS reflect this evolving diagnostic trend.

Liposarcomas

The next most commonly encountered and reported soft tissue sarcoma is liposarcoma, a malignant tumor of the fatty (adipose) tissues. This sarcoma also is more common in older persons. There are several subtypes ranging from the low-grade lipoma-like liposarcoma that rarely metastasizes to high-grade pleomorphic liposarcomas and round cell liposarcomas, which have a prognosis similar to malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Liposarcomas can develop anywhere in the body, but they most often develop in the thigh, around the knee, and inside the back of the abdomen. Seen in a wide range of patient ages, liposarcomas occur most frequently in adults between 50 years and 65 years old. Some liposarcomas grow very slowly, whereas others can grow quickly.

Synovial Sarcomas

The third most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcoma is synovial sarcoma, which is more likely to affect younger adults than previously mentioned sarcomas. The most common location is the thigh. Despite the name synovial sarcoma, most do not occur in joints or in the synovium of joints. Synovial sarcomas tend to occur mostly in young adults but can also occur in children and in older people. Many of these cases respond very favorably to chemotherapy with significant shrinkage of the tumor, although resection (surgical removal) and radiation remain the cornerstones of current therapy. Prognosis is similar to malignant fibrous histiocytoma and the other high-grade soft tissue sarcomas mentioned above.

Tumors of Muscle Tissue

Leiomyosarcomas

Smooth muscle (involuntary muscle) cells are found in internal organs such as stomach, intestines, blood vessels, or uterus. This muscle tissue gives these organs the ability to contract involuntarily. Leiomyosarcomas are malignant tumors of involuntary muscle tissue. They can occur almost anywhere in the body, but most often are found in the uterus. A second common site is the retroperitoneum (back of the abdomen) and in the internal organs and blood vessels where leiomyomas (benign version of similar tumor) also arise. Less often, they develop in the deep soft tissues of the legs or arms. They tend to occur in adults, particularly the elderly. Since they often arise from the smooth muscle cells in the walls of arteries, resection of extremity leiomyosarcomas frequently requires a concomitant vascular reconstruction.

Rhabdomyosarcomas

Skeletal muscles are the voluntary muscles that control and allow movement of arms and legs and other body parts. Rhabdomyosarcomas are malignant tumors of skeletal muscle. These tumors commonly grow in the arms or legs, but they can also begin in the head and neck area and in reproductive and urinary organs, such as the vagina or bladder. Rhabdomyosarcomas are primarily tumors of children. Clinically and behaviorally, they are in a class by themselves. They are treated with aggressive chemotherapy, as well as surgery and/or radiation in many cases. The aggressive treatments often cause permanent life-altering disability, even in survivors. For more information, see the American Cancer Society document "Rhabdomyosarcoma [86].“

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Malignant schwannomas, neurofibrosarcomas, and neurogenic sarcomas are malignant tumors of the protective lining that surrounds nerves. The currently favored name for these sarcomas is malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. A rare form of cancer, it often has an association with neurofibromatosis and thus may possess a genetic component.

Tumors of Blood Vessels and Lymph Vessels

Angiosarcomas (Hemangiosarcomas)

Malignant tumors can develop either from blood vessels (hemangiosarcomas) or from lymph vessels (lymphangiosarcomas). These tumors often develop in a part of the body that has been exposed to radiation. Angiosarcomas are sometimes seen in the breast after radiation therapy for breast cancer or in the arm on the same side as a breast that has been irradiated or removed by mastectomy. They are difficult to cure as they spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body and often spread extensively through the local tissues.

Hemangiopericytoma

These are tumors of perivascular tissue (tissue around blood vessels). They most often develop in the legs, pelvis, and retroperitoneum (the back of the abdominal cavity) and are most common in adults. These can be either benign or malignant. They do not often spread to distant sites, tending to recur where they started, even after surgery, unless widely excised. Following recent research and further histologic, genetic, and clinical evaluations, hemangiopericytomas have recently been reclassified as one end of the spectrum of malignant solitary fibrous tumors or possibly identical to malignant solitary fibrous tumors.

Hemangioendothelioma

This is a less aggressive blood vessel tumor than hemangiosarcoma, but still considered a low-grade cancer. It usually invades nearby tissues and sometimes metastasizes to distant parts of the body. It may develop in soft tissues or in internal organs, such as the liver or lungs.

