[7]

[7]

Demographic shifts have changed the landscape of the United States. The growth in the number and proportion of older adults is unparalleled in US history. Aging baby boomers and longer life spans combined will double the population of older Americans (age 65 years or older) during the next 25 years to about 72 million. By 2030, older adults will account for roughly 20% of the US population.1

During the past century, there has been a change in the leading causes of death for all age groups, including older adults, from infectious diseases and acute illnesses to chronic diseases and degenerative illnesses. Nearly half (42%) of all Americans, and four of every five older Americans, have numerous chronic conditions.2 Treatment for this chronic-conditions population accounts for 90% of the country’s 3.5 trillion annual healthcare expenditures.2, 3

The ability to move (mobility) is essential to everyday life and central to health and well-being among older populations. Impaired mobility is associated with a variety of unfavorable health outcomes. As the proportion of older Americans continues to increase, aging and public health professionals have a role to play in improving mobility for older adults. Gaps exist in the assessment and measurement of mobility among older adults who live in the community, particularly those who have physical disabilities or cognitive impairments.

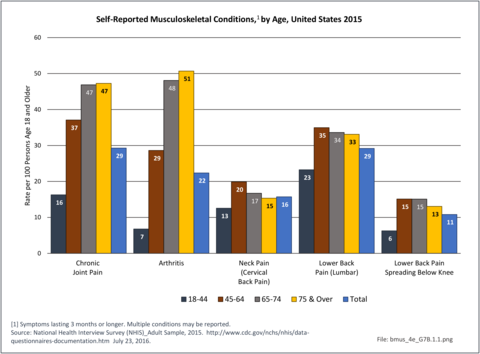

Older adults are prone to higher rates of nearly all musculoskeletal conditions than those found in younger people. In large part, these conditions can be attributed to wear and tear on bones and joints over a lifetime. However, some musculoskeletal conditions such as back pain are equally prominent in younger age populations, particularly those in their middle ages.

Arthritis is self-reported in 2015 at the highest rate among persons aged 75 years and older (51%), but by nearly as many in the 65 to 74-year age range (48%). Only 29% of persons age 45 to 64 years self-report they have a form of arthritis. Chronic joint pain has a similar reporting pattern as arthritis, but with somewhat lower rates – 47% among those 65 and older and 37% by those 45 to 64-years of age. Low back pain, on the other hand, was self-reported at the highest rate by persons aged 45 to 64-years (35%), closely followed by all people age 65 years and older (34%). Overall, 124.6 million people age 18 years and older self-reported one or more types of musculoskeletal conditions in 2015. (Reference Table 7B.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

The most common joint reported by the 73 million people over the age of 18 years with chronic pain in 2015 is the knee (47 million), followed by the shoulder (22 million). However, the rate per 100 persons in the various age groups reporting chronic pain in specific joints varies. Knee pain (32%) and hip pain (14%) are reported at the highest level by those age 75 and older, while shoulder (15%), fingers (15%), ankle (8%), wrist (9%), and toes (6%) are reported highest by persons age 65 to 74. The only site with the highest reported chronic pain by persons age 45 to 64 years is the elbow (7%). All age groups reported chronic pain in a mean of just over two joint sites. Overall, joint pain in the ankle, wrist, elbow, and toes is lower among those in the oldest age group compared to those 45 to 74 years of age, possibly due to this population segment being less active and placing lower stress on these joints. (Reference Table 7B.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

Self-reported limitations in performing activities of daily living from arthritis and back or neck problems affect about one in ten people. Limitations caused by arthritis increase steadily as the populations ages, while back and neck problems are relatively consistent after the age of 45. While overall persons age 18 to 45 reported few limitations, back and neck problems are the most common cause. (Reference Table 7B.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

Bed and Lost Workdays

People age 45 to 64 years accounted for 41% of the 54 million persons age 18 and over who reported bed days in 2015 due to musculoskeletal conditions, but 50% of the total bed days reported taken. A bed day is defined as one-half or more days in bed due to injury or illness, excluding hospitalization. The greater number of total bed days reported by this age group is due to a high mean of 24.8 days per person combined with large share of the population reporting bed days because of a musculoskeletal condition. (Reference Table 7B.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

