[4]

[4]

Traumatic injury is a term which refers to physical injuries of sudden onset and severe enough to require immediate medical attention. Traumatic injuries are the result of a wide variety of blunt, penetrating, and burn mechanisms. They include motor vehicle collisions, sports injuries, falls, natural disasters, and a multitude of other physical injuries which can occur at home, on the street, or while at work and require immediate care. Persistent pain and psychological distress lasting several years are common after traumatic musculoskeletal injury (TMsI).1

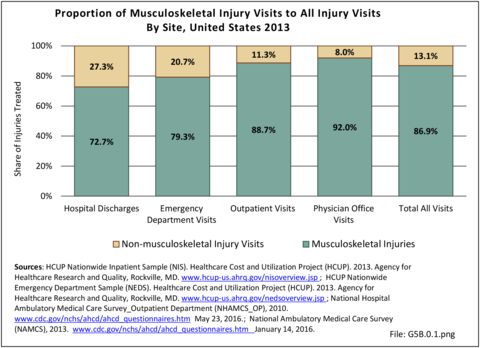

Accidents resulting in traumatic injury and requiring medical attention are treated in all levels of care sites, including physician’s offices, outpatient clinics, hospital emergency departments, and if severe enough, hospitalization. In 2013, more than 72 million patient visits for injuries were recorded for all levels of care, with 87% of these visits (62.7 million) involving a musculoskeletal injury. Visits for musculoskeletal injuries represented 5% of all healthcare visits for any cause. Visits to a physician’s office accounted for the largest share of total musculoskeletal injury healthcare visits (58%), while the 18.9 million emergency department visits for a musculoskeletal injury represented the highest share of visits for any cause (14%). (Reference Table 5B.0.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Records of patient visits for treatment of injuries often include a general cause of injury. In 2013, 28.3 million injury healthcare visits to hospitals and emergency departments were recorded, of which 73% (20.5 million) were musculoskeletal injuries. More than one-half ( 52%) of musculoskeletal hospital injuries were due to falls, with approximately one-fourth each due to trauma events (auto, train, boat, plane, motorcycle) or machinery, moving objects, other types of traumatic injury and other/undefined causes. Only a small proportion (3%) were due to sports injuries. Due to some admissions with multiple causes listed, percentages total more than 100%. Among emergency department visits, more than one-half of musculoskeletal injury visits were due to trauma events (51%), followed by falls as the cause of injury (36%), other/undefined cause (14%) and sports injuries (8%). (Reference Table 5B.1.1 PDF [6] CSV [7])

By sex, women are more likely to suffer a musculoskeletal injury for which healthcare is sought due to a fall, while men are more likely suffer an injury from a traumatic event or a sports injury. Age is a clear factor related to musculoskeletal injuries where hospitalization occurs, with 71% of hospitalization discharges due to an injury from a fall among those age 65 and over. Injuries from falls treated at emergency departments are spread among all age groups. Persons age 18 to 44 years represent the largest share of trauma injuries treated in both the hospital (36%) and emergency department (47%). (Reference Table 5B.1.2 PDF [10] CSV [11]and Table 5B.1.3 PDF [12] CSV [13])

The most frequent type of injury treated as a result of a fall is a fracture, accounting for 80% of hospitalizations and 33% of emergency department visits. Fractures are also the most frequent traumatic injury seen in hospital cases (63%), but open wounds (28%) and sprains/strains (25%) are treated more frequently in the emergency department as a result of a traumatic injury. Sports injuries are tracked in the ED setting, but not the hospital. Sprains and strains accounted for 35% of sports injuries treated in the emergency department in 2013. (Reference Table 5B.1.4 PDF [18] CSV [19])

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also provides data on the cause of injuries in their Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System [24] (WISQARS). Again, falls are the leading cause of unintentional nonfatal injuries (32%), with a rate of 29.2 injuries per 1,000 persons in 2015. The rate rises to 63.6/1,000 among those age 65 and over. Other common causes of unintentional injuries are struck by/against (14%) and overexertion (11%). (Reference Table 5B.1.5 PDF [25] CSV [26] and Table 5B.1.6 PDF [27] CSV [28])

Healthcare visits for treatment of musculoskeletal injuries include hospital discharges, emergency department visits, outpatient clinic visits, and physician’s office visits. Overall, 1 out of every 15 healthcare visits (6.8%) is for treatment of a musculoskeletal injury. In 2013, sprains and strains and fractures were the most frequently treated type of musculoskeletal injury. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [33] CSV [34])