Kaposi Sarcoma

These cancers are composed of cells similar to those lining blood or lymph vessels. In the past, Kaposi's sarcoma was an uncommon cancer mostly seen in older people with no apparent immune system problems. It is now most common in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It also develops in organ transplant patients who are taking medication to suppress their immune system. It is probably related to infection with a virus called human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8).

Tumors of Fibrous Tissue

Fibrous tissue forms tendons and ligaments and covers bones, muscles, and joint capsules, as well as other organs in the body.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)

MFH is found most often in the arms or legs. Less often, it can develop inside the back of the abdomen. This sarcoma is most common in older adults. Although it mostly tends to grow locally, it can spread to distant sites. It is the most commonly diagnosed soft tissue sarcoma, although now these are more often classified as pleomorphic sarcoma, not otherwise specified (NOS), as discussed in the introduction section of soft tissue cancers.

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcomas are cancers of fibrous tissue. They have a characteristic herringbone cloth pattern when viewed under the microscope. Fibrosarcomas most commonly affect the legs, arms, or trunk. They are most common between the ages of 20 years and 60 years, but can occur at any age, even in infancy.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)

These tumors are slow-growing cancers of the fibrous tissue beneath the skin, usually noted in the trunk or limbs. They invade nearby tissues but rarely metastasize. They primarily affect young adults. Due to their slow, insidious growth, their uncommon occurrence, and their innocuous appearance, diagnosis is often delayed. The local recurrence rate is higher than many sarcomas and has been reported to be as high as 50% in some studies. While death due to disease is uncommon (<5%), the local recurrences can cause significant local morbidity.

Fibromatosis/Desmoid tumors

Fibromatosis is one of the names given to neoplastic tumors with features between fibrosarcomas and benign tumors, such as fibromas and superficial fibrous diseases like Dupytren's disease. They tend to grow slowly, but steadily. These tumors are often referred to as desmoid tumors. Although they are benign and do not metastasize, they do form in response to genetic alterations similar to many cancers and can cause great disability and even death. These tumors can invade nearby tissues, causing great havoc and occasionally even death. Some doctors may consider these to be a type of low-grade fibrosarcomas; most, however, regard them as benign but locally aggressive tumors. Certain hormones, particularly estrogen, may increase the growth of some desmoid tumors. There has been a very recent evolution in the thinking about this disease, with an evolution toward a greater role for careful observation after diagnosis, with surgical intervention being less enthusiastically employed, reserving such for more painful and/or aggressively growing tumors. Antiestrogen drugs are sometimes useful in treating desmoids that cannot be completely removed by surgery. Radiation therapy plays a role in treatment, especially when the tumor cannot be resected or in recurrent cases. There are ongoing chemotherapeutic trials in place with newer agents that interrupt the various biological processes in the growth of these tumors that hold promise for future patients. Additional research into the biology and treatment of these, and virtually all tumors, is clearly indicated.

Tumors of Uncertain Tissue Type

Through microscopic examination and other laboratory tests, doctors can usually find similarities between most sarcomas and certain types of normal soft tissues, thus, allowing them to be classified based on this histologic appearance. However, some sarcomas have not been linked to a specific type of normal soft tissue due to their unique appearance that does not closely resemble any normal single tissue type.

Malignant mesenchymoma

These very uncommon sarcomas contain areas showing features of at least two types of sarcoma, including fibrosarcomatous tissue per the original description. Since all connective tissue derive from undifferentiated mesenchymal tissues in an embryologic sense, it has been termed Mesenchymoma. The term has fallen out of favor, and it is now thought that many cases may be better classified as one of the subtypes of sarcomas based on the tissue type contained within the tumor.3

Alveolar soft-part sarcoma

This rare cancer primarily affects young adults. The legs are the most common location of these tumors. One of the most vascular (many tumor-contained and tumor-associated blood vessels) of all sarcomas, it induces an extensive network of vessels to grow in and around the tumor. Because of their very slow growth rate, a delay in diagnosis can occur. Unfortunately, it ultimately has a high mortality rate and can lead to death years after diagnosis. The rate of progression can be quite slow; late metastases are common.