This same age group also accounted for slightly more than half (51%) of the 36 million lost workdays due to musculoskeletal conditions reported by people age 18 years and older and in the workforce. People aged 65 years and older reported only 6% of total lost workdays because of the low number that are still in the workforce. (Reference Table 7B.1 PDF [4] CSV [5])

Older adults will often experience musculoskeletal diseases affecting the spine, with spondyloarthritis and osteoporosis with vertebral fractures often the cause of pain and functional decline. Seniors with such problems may find themselves unable to push or pull large objects, or at times even to reach above their heads. They may have problems lifting grocery bags from the floor or completing household tasks. Bending at the waist may increase the risk for vertebral fractures in people with osteoporosis, reducing breathing capacity and predisposing older adults to chronic lung disease and pneumonias.

Self-reported back and neck pain rates peaked in the age range of 45 to 64 in 2015 and was reported at slightly lower rates for persons age 65 years and older. More than one in three people age 45 years and older reported back or neck pain. (Reference Table 7B.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

People aged 65 and older had the highest rate of healthcare visits for back and neck pain (43.7 per 100 persons) but accounted for only 26% of the 83 million total healthcare visits for back or neck pain in 2013. The rate of healthcare visits for people age 45 to 64 years was nearly as high (41.0 per 100 persons) and accounted for nearly one-half (48%) of total visits. While only 19.1 in 100 people ages 18 to 44 years had a healthcare visit in 2013 for back and neck pain, this age group comprised 30% of all visits. Total healthcare visits included hospital discharges, emergency department (ED) and outpatient clinic visits, and physician office visits. (Reference Table 7B.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Those aged 45 to 64 years had the highest number of spinal fusion procedures performed for back or neck pain, with one in four, or 25.3%, of hospital discharges in this age group with a back or neck pain diagnosis having had a spinal fusion procedure performed. However, the highest rate of hospital discharges with a fusion procedure was among those under 18 years of age (74%), primarily due to the very small number of discharges for back pain in this age group. (Reference Table 7B.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Most bed days reported due to back pain (90%) are accounted for by people under the age of 65. A higher number of younger people, those aged 18 to 45 years, report taking bed days than those aged 45 to 64, for spine pain. However, because they report a lower mean number of bed days than the older cohort (6.2 days versus 9.0 days) they account for a slightly smaller share of the total bed days for back pain. People aged 65 years and older account for only a small share of the people who report taking a bed day due to spinal pain (5%), but a larger mean number of days (14.9 days). (Reference Table 9B.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

Lost workdays due to spine pain or problems in 2015 were taken primarily by people aged 18 to 64 years (96%), the prime workforce ages, and split nearly equally between those under and over the age of 45 years. In 2015, 264 million workdays were reported lost due to back pain. (Reference Table 9B.2 PDF [16] CSV [17])

This report includes a range of deformity conditions that affect the spine. The most common spinal deformity in older adults is acquired through multiple vertebral fractures resulting in kyphosis. Vertebral fractures are often not clinically identified and may show merely as height loss. Nonetheless, vertebral fractures greatly increase the likelihood of future fractures and mortality.1,2

The most familiar spinal deformity condition is that of curvature of the spine, which includes scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis. In addition to curvature of the spine, other spinal deformity conditions include spondylolisthesis, spinal infections, complications of surgery, and spondylopathies. Of the 23.4 million healthcare visits in 2013 for spinal deformity, 13 million had a diagnosis of spondylopathy, which refers to any disease of the vertebrae or spinal column associated with compression of peripheral nerve roots and spinal cord, causing pain and stiffness.