Female injured are slightly more likely to be treated in a hospital than male (55% vs 51% of the population). Persons age 65 and over are far more likely to be treated for a musculoskeletal injury in the hospital, while those aged 45 to 64 are more likely to visit a physician’s office. Non-Hispanic whites are treated for musculoskeletal injuries in all healthcare settings more than other racial/ethnic groups. Residents of the Midwest region visit outpatient clinics for injury treatment more than residents of other regions, while those living in the West are most likely to visit a physician’s office for injury healthcare. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [33] CSV [34]; Table 5B.2.2 PDF [37] CSV [38]; Table 5B.2.3 PDF [39] CSV [40]; Table 5B.2.4 PDF [41] CSV [42])

Nearly 6 in 10 ( 58%) of musculoskeletal injuries for which healthcare treatment was sought were treated in a physician’s office. An additional 3 in 10 were treated in an emergency department and another 1 in an outpatient clinic. Less than 3% were severe enough to require hospitalization. (Reference Table 5B.2.5 PDF [43] CSV [44])

Three out of four (74%) fracture injuries admitted to the hospital are the admitting (first) diagnosis, while one in five other injuries are diagnosed as the admitting diagnoses. The ratio is much higher as the first diagnosis when treated in the emergency department. (Reference Table 5B.3 PDF [47] CSV [48])

Fractures are one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries, and can have long-term impact, particularly among the elderly. In 2013, one in five (24%) musculoskeletal injuries treated in a healthcare facility was for a fracture, with 1 in 20 persons in the population receiving care for a fracture. Data are based on visits in multiple settings and do not represent unique cases. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [33] CSV [34])

Trends in the number of fractures treated between 1998 and 2013 show relatively stable numbers. Around 3 million fractures of the upper and lower limbs are treated in emergency rooms each year, another 9 million in physician’s offices, with about 900,000 upper and lower limb fracture patients hospitalized each year. (Reference Table 5B.5.1 PDF [51] CSV [52])

Fractures of the radius and ulna (lower arm) are the most frequently treated fracture, with 2.7 million treated in 2013. These fractures are usually treated in the emergency department (ED) or a physician’s office, with a third (33%) occurring in the under 18 years of age population. Fractures of the ankle, humerus (upper arm), hand, and foot each account for 1.2 million to 1.6 million of fractures treated. These fractures occur at all ages, but more often in the middle ages of 18 to 64 years. Fracture of the neck of the femur, a serious injury with 77% occurring to persons over age 65 and more often among women, accounting for 68% of first line visits in the hospital or emergency department. Nearly 1.2 million neck of femur fractures visits were treated in 2013, with more than one-half (56%) seen initially in the ED or the hospital. (Reference Table 5B.5.2 PDF [55] CSV [56])

In 2013, fractures of the lower limb first treated in the ED had a higher rate of transfer to the hospital (35%) than did upper limb fractures (10%). This is likely due to neck of femur fractures in the older population, as 66% of lower limb fractures for persons age 65 and older treated in the ED were transferred to the hospital. However, fractures to the trunk were the most serious, and 42% treated in the ED were transferred to the hospital. When hospitalized fracture patients were discharged, more than 1 in 2 (58%) with a lower limb fracture were discharged to skilled nursing, intermediate care, or another facility, while another 11% had home healthcare. Among discharged patients age 65 and over, 80% with a lower limb fracture went to additional care while 8% had home healthcare. (Reference Table 5B.5.3 PDF [59] CSV [60]; Table 5B.5.4 PDF [61] CSV [62])

Sprains and strains are the most common musculoskeletal injuries treated in any healthcare facility. In 2013, one in five (26%) musculoskeletal injuries treated in a healthcare facility was for a sprain or strain, with 1 in 18 persons in the population receiving care for a sprain or strain. (Reference Table 5B.2.1 PDF [33] CSV [34]) Sprains and strains occur on a wide continuum of severity, and while mild sprains can be successfully treated at home, severe sprains sometimes require surgery to repair torn ligaments.

In 2013, sprains and strains of the back and sacroiliac joint comprised nearly one-third (30%, 7.1 million treatment episodes) of all sprains and strains for which healthcare treatment was given. Most were seen in a physician’s office (71%), with nearly all the remaining persons seen in an emergency department. Approximately 11,000 sprains and strains of the back and sacroiliac joint required hospitalization. Slightly more than 5 million sprains and strains of the shoulder and upper arm were seen by healthcare providers, as were 4.2 million sprains and strains of the ankle and foot. All totaled, more than 24 million persons with sprains and strains received medical care for these injuries in 2013. (Reference Table 5B.6.1 PDF [65] CSV [66])