Epithelioid sarcoma

This sarcoma often develops in tissues under the skin of the hands, forearms, feet, or lower legs. Adolescents and young adults are often affected. These are often misdiagnosed as infections and chronic infectious ulcers because of their innocuous appearance and uncommon occurrence. This sarcoma has a much higher propensity for lymph node metastasis than most sarcomas, which usually preferentially metastasize to the lung.

Clear cell sarcoma

This rare cancer often develops in tissues of the arms or legs. It recently has been determined to be a variant of malignant melanoma, a type of cancer that develops from pigment-producing skin cells. How cancers with these features develop in parts of the body other than the skin is not known. As a melanoma, it behaves differently than sarcomas. It has a propensity to spread through the lymphatic system. Local recurrence is common; therefore, wide resections are required for complete local eradication.

Other Types of Sarcoma

There are other types of soft tissue sarcomas, but they are less commonly encountered and not included in this discussion.

A recently published study, based on the National Cancer Database NCDB of the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancers, reports the 13-year experience (1998-2010) with 34 of the most commonly encountered soft tissue sarcomas. This report provides a good overview of the US experience with soft tissue sarcomas, including survival curves, the 2- and 5-year survivorship rate, and various demographic data.4

Soft tissue sarcomas account for less than 1% of all cancer cases diagnosed each year, and for a similar proportion of cancer deaths in any given year.

In terms of case numbers, the musculoskeletal health burden in the United States from soft tissue sarcomas is three to four times greater than that of bone and joint sarcomas. For the period from 2010 to 2014, the annual average number of soft tissue neoplasms, including the heart, approximated 15,500 cases/year in the SEER database. Estimated new cases for 2018 by the American Cancer Society are 13,040.1 Soft tissue sarcomas come in a wide variety of forms that affect different age groups, but the most frequently encountered soft tissue sarcomas affect adults age 45 and older. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11])

As previously noted, the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), a joint program of the Commission on Cancer and the American College of Surgeons, maintains the most thorough database on patients diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas. Although the NCDB was not created to serve as an incidence based registry, it currently gathers data on approximately 72% of the cancers treated in the United States.2 It should be noted this percentage varies from year to year based on the participation and reporting by hospitals to this voluntary database.

A 2014 report by Corey, Swett, and Ward examined the adult cases reported to the NCDB of soft tissue sarcomas during a 13-year interval (1998-2010). In 2010, 5,070 soft tissue sarcomas were reported to the NCDB. While the numbers of soft tissue sarcomas reported to the NCDB increased by 19% over this 13-year period, the number of bone sarcomas reported to the NCDB increased by only 10.7% during this same time.3 However the NCDB is not an incidence or prevalence based database, and the number can simply reflect a change in makeup of the reporting member institutions.

Soft tissue sarcomas can be found among all ages, with the risk of developing soft tissue cancer very small, ranging from 0.33% at 20 years to 0.17% at 75 years of age. However, due to the smaller population count in older cohorts, the share of cases diagnosed after the age of 55 is larger than in younger cohorts. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11], Table 6A.A.1.3.2 PDF [89] CSV [90], and Table 6A.A.1.6.2 PDF [62] CSV [63])

The rate at which males are diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas has historically been higher than for females, with corresponding increases or decreases found in both sexes. The most recent rates from the NCI are for the year 2014 and are 4.1/100,000 for males and 2.9/100,000 for females. Males are diagnosed with soft tissue sarcomas at a slightly higher age than females. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.1.3 PDF [93] CSV [94] and Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Blacks are diagnosed an average of eight years earlier than those who are white. In the 1970s and 1980s, the incidence rates for soft tissue sarcomas was slightly higher among the black population than for the white population. However, in the early 1990s a shift was observed and today incidence rates are higher among whites. In 2014, the rates were 3.5 and 3.3 per 100,000 persons, respectively, for whites and blacks. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53] and Table 6A.A.1.1.4 PDF [95] CSV [96])

The 5-year survival rate in 2010-2014 for soft tissue sarcomas is reported at 64% by the SEER database and an overall relative survival rate of 50% by the American Cancer Society.1 This rate is similar to that for leukemia, colon and rectum, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma cancers. Average length of survival after diagnosis is 5 years, similar to that of breast, colon, and bladder cancers. White women have a slightly higher 5-year survival rate than do men and live an average of 1 year longer after diagnosis. Black women are diagnosed at about the same average age as black men with soft tissue sarcomas but live an average of two years longer after diagnosis. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53]; and Table 6A.A.1.8 PDF [54] CSV [55])

For high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, the most important prognostic factor is the stage at which the tumor is identified. Staging criteria for soft tissue sarcomas are primarily determined by whether the tumor has metastasized or spread elsewhere in the body. Size is highly correlated with risk of metastasis and survival. In general, the prognosis for a soft tissue sarcoma is poorer if the sarcoma is large. As a general rule, high-grade soft tissue sarcomas over 10 cm in diameter have an approximate 50% mortality rate and those over 15 cm in diameter have an approximate 75% mortality rate.