Two spinal deformity conditions stand out in the 65 and older cohort -- traumatic spinal fractures and curvature of the spine. People aged 65 years and older accounted for the largest share of healthcare visits in 2013 for vertebral compression fractures (49%), even though they represent only 14% of the population. This group also has a higher than expected share of healthcare visits for all spinal deformity diagnoses (32%). Of the 23.4 million visits in 2013 with a diagnosis of spinal deformity, 40% were made by people age 45 to 64 and 25% by those aged 65 and older. (Reference Table 9B.3 PDF [28] CSV [29])

Arthritis is one of the most common chronic conditions found in the US population. It currently affects 54.4 million adults1 and is projected to reach 78.4 million, or 26% of the adult population by 2040.2 Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States and is a major cause of work and activity limitations, which subsequently affects the economy. Pain from arthritis can substantially affect a person’s quality of life.

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC) affect people in higher numbers as they age. Only 7 in 100 persons between the ages of 18 and 44 years report they have doctor-diagnosed arthritis. By the age of 65 years and older, this rate has increased to one in two with some form of arthritis. Although the rates of persons reporting limitations in performing activities of daily living are lower, there is a large disparity between younger persons and the aging. (Reference Table 7B.4.1 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Bed days occur when a person spends at least one-half day in bed in the previous 12 months due to a health condition. On average in the years 2013 to 2015, 607.0 million bed days were reported by persons age 18 years and older due to arthritis. Only 4% of people aged 18 to 44 years reported arthritis-caused bed days. For all people aged 45 years and older, the rate was between 15% and 18%. (Reference Table 7B.4.1 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Arthritis is most likely to be the cause of lost workdays among people between the ages of 45 and 64 years, with nearly 1 in 10 reporting workdays lost. On average in the years 2013 to 2015, 180.9 million workdays were reported lost due to arthritis, with people in the 45- to 64-year age group accounting for 62% of these days. This higher share of lost workdays for this group is likely due to the much higher participation in the workforce for this prime working age cohort. (Reference Table 7B.4.1 PDF [32] CSV [33])

The prevalence of clinically diagnosed symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) was calculated from the National Health Interview Survey 2007–2008 and the proportion with advanced disease (Kellgren-Lawrence grades 3–4) was derived using the Osteoarthritis Policy Model, a validated simulation model of knee osteoarthritis. About 14 million persons have symptomatic knee OA, with advanced OA comprising over half of those cases. This includes more than 3 million African American, Hispanic, and other racial/ethnic minorities. Adults under 45 years of age represented nearly 2 million cases of symptomatic knee OA and individuals between 45 and 65 years of age 6 million more.3

Despite the frequency of severe pain often experienced with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, these illnesses account for only 21% of the nearly 30 million hospital discharges in 2013. Visits to a physician’s office, emergency department, or outpatient clinic account for most healthcare visits related to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (AORC), with nearly 100 million ambulatory visits in 2013. Among the 6.4 million hospital discharges for an AORC in 2013, age was a factor in increasing rates of hospitalization. Fewer than 1 in 100 persons ages 18 to 44 years had a hospital discharge with a diagnosis of an AORC, while 9 in 100 aged 65 years and older were discharged with an AORC diagnosis. However, among all AORC conditions, the distribution of healthcare visits by age varied by age group. (Reference Table 7B.4.2 PDF [42] CSV [43])

Osteoarthritis is the primary form of arthritis to affect older persons and begins to show increasing rates for people in their 40s and 50s. Joint pain, the other common problem, results in healthcare visits among people aged 45 to 64. By the age of 65 years, multiple forms of arthritis are often diagnosed and categorized as other rheumatic conditions. (Reference Table 9B.4.2 PDF [42] CSV [43])

Age is not a factor in the length of hospital stay or mean charges with a diagnosis of an AORC. In general, the type of AORC is also not a factor in length of stay or charges. Hospital charges are a rough estimate of hospital cost, and do not include doctor’s fees. (Reference Table 9B.4.3 PDF [46] CSV [47])

Joint replacement procedures are often performed when arthritis has become severe and debilitating. Most procedures are performed on people aged 65 and over, with the exception of spine replacement procedures. (Reference Table 9B.4.4 PDF [48] CSV [49])

Osteoporosis develops when more bone is lost (resorbed) than is replaced in the normal bone remodeling process. Several factors contribute to the development of osteoporosis, but the exact reason why the remodeling process becomes unbalanced is unknown. Factors that often lead to osteoporosis include aging, physical inactivity, reduced levels of estrogen, excessive cortisone or thyroid hormone, smoking, and excessive alcohol intake. Loss of bone calcium accelerates in women after menopause.