When evaluated by age, in 2013 more sprains and strains were treated in persons aged 18 to 44 years than other age groups, followed by the 45 to 64 years of age group. Although there is some difference by sex, overall sprain and strain injury treatments reflect the distribution of male and female individuals in the population. The one exception is the 58% of hospital treatment for sprains and strains of the knee and leg which affect more male individuals. (Reference Table 5B.6.2 PDF [69] CSV [70])

Penetrating trauma is an injury caused by a foreign object piercing the skin, which damages the underlying tissues and results in an open wound. The most common causes of such trauma are gunshots, explosive devices, and stab wounds. Depending on the severity, it can be a puncture wound (sharp object pierces the skin and creates a small hole without entering a body cavity, such as a bite), a penetrating wound (a sharp object pierces the skin, creating a single open wound, AND enters a tissue or body cavity, such as a knife stab), or a perforating wound (object passes completely through the body, having both an entry and exit wound, such as a gunshot wound).

The most common causes of penetrating trauma in the US are gunshots and stabbings. One recent study found approximately 40% of homicides and 16% of suicides by firearm involved injuries to the torso.1 As recently as 2003, the US led in firearms-related deaths in all economically developed countries.2

A 2010 study of 157,045 trauma patients treated at 125 US trauma centers found the incidence of penetrating trauma to be significantly less than blunt trauma. Only 6.4% of all injuries were gunshots, while 1.5% were stab wounds.3 Yet, significant geographic variations and racial differences in the incidence of penetrating trauma exist. In a Los Angeles study of 12,254 trauma patients, 24% of patients treated had sustained penetrating trauma. In a similar Los Angeles study, penetrating trauma accounted for 20.4% of trauma cases, yet resulted in 50% of overall trauma deaths—most of which were due to gunshot wounds.4 Hence, the precise incidence of penetrating chest injury varies depending on the urban environment and the nature of the review. Overall, reported findings show penetrating chest injuries account for 1% to 13% of trauma admissions, and acute exploration is required in 5% to 15% of cases; exploration is required in 15% to 30% of patients who are unstable or in whom active hemorrhage is suspected.5

Although hospital and emergency department visits for penetrating injuries are a small proportion of total visits (<1%), in 2013 there were 76,000 hospital discharges and 290,400 emergency department (ED) visits with an external cause of injury defined as assault by firearms, explosives, or cutting/piercing instrument. Cutting/piercing instruments were identified for about two-thirds of the injuries (45,500 hospital discharges and 19,300 ED visits). Most of the remaining cases listed a firearm cause. (Reference Table 5B.7.1 PDF [73] CSV [74])

Males constituted a majority of persons with penetrating injuries, particularly when caused by firearms (88%) and explosives (80-85%). Two-thirds of penetrating injuries (66%-67%) occurred to persons age 18-44, even though this age group represents on 36% of the population. Residents in the South region had slightly higher rates of penetrating injuries than representative of its population. (Reference Table 5B.7.1 PDF [73] CSV [74])

Looking at a five-year trend for penetrating injuries by race shows black, non-Hispanics carry a larger share of firearms injuries than expected for the population share, but only a slightly higher share of injuries caused by explosives or cutting/piercing instruments. (Reference Table 5B.7.3 PDF [79] CSV [80])

Hospital charges to treat injuries from firearms ($102,300) and explosives ($12,600) are much higher, on average, than the cost for all musculoskeletal injuries or all hospital discharges. Average charges for stabbing injuries ($35,400) are lower than for other causes of hospital stay. Overall in 2013, penetrating injuries accounted for $4.8 million in hospital charges. (Reference Table 5B.7.2 PDF [83] CSV [84])

The average hospital length of stay for musculoskeletal injuries in 2013 was 5.4 days, nearly a full day longer than for hospital discharges for any diagnoses (4.6 days). Persons age 45 to 64 had a slightly longer average stay (5.6 days), while those under 18 years of age had the shortest stay (4.3 days).

Dislocation injuries serious enough to require hospitalization had the longest average length of stay in 2013, nearly six days. However, except for serious sprains and strain injuries, with an average stay of just under five days (4.8), all musculoskeletal injuries had an average hospital stay of five to five-and-one-half days.