The staging criteria of soft tissue sarcoma of the National Cancer Institute groups sarcomas by whether they are still confined to the primary site (called localized); have spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues (called regional); or have spread (metastasized) to sites away from the main tumor (called distant). The 5-year survival rates for soft tissue sarcomas have not changed much for many years. The corresponding 5-year relative survival rates were:

• 83% for localized sarcomas (56% of soft tissue sarcomas were localized when they were diagnosed)

• 54% for regional stage sarcomas; (19% were in this stage)

• 16% for sarcomas with distant spread (16% were in this stage)

The 10-year relative survival rate is only slightly worse for these stages, meaning that most people who survive 5 years are probably cured.1

Sarcomas are often staged by orthopedic oncologists with a staging system established by Dr. William Enneking and adopted and modified by surgical societies primarily consisting of orthopedic oncologists. That may have accounted for the lack of AJCC staging data in many cases of bone and soft tissue sarcomas reported to the NCDB. Nearly 40% of cases for 2000-2011 reported in the NCDB data have an unknown stage. This is a much higher proportion than found among other common cancer types, making it difficult to compare the severity of soft tissue sarcomas to other cancers.

From 2004-2015 inclusive, information on insurance coverage was available for roughly 65,015 patients treated with soft tissue sarcomas. The largest insurance payer was private insurance (51.0%), followed by Medicare and Medicaid (30.9% and 8.9%) respectively. Other government payors covered 1.4%, while 4.8% were uninsured and payor status was unknown in 3.0%. (Reference Table 6A.B.2.8 PDF [102] CSV [103])

The total economic costs of malignant soft tissue sarcoma are unknown. Surgery is often the first line of treatment for soft tissue sarcoma. Multiple therapies may be needed during the course of the patient's disease, especially in more advanced cases. In later stages of the disease in those not cured with surgery alone, significant costs will accumulate as patients typically develop pulmonary disease and ultimately die. Chemotherapy, and subsequently hormone therapy, immunotherapy, bone marrow transplant, and endocrine treatments are undertaken in a small number of cases that fail standard treatments. Overall, costs will vary with treatments utilized, number, and intensity of treatments, and can easily top $100,000 for a single patient that receives surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. (Reference Table 6A.B.2.6 PDF [76] CSV [77])

Throughout the years 2005--2008, one study reported that the average professional charge for a primary excision was $9,700 and $12,900 for re-excision. Although every 1-cm increase in size of the tumor results in an increase of $148 for a primary excision, size was not an independent factor affecting re-excision rates. The grade of the tumor was positively associated with professional charge, such that higher-grade tumors resulted in higher charges compared to lower-grade tumors. Analysis including professional, technical, and indirect charges revealed that, on average, patients undergoing definitive primary excision at their cancer treatment center were charged $40,230. This compared to $44,770 for patients receiving definitive re-excision of unsuccessful or incomplete previous resections at the same cancer treatment center. This higher cost did not include the charges and costs generated by their previous unsuccessful or incomplete previous attempt at resection.1

This analysis confirms that proper work-up, evaluation, and treatment are key to maintain costs, as well as improve the outcome for these patients. This cost analysis did not include the costs associated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or the costs of diagnostic and follow-up laboratory and radiographic studies, nor the actual costs of care.

The majority of sarcomas develop in people with no known risk factors, and there is currently no known way to prevent these cases. Whereas future developments in genomic research may allow genetic testing to identify persons with increased risk of developing soft tissue sarcomas, few such predictors are available at present. Reporting suspicious lumps and growths or unusual symptoms to a doctor, and appropriate evaluation of such abnormalities can help diagnose soft tissue cancer at an earlier stage. Treatment is thought to be more effective when detected early, as smaller-diameter sarcomas have been shown to have improved outcome compared to large sarcomas.