Bone loss occurs most frequently in the spine, lower forearm above the wrist, and upper femur or thigh, the site where hip fractures usually occur.

Osteopenia or low bone mass: A value for bone mineral density more than 1 standard deviation (SD) below the young healthy female adult mean, but less than 2.5 SD below this value.1

Osteoporosis: A value for bone mineral density 2.5 SD or more below the young healthy female adult mean.1

Young female adult mean and standard deviation (SD): For the femoral neck, the mean and SD were based on data for 20- to 29-year-old non-Hispanic white females from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).2 For the lumbar spine, the mean and SD were based on data for 30-year-old white women from the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) densitometer manufacturer.3

Other races: People from racial and ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Mexican American. This group consists primarily of Hispanic descent other than Mexican American, Asian, Native American, and multiracial persons, among others.

Prevalence estimates of osteoporosis or low bone mass at the femoral neck or lumbar spine (adjusted by age, sex, and race/ethnicity to the 2010 Census) for the non-institutionalized population age 50 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2010 US Census population counts to determine the total number of older US residents with osteoporosis and low bone mass. There were over 99 million adults 50 years and older in the US in 2010. Based on an overall 10.3% prevalence of osteoporosis, the authors estimated that in 2010, 10.2 million older adults had osteoporosis. The overall low bone mass prevalence was 43.9%, from which they estimated 43.4 million older adults had low bone mass. Of these, 7.7 million were non-Hispanic white (prevalence of 10.2%), 0.5 million non-Hispanic black (prevalence of 4.9%), and 0.6 million Mexican American adults (prevalence of 13.4%) had osteoporosis and another 33.8 million, 2.9 million, and 2.0 million had low bone mass (prevalence 44.9%, 29.7%, and 43.2%), respectively. 4 (Reference Table 7B.5.1 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Osteoporosis often is not the principal diagnosis code related to a healthcare visit because the condition is usually an underlying cause of another condition, particularly fragility fractures that often occur after a fall or other seemingly minor incident. Often in such healthcare visits, osteoporosis may not even be listed as a condition. Still, in 2015, primary osteoporosis was listed in 1.87 million hospital discharges and emergency department visits as a reason for the visit in the population aged 50 and over. Fragility fractures occurred in 1.48 million visits for people aged 50 years and older. (Reference Table 7B.5.1 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Age is a factor in both primary osteoporosis diagnosis and in the occurrence of fragility fractures with most occurring in people after the age of 70. A prior fracture in women aged 50 years and older is the most important risk factor for hip fractures. More than three-fourths (76%) of primary osteoporosis diagnoses were for people ages 70 years and older. However, in 2013, 8% of osteoporosis diagnoses was for people aged 50 to 59 years, and 16% among those aged 60 to 69 years.

Among fragility fractures, 79% were for people aged 70 years and older, with the remainder split among those aged 50 to 69. The site of the fracture was particularly important with respect to age. The oldest group, those 70 years and older, were prone to fractures of the hip and vertebrae. Fractures of the wrist and ankle or foot occurred across all people over the age of 50. (Reference Table 7B.5.1 PDF [52] CSV [53])

Approximately 30% of older women will fall annually, and this risk may be higher in women with other chronic conditions.5,6 Several studies have used survey data to analyze falls, while other studies have limited their analysis to falls seen in emergency departments, in older women, or falls that resulted in fracture or hip fracture.

