[2]

[2]

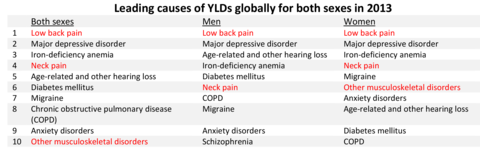

Worldwide declining death rates are rapidly bringing nonfatal diseases and injuries to the forefront of health concerns. As people live longer, more years are spent with disabling and life restricting diseases, including musculoskeletal diseases. Globally, life expectancy at birth in 2015 was 68.6 years,1 and 79.8 years in the US.2 By 2050, life expectancy worldwide is expected to rise to 76.2 years,1 and may be as long as 85.9 years and 93.3 years for males and females, respectively, in the US based on current improvements in health care.3 The most recent Global Burden of Disease Study4 has noted that “as countries around the world have made great progress in addressing fatal diseases, nonfatal diseases pose the next major threat in terms of disease burden.” Leading causes of years lived with disability (YLD) for both men and women include major musculoskeletal conditions.

Musculoskeletal conditions are among the most debilitating nonfatal health diseases. Persons affected with back pain and arthritis have high rates of chronic pain and disability, reducing the quality of life and limiting ability to participate in many common activities. More than one-half of the US population experience these conditions.

The Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States, successor to Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States published by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (1992 and 1999), was first produced in print in 2008 as part of the United States Bone and Joint Decade, 2002-2011. The national recognition of musculoskeletal conditions as one of the most disabling and costly conditions experienced by Americans was proclaimed in March 2002 by then President George W. Bush.5,6 At the end of the decade, the multiple associations of health providers treating musculoskeletal diseases realized the work had only begun, and the United States Bone and Joint Initiative (USBJI), a part of the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health, was created. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States was updated in 2011, again in print. In 2014, the first electronic edition was completed. Future years will see individual chapter updates rotating in 2 to 3 year cycles.

The goal of USBJI is to improve the quality of life for people with musculoskeletal conditions and to advance understanding and treatment of these conditions through research, prevention, and education. The cornerstone of USBJI is describing the burden of musculoskeletal disease, defined as the incidence and prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions; the resources used to prevent, care, and cure them; and the impact on individuals, families, and society. Direct costs of the burden of musculoskeletal disease include hospital inpatient, hospital emergency and outpatient services, physician outpatient services, other practitioner services, home health care, prescription drugs, nursing home cost, prepayment, and administration and non–health-sector costs. Indirect cost relates to morbidity and mortality, including the value of productivity losses due to disability or premature death due to a disease, the value of lifetime earnings due to disability or early death, and the impact of the conditions on quality of life.

With the aging of the US population, musculoskeletal impairments and disability will become an increasing large burden as they are most prevalent in the older segments of the population. Using US Census Bureau projections, by the year 2060, the number of individuals in the United States older than the age of 65 years is projected to grow from the current 15% (47.8 million) of the population to 24% (98.2 million). Persons age 80 years and older will double from the current <4% to more than 8%.7 Looking at projections from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network utilizing improved healthcare treatments, by 2050, the population age 65 and older would be between 99.3 and 107.7 million, while the population age 85 and older would number 27.0 to 34.7 million.3

Regardless of the projection method, the share of the population age 65 and over, those most likely to suffer from musculoskeletal diseases, is projected to increase rapidly in the next few decades. Health care services worldwide will be facing severe financial pressures in coming decades unless new treatments or means of prevention are found to address the escalating number of people affected by musculoskeletal diseases.

The following pages on this website, provide data to support research, education programs, and healthcare policy research that will bring about significant advances in the knowledge, diagnosis, and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, with the goal of improving treatment to reduce pain and disabilities brought on by chronic musculoskeletal diseases.

As noted previously, great progress in addressing fatal diseases is being made worldwide and nonfatal diseases pose the next major threat in terms of disease burden. Musculoskeletal conditions – in particular, trauma, back pain, and arthritis – constitute a major share of this morbidity burden, often restricting activities of daily living, causing lost work days, and are a source of lifelong pain. In spite of this, research funding to ease this burden remains well below that of other disease conditions.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine wrote “In setting national priorities, NIH (National Institutes of Health) should strengthen its analysis in the use of health data, such as burdens of disease, and of data on the impact of research and the health of the public.”1 The Global Burden of Disease has identified low back pain, neck pain, and other musculoskeletal conditions as three of the top ten leading causes for years lived with disability.2 By current US estimates, more than 78% of the persons age 18 years and older reporting a disabling condition reported a musculoskeletal disorder. (Reference Table 1.5.1 PDF [11] CSV [12]) Yet, research funding to alleviate these major health conditions remains substantially below that of other major health conditions such as cancer, respiratory, and circulatory (eg, heart) diseases. (Reference Table 1.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) was formed in 1987. Across the years, research funding for NIAMS has declined in relative terms, and since 2000, less than 2% of the annual National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget has been appropriated to musculoskeletal disease research. In fact, the funding share for 2016 was the lowest it has ever been, at 1.68% of the total NIH budget.

Over the last five years (2012 to 2016), funding for musculoskeletal conditions from NIH totaled $7.9 billion, while that of cancers and heart/circulatory disorders totaled $42.1 billion and $23.1 billion, respectively. (Reference Table 1.1.1 PDF [17] CSV [18], and Table 1.1.2 PDF [13] CSV [14])

In spite of the major healthcare burden presented by musculoskeletal conditions, research funding falls well below that of most other conditions. Injury research commands half of the musculoskeletal condition research dollars ($4 billion) from NIH for the years 2012 to 2016. Funding for arthritis research is second, at $1.4 billion, followed by osteoporosis ($965 million). These numbers are well below the $8.3 to $55.9 billion in funding for the top 25 NIH research conditions, diseases, and areas. (Reference Table 1.1.3 PDF [21] CSV [22])

Looking at it another way shows the dominance of fatal diseases versus prevalence in the population. Three diseases with very high prevalence in the population – obesity, hypertension, and arthritis – are among the lowest research-funded diseases in the US. Arthritis, a major musculoskeletal disease, is responsible for an extra burden of pain and disability in nearly 1 in 4 persons. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [25] CVS [26])

Since 1999, NIAMS has received an average of 2.8% of research project grant funds, and 2.3% of project grant dollars. Career development awards during this period have risen from 3.1% in 1999 to 4.2% in 2015, as a share of total career awards. (Reference Table 1.1.4 PDF [29] CSV [30])

Time and again, when the global burdens of disease are enumerated, musculoskeletal conditions rank high. Now we see that that rank is increasing. Although research funding reflects a long-term bias towards diseases with high mortality rates, the Global Burden of Disease project indicates that much of the growth in disease burdens has occurred for conditions that cause high disability rates. Redressing the funding disparity should become a high priority.

Although musculoskeletal conditions are common, disabling, and costly, they remain under-recognized, under-appreciated, and under-resourced. This book provides a strong case for the immediate and ongoing need to understand and support musculoskeletal conditions and reduce the burden they bring to people.

In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2015, an annual survey of self-reported health conditions used throughout this chapter to highlight chronic health conditions of the US population, musculoskeletal medical conditions were reported by 124.1 million adults in the United States, representing one in two persons age 18 and over of the estimated 2015 population. The rate of chronic musculoskeletal conditions found in the adult population is greater than that of chronic circulatory conditions, which include coronary and heart conditions, and twice that of all chronic respiratory conditions, the next two most common health conditions. While the rate of circulatory conditions is approaching the rate of musculoskeletal conditions, the majority of circulatory conditions involve high blood pressure and high cholesterol, both of which are controlled medically and do not necessarily lead to the high levels of disability and pain found in arthritis and back pain. (Reference Tables 1.2.1 PDF [32] CSV [33] and 1.3.1 PDF [25] CSV [26])

Females report higher levels of most major non-fatal health conditions than do males. The rate of musculoskeletal conditions in females was 52.7, while males reported musculoskeletal conditions at a rate of 47.3 per 100 persons. (Reference Tables 1.2.1 PDF [32] CSV [33])

Age is a factor in many major health conditions, particularly those affecting the ability to function in daily living activities. The lower prevalence of some conditions in older age groups may be due to mortality caused by the condition in earlier age groups. By age 65, circulatory problems surpass musculoskeletal conditions slightly as hypertension, high cholesterol, and heart conditions all become more common in persons who have reached the age of 75. Respiratory conditions often have lower prevalence among older individuals, while cancer, hearing problems, and dental issues all increase after age 75. The prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions rises in the middle ages of 45 to 64, and tends to level off around age 65, creating a long period of time over which the pain and disability associated with musculoskeletal diseases impacts quality of life. (Reference Table 1.2.2 PDF [36] CSV [37])

Non-Hispanic Whites have the highest prevalence of several major health disease conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions. A major exception to this rule is diabetes, a common condition; prevalence rates of diabetes are highest among non-Hispanic blacks. (Reference Table 1.2.3 PDF [40] CSV [41])

In general, residents of the Midwest region report slightly higher rates of most major health conditions while residents in the West report the lowest prevalence. Musculoskeletal conditions are reported by 54.9% of Midwest residents, and a consistent 48.8% across all other regions. The reasons why this occurs are not known, but the median age of the population is older than the West and South; however, median age is oldest in the Northeast.1 There is also a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions reported in several industries than generally found in other geographical regions. These include construction/extraction, office and administrative support, healthcare practitioners and technicians, and building and grounds cleaning/maintenance industries. (Reference Table 1.2.4 PDF [44] CSV [45])

Over the past decade, the reported prevalence of the most common health diseases has not changed. Reported prevalence in 2012 for several conditions was greater than in 2015, but additional years of data will be needed to determine if this is an actual slowing of these conditions. Circulatory related conditions increased significantly between 20112 and 2015, but this was primarily related to the increase in chronic hypertension, and the addition of chronic high cholesterol to the category. Musculoskeletal diseases continue to lead all medical conditions in prevalence. (Reference Table 1.2.5 PDF [48] CSV [49])

Three of the five most common medical conditions reported in 2012 were musculoskeletal conditions: low back pain, chronic joint pain, and arthritis. The other most commonly reported medical conditions are chronic hypertension and chronic high cholesterol. One in three to four persons over the age of 18 report having these conditions. Back and joint pain, along with arthritis, cause a much higher level of disability and affect quality of life at higher rates than do hypertension and high cholesterol. Major respiratory conditions are reported at much lower rates than circulatory and musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [25] CSV [26])

Females report slightly higher levels of musculoskeletal conditions than do males, but males have higher rates of hypertension and high cholesterol. Age is a factor in increasing prevalence of all major conditions related to musculoskeletal and circulatory diseases, but the rates of hypertension and high cholesterol are much lower in young adults (18 to 44 years) and higher in older age groups (65 and over) than for musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [25] CSV [26]; Table 1.3.2 PDF [53] CSV [54]; Table 1.3.3 PDF [55] CSV [56]; and Table 1.3.4 PDF [57] CSV [58])

Over the last decade, little progress has been made in reducing the prevalence of the most common respiratory, circulatory, and musculoskeletal diseases. In fact, musculoskeletal conditions and chronic hypertension, already affecting a majority of the population, have all seen a slight growth in prevalence. As mentioned earlier, there has been major progress in reducing prevalence of several fatal conditions worldwide. The time has come to focus research on non-fatal diseases, such as musculoskeletal diseases, that can cause many years of pain and disability and have been growing in prevalence. (Reference Table 1.3.5 PDF [59] CSV [60])

As previously noted, musculoskeletal conditions are one of the most debilitating nonfatal health diseases, leading to chronic pain and disability and reduced quality of life. The most common musculoskeletal conditions leading to disability are back and neck pain and arthritis and chronic joint pain.

Back pain affects most people at some point in their lives. For the lucky, this pain has a known cause and is temporary, healing with time and rest. But for many, back pain is a constant in their life. Chronic back pain is considered to be back pain lasting three months or longer. While spinal changes that are the source of back pain may be known and understood, there remains a gap in understanding why some people are affected and others are not, and what can be done to prevent or repair damage done.

In 2015, 72.3 million people age 18 and older reported they experienced chronic back pain in the previous year. This is nearly one in three adults. Of this group, more than one-third (37%) had back pain severe enough that it created radiating leg pain. Two in four (39%) also reported chronic neck pain, but 61% of the 38.9 million with neck pain had chronic neck pain alone.

Females report low back and neck pain at slightly higher rates than males, with females accounting for 54% of low back pain cases, with a rate of 30.8 per 100 persons compared to 27.4 for males. There is an even greater discrepancy in reported neck pain, with females reporting a 33% higher rate per 100 persons than males. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [25] CSV [26])

Low back and neck pain are common among all ages of adults, with reported prevalence leveling as people reach middle age (45 and older). There is an actual slight dip in back pain prevalence in the oldest population, age 75 and older, but back pain remains a significant source of pain and disability throughout people’s lives. (Reference Table 1.3.2 PDF [53] CSV [54])

Low back and neck pain is reported at slightly higher rates among non-Hispanic whites than found in other racial/ethnic populations. Persons of other/mixed non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups report the lowest rates. (Reference Table 1.3.3 PDF [55] CSV [56])

Back pain is reported in similar numbers in all geographic regions, with some minor differences seen. Low back pain is reported at the highest rate (30.3/100) in the Midwest, while low back pain with radiating leg pain is slightly higher in the South (11.3/100). Neck pain is reported highest in the West (17.9/100).

About one in two persons reporting a doctor has “ever” told them they have arthritis report either chronic joint pain or low back/neck pain. It is unknown why some people with arthritis are more likely to report pain than others. More than 55.4 million report they have some type of arthritis, an overall prevalence rate of nearly one in four adults (22.4/100). Females report higher rates than males, accounting for 58% of those reporting they have arthritis. This represents a one-in-four prevalence ratio (25.4/100) compared to one-in-five (19.1/100) males. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [25] CSV [26])

Age is clearly a factor in arthritis, with very low rates found in younger adults. By middle age (45-64) the prevalence rate has more than quadrupled (6.8 to 28.6/100). By the age of 65, the reported prevalence rate has again nearly doubled, to 48.1/100 adults. There is a slight increase again in the oldest population, age 75 and older. (Reference Table 1.3.2 PDF [53] CSV