Whenever physicians examine a patient presenting with a new mass in the leg, thigh, muscles, and deep tissue of the body, particularly if the patient has a previous history of cancer, metastatic cancers in the soft tissues should be considered. The most likely cancers to metastasize to soft tissue are cancers of the lung and kidney.

Cancers of the musculoskeletal system affect both children and adults, but virtually all tumors have different age-based frequency. Myeloma, the cancer of the bone marrow, affects older persons more, while other bone and joint tumors are more prevalent in children and young adults. Soft tissue sarcomas affect all ages, but most are more common as persons reach middle age and later years. See individual cancer discussions for further information. In general, the older the patient, the poorer the prognosis and survival.

Certain primary cancers of bones and joints (adamantinoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and malignant giant cell tumor of bone) are found among people under the age of 30 years in higher proportion than expected for the overall incidence of most sarcomas. In 2010-2014, 42% of bone and joint cancers diagnosed were found in people under the age of 35 years, with more than 26% occurring among children and adolescents under the age of 20. This compares to 4% of all types of cancer sites found in people aged 35 years and younger, and only 1% in those younger than 20 years. Hodgkin lymphoma is the only other cancer to affect young people in similar numbers, with a higher percentage of cases diagnosed in the 20-year to 34-year age range. The average age at diagnosis for bone and joint cancers is 43 years, surpassed in youthfulness only by Hodgkin lymphoma, diagnosed at an average age of 39 years.1 (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11]; Table 6A.A.1.7 PDF [52] CSV [53] ; Table 6A.B.1.3 PDF [20] CSV [21] ; and Table 6A.B.1.5 PDF [106] CSV [107])

Deaths from bone and joint cancers also are more common in people under the age of 35 years. Between 2010 and 2014, 12% of deaths from bone and joint cancer occurred in children and youth under the age of 20, and an additional 15% among young adults aged 20 years to 34 years. The mortality rate among children and youth under 20 years from bone and joint cancer comprises only 0.03% of deaths from all types of cancer, but 10% of cancer deaths in people under the age of 20 years and 5% of deaths among young people aged 20 to 34 years. The relative proportion of deaths from bone and joint cancers was higher in children, youth, and young adults than all other cancer types that disproportionately affect younger people, including brain and nervous system, leukemia, endocrine system, and soft tissue cancers. The average age at death for bone and joint cancers is 61 years, the youngest of all types of cancer. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13]; and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31])

In 2014, osteosarcoma accounted for 55% of the malignant bone tumors in survivors diagnosed with cancer as children and alive on January 1, 2014. Nearly all the remaining bone tumors in survivors diagnosed as children and still alive had been diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma (30%). Among the childhood cancer survivors of all ages, 4.4% were survivors of bone tumors. (Reference Table T6A.A.2.2 PDF [112] CSV [113])

Males were a greater proportion of the osteosarcoma survivors than were females until survivors reached middle age, when females were a larger share. Nearly one in four (22%) of the survivors had been diagnosed some 35 years ago. This is comparable with childhood cancer survivors for all types of cancer, where nearly one in four (23%) were diagnosed more than 30 years ago. (Reference Table 6A.A.2.1 PDF [114] CSV [115])

Although not considered a childhood cancer, soft tissue sarcomas, which affect all ages, accounted for 8% of new diagnoses in the years 2010 to 2014 in children and young adults under the age of 20. Another 9% were found in the population age 20 to 34. Deaths from soft tissue sarcomas in this time frame were slightly lower but still accounted for a higher proportion of cancer deaths in the under 35 population (4% and 6%, respectively) than all except bone and joint cancers. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11] and Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13])

Rhabdomyosarcoma, a soft tissue sarcoma of the muscle mesenchymal cells, accounts for 3.5% of all new childhood cancers among children younger than 15 years and 2.0% of cases for youth aged 15 to 19 years each year. Half of the rhabdomyosarcoma cases are in children age 10 and younger. The 5-year survival rate when detected in children under the age of 15 is now reported at 67%, dropping to 51% for youth aged 15 to 19 years.2 This data demonstrates the relationships of survival to both age and diagnostic subset. In virtually all categories, survival decreases with age advancing beyond 10 years of age. (Reference Table 6A.B.2.3 PDF [116] CSV [117])