Falls prevalence may vary by race/ethnicity. In a survey-based cross-sectional study of self- reported falls from 6,277 women 65–90 years of age. The independent association of race/ethnicity and recent falls was examined, adjusting for known risk factors. Compared to whites, Asian (OR 0.64, CI 0.50–0.81) and black (OR 0.73, CI 0.55–0.95) women were much less likely to have ≥1 fall in the past year, adjusting for age, comorbidities, mobility limitation and poor health status. Asians were also less likely to have ≥2 falls (OR 0.62, CI 0.43–0.88). This may contribute to their lower rates of hip fracture.7

Fractures are associated with significant increases in health services utilization compared to pre-fracture levels. Relative to the prior 6-month period, rates of acute hospitalization are between 19.5 (distal radius/ulna) and 72.4 (hip) percentage points higher in the 6 months after fractures. Average acute inpatient days are 1.9 (distal radius/ulna) to 8.7 (hip) higher in the post-fracture period. Fractures are associated with large increases in all forms of post-acute care, including post-acute hospitalizations (13.1% to 71.5%), post-acute inpatient days (6.1% to 31.4%), home healthcare hours (3.4% to 8.4%), and hours of physical (5.2% to 23.6%) and occupational therapy (4.3% to 14.0%). Among patients who were initially community dwelling at the time of the initial fracture, 0.9% to 1.1% were living in a nursing home 6 months after the fracture. These rates rose by 2.4% to 4.0% one year after the fracture.8

Since 1980, there has been a nearly 15% decrease in the prevalence of chronic disability and institutionalization among people aged 65 years and older. A reduction in disability translates directly into cost savings since it is seven times more expensive to care for a disabled senior versus a healthy one. Major activity limitations are a common cause of nursing home admissions. While the most common cause of limitations is arthritis, affecting nearly 50% of people older than 65 years and an estimated 60 million by 2020.9

Vertebral and hip osteoporotic fractures result in a 20% increase in mortality, usually observed in the 12 months after the fracture. Men, who are generally older at the time of the hip fracture, have a 30% mortality rate after the fracture. Moreover, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease contribute to a higher mortality rate.

A population-based study in Olmsted County, MN, found that within the first seven days after hip fracture repair, 116 (10.4%) of participants experienced myocardial infarction and 41 (3.7%) subclinical myocardial ischemia. Overall, the 1-year mortality was 22%, with no difference between those with subclinical myocardial ischemia and those with no myocardial ischemia. One-year mortality for those with a myocardial infraction was significantly higher (35.8%) than for the other two groups.10 The relative mortality after vertebral fracture varies from 1.2 to 1.9 in different reports,3,11 but the excess deaths occur late, rather than early, after vertebral fractures.12

For older adults, falls and associated injuries threaten health, independence, and quality of life. More than a third of people aged 65 years and older who live independently fall each year; falls are the leading cause of injury-related deaths and hospital emergency department visits.

On average, more than 8.7 million injury episodes, of which 3.1 million were fall related, for which people sought medical treatment were self-reported by individuals in 2013-2015. The majority of injuries occurred to people between the ages of 18 and 64 years, the ages that comprised 83% of the over-18-year population in the United States. Sprains and strains (31%) were the most frequent injury reported for which medical care was sought, but 18% suffered fractures, 18% severe contusions, and 14% open wounds.

Falls are the primary cause of musculoskeletal injuries as the population ages. Approximately three out of four injuries among people aged 65 years and older for which a person is hospitalized or visits an emergency department is the result of a fall. Trauma, such as auto accidents and other accidents involving machinery or moving objects, is a major cause of musculoskeletal injuries among people ages 18 to 44 years, particularly for injuries where care is received in an emergency department. Other causes of injuries, including sports injuries, are seen in emergency departments for one in three (33%) injuries to people aged 18 to 44 years and one in two (51%) for people under the age of 18. (Reference Table 9B.6 PDF [63] CSV [64])

Osteogenic sarcoma (OS) exhibits a bimodal distribution, the significant second peak in incidence occurs in the seventh and eighth decades of life. Osteosarcoma in the elderly can also be attributed to Paget’s disease or previous radiotherapy. The expectation that these elderly patients may not tolerate aggressive modern chemotherapy means that those patients who develop OS after the age of 40 years are excluded from current trials of treatment. As a result, remarkably little is known about the outcome for this age group.1