Average charges to treat musculoskeletal injuries provide a comparison between injury type and groups, but do not necessarily reflect actual cost as these are usually negotiated between providers and payors. By age, the highest average charges are for persons age 18 to 44 years ($64,700 per stay). The lowest charges are for the youngest patients (under 18 years, $47,400) and those age 65 and over ($51,000). By type of injury, dislocations have the highest average charges ($74,000 per episode), followed by fractions ($61,900). Musculoskeletal injuries have average hospital charges of $15,000 more than hospital stays for any diagnoses ($55,700 vs. $39,500). (Reference Table 5B.4.1.2 PDF [90] CSV [91])

In general, the average length of stay and average charges for persons hospitalized with a musculoskeletal injury are longer/higher for men than for women, with the exceptions of fractures and contusions. Overall, non-Hispanic blacks have slightly longer hospital stays for musculoskeletal injuries, while Hispanics have higher average charges. By geographic region, the Northeast and South have slightly longer average stays, but the highest average charges are in the West. Fractures account for more than half the total charges for musculoskeletal injuries. (Reference Table 5B.4.1.1 PDF [96] CSV [97]; Reference Table 5B.4.1.3 PDF [98] CSV [99]; Reference Table 5B.4.1.4 PDF [100] CSV [101])

Total charges for all persons hospitalized with a musculoskeletal injury diagnoses (6.3%) comprise a larger share of total hospital charges for all discharges with any diagnoses than the comparative share of patients (4.5%). The discrepancy from 0.5% to 4.1% and is greatest for persons age 45 to 64. (Reference Table 5B.4.1.1 PDF [96] CSV [97]; Reference Table 5B.4.1.2 PDF [90] CSV [91]; Reference Table 5B.4.1.3 PDF [98] CSV [99]; Reference Table 5B.4.1.4 PDF [100] CSV [101])

Musculoskeletal injuries treated in an emergency department (ED) are usually discharged to home (90%), but nearly one in ten is admitted to the hospital (8%). This is half the rate seen for all other diagnoses presenting to the ED (16%). However, persons treated in a hospital for a musculoskeletal injury are more likely to be discharged to additional care (55%), including short-term, skilled nursing/intermediate care, or home health care, than are hospital discharges for any diagnoses (30%). (Reference Table 5B.4.2 PDF [106] CSV [107]; Table 5B.4.3 PDF [108] CSV [109])

The type of musculoskeletal injury impacts whether additional care is likely to be required, with fracture injuries more often discharged to additional care than other types of musculoskeletal injuries. One in for (25%) of persons with fracture injuries seen in the ED are admitted to the hospital.

Age is a significant factor related to additional care. Among those under the age of 18, 91% are discharged from the hospital to home. By the age of 65 and over, 81% are discharged to skilled nursing/intermediate care or home health care with a fracture. This compares to 25% of hospital discharges for any diagnoses.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.0.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.0.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b01png

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.0.1.png

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3555553/pdf/jpr-6-039.pdf

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.1.pdf

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.1.csv

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b11png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.1.png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.2.pdf

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.2.csv

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.3.pdf

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.3.csv

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b121png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.2.1.png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b122png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.2.2.png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.4.pdf

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.4.csv

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b131png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.3.1.png

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b132png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.3.2.png

[24] https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates.html

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.5.pdf

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.5.csv

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.6.pdf

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.1.6.csv

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b141png

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.4.1.png

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b142png

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.1.4.2.png

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.1.pdf

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.1.csv

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b211png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.1.png

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.2.pdf

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.2.csv

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.3.pdf

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.3.csv

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.4.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.4.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.5.pdf

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.2.5.csv

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b212png

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.2.png

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.3.pdf

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.3.csv

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b213png

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.2.1.3.png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.1.pdf

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.1.csv

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b511png

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.1.png

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.2.pdf

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.2.csv

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b512png

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.2.png

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.3.pdf

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.3.csv

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.4.pdf

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.5.4.csv

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b513png

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.1.3.png

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.1.pdf

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.1.csv

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b521png

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.2.1.png

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.2.pdf

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.6.2.csv

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b522png

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.2.2.png

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.1.pdf

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.1.csv

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b531png

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.1.png

[77] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b532png

[78] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.2.png

[79] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.3.pdf

[80] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.3.csv

[81] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b533png

[82] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.5.3.3.png

[83] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.2.pdf

[84] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.7.2.csv

[85] https://www.jems.com/articles/print/volume-37/issue-4/patient-care/penetrating-trauma-wounds-challenge-ems.html

[86] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b31png

[87] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.1.png

[88] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b32png

[89] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.2.png

[90] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.2.pdf

[91] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.2.csv

[92] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b33png

[93] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.3.png

[94] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b34png

[95] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.4.png

[96] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.1.pdf

[97] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.1.csv

[98] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.3.pdf

[99] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.3.csv

[100] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.4.pdf

[101] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.1.4.csv

[102] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b35png

[103] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.5.png

[104] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b36png

[105] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.3.6.png

[106] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.2.pdf

[107] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.2.csv

[108] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.3.pdf

[109] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_4e_5b.4.3.csv

[110] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b41png

[111] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.4.1.png

[112] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b42png

[113] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.4.2.png

[114] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b43png

[115] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.4.3.png

[116] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5b44png

[117] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5b.4.4.png