Burden of Childhood Musculoskeletal Cancers

The high incidence and mortality rate of bone cancers among children, youth, and young adults creates a significant burden on the productivity and life of future generations. Apart from the financial costs, emotional toil, and lost lives from the initial treatments, survivors carry significant functional burdens and continuing care costs. With no differences found in survival rates between amputation and limb-salvage surgery, up to 90% of surviving bone and joint cancer patients are treated with limb-salvaging surgery.3 These surgeries most often require implantation of massive bone-replacing endoprostheses that have limited life span and compromised function, requiring periodic surveillance and revision surgery to repair or replace worn parts. The amputated survivors will require prosthetic limbs, the function of which is clearly limiting in comparison to normal activity. Furthermore, due to wear and tear of these artificial limbs, as well as changes in the amputated stumps themselves of the survivors’ limbs, these prosthetic limbs will require ongoing costly repairs, revisions, and replacements over the years.

Both procedures are expensive. The cost estimate nearly 20 years ago was $25,000 per year for artificial limb replacement of an amputated limb in an active 20- to 30-year old man in 1997 dollars. The cost estimate was $23,500 for implant, rehabilitation, monitoring, and replacement with limb salvaging endoprostheses.4 A 1994 study comparing hospital and professional fees reported higher costs of $59,214 for the Ilizarov method of limb salvage via lengthening of the remaining parts versus $30,148 for amputation, but cited lifetime prosthetic costs of $403,200.4 Both estimates are limited by sample size and actual knowledge of long-term maintenance costs, but more recent cost estimates are not available. A 2008 study of functional outcome found no clear evidence that one procedure, limb-salvage versus amputation, provided a better functional outcome.5 Due to chronic pain and overall dysfunction, a large number of survivors, regardless of treatment, will end up on disability, requiring public support for the majority of their adult lifetime.

More than 60% of myeloma cases are diagnosed in persons age 65 years and older. This is a similar rate to respiratory and urinary system cancers, both of which disproportionately affect older persons. Soft tissue cancers affect all ages, and in relatively equal proportion in the middle and older years (ages 45 to 84 years). As previously discussed, bone and joint cancers affect a disproportionate number of younger persons and are not considered a major cancer of aging unless in a metastatic form. However, when comparing the share of cases to cohort population size, most cancers have a higher ratio as aging occurs. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.3.1 PDF [10] CSV [11] and Table 6A.A.1.3.2 PDF [89] CSV [90])

Because of the advanced age of many myeloma patients, 78% of deaths from myeloma occur in the 65 and older population. Fewer than 50% of patients survive 5 years after diagnosis, although the long-term survivors skew the average survival time up to 6 years. Soft tissue cancer deaths occur about equally in people under 65 years and those 65 years and older. Deaths from bone and joint cancers have the lowest rate in the 65-year and older population of all cancers since it affects younger persons at a high rate. Again, when compared to the cohort population size, the ratio of deaths increases with age. However, the 2 and 5 year survivorship of both bone and joint as well as soft tissue sarcomas decreases as one ages. (Reference Table 6A.A.1.4.1 PDF [12] CSV [13]; Table 6A.A.1.4.2 PDF [120] CSV [121]; and Table 6A.A.1.5.1 PDF [30] CSV [31])

Burden of Musculoskeletal Cancers of the Aging

The average age of the population in the United States continues to rise. With aging, the human body's ability to cope with stress and illness declines. As a result, poorer outcomes from cancers are expected in the aged due to greater decline in functional status, adaptability, and an increase in co-morbid conditions. All these factors effect survival.

The relative frequency of more common benign bone tumors has been discerned from prior publications and extrapolation from the primary author’s (Ward) case registry of consecutive surgical cases treated between 1991 through 2004. It should be noted that although Dr. Ward's personal tumor registry has been updated since 2004, in 2005 additional providers joined his group and began to share care for this cohort of patients. This, in his opinion, meant accurate incidence estimates could no longer be extrapolated from his personal tumor database. Table 6A.C.1 (PDF [125] CSV [126]) reflects the collected experience reported in the Mayo Clinic publication of 1986, the University of Florida publication from 1983, the J. Mirra experience reported in 1989, and the case series reflecting the practice of Dr. Ward, a full-time solo orthopedic oncologist in practice from 1991 to 2004 at Wake Forest University Health Sciences in Winston-Salem, NC.