The overall incidence of tumors of the musculoskeletal system is lower than many types of cancers. This is particularly true for primary cancers of the bones and joints, although bones and joints are frequently a site of secondary, or metastasized, cancers. The occurrence of cancers of the bones and joints affects all ages and is one of the primary cancers in young people. Myeloma, cancer of the bone marrow, is a disease of the elderly, with nearly two-thirds of cases found in persons age 65 and over. Soft tissue cancers affect all ages, but the occurrence increases with age. (Reference Table7B.7 PDF [67] CSV [68])

Key challenges in the area of musculoskeletal health in older adults are significant. Along with the dramatic increase in the number of older adults is the expectancy that healthy adults will maintain mobility and activity. However, prolonged life expectancy and years of stress on bodies is greatly increasing the likelihood of development of arthritis and osteoporosis, among other conditions, over the years. These conditions often lead to pain, disability, and reduce the ability to remain active and perform activities of daily living. New research to address causes and reduce disability caused by conditions common in the aging population is needed.

A growing body of work on health-related knowledge translation1 reveals significant gaps between what is known to improve health, and what is done to improve health.

A gap in medical care continues to occur after an osteoporosis related fracture in older adults. Furthermore, the decreasing rate of treatment for osteoporosis after hip fracture is noted in the US by Solomon and colleagues.2 The latest quality measures by the National Commission on Quality Assessment (2017) indicate that treatment for osteoporosis after a fracture in an older woman has increased. Evaluation measured as a bone density test is performed in 72.7% of health management organizations (HMOs) and 82% of Preferred Provider Organizatons (PPO). Actual osteoporosis treatment is reported as 46.7% of HMOs and 39.1% of PPOs. This is a substantial increase over prior annual findings.

System-based quality improvement programs such as the American Orthopaedic Association’s “Own the Bone [71]” have been successful with raising awareness and spearheading improvement in increasing treatment rates for osteoporosis after a fracture.3,4,5

Another area with a gap in medical care is in the prevention in falls. Falls are common in older individuals, affecting as many as 30% of older women. Injuries from falls include fractures and blunt head trauma, and result in increased mortality. Women with self-reported osteoarthritis (OA), in particular, have an increased risk of falls, and in spite of elevated bone mass, remain at risk of fractures.6 In 2017, the cost of fall injuries totaled as much as $49.5 billion, depending on methods used to identify a fall, the national healthcare database used, and study design.7 As the population ages, the financial toll for older adult falls is projected to reach $67.7 billion by 2020.8

Falls result in more than 2.8 million injuries treated in emergency departments annually, including over 800,000 hospitalizations and more than 21,000 deaths. Every 11 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency room for a fall. Every 19 minutes, an older adult dies after a fall.8

In conclusion, musculoskeletal disorders are prevalent, and often of serious consequences in older adults. A greater awareness in osteoporosis care after a fracture can be helped through bone density testing. The use of osteoporosis therapy afater fracture will result in a higher quality of life and prevention of disability among America’s seniors.

Links:

[1] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html

[2] https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL221.html

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm#ref1

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.1.pdf

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.1.csv

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b11png

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.1.1.png

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b12png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.1.2.png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b13png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.1.3.png

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b14png

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.1.4.png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b15png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.1.5.png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.2.pdf

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.2.csv

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b21png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.2.1.png

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b22png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.2.2.png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b23png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.2.3.png

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b24png

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.2.4.png

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b25png

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.2.5.png

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.3.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.3.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b31png

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.3.1.png

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.1.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.1.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b41png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.1.png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b42png

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.2.png

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b43png

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.3.png

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b44png

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.4.png

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.2.pdf

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.2.csv

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b45png

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.5.png

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.3.pdf

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.3.csv

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.4.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.4.4.csv

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b46png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.4.6.png

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.5.1.pdf

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.5.1.csv

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b51png

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.5.1.png

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b52png

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.5.2.png

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b53png

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.5.3.png

[60] http://www.who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf

[61] http://www.agingsociety.org/agingsociety/publications/chronic/index.html

[62] http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/adulthipfx.html

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.6.pdf

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.6.csv

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b6png

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.6.png

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.7.pdf

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_t7b.7.csv

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmus4eg7b7png

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_g7b.7.png

[71] https://www.ownthebone.org/

[72] https://www.ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get-the-facts/falls-prevention-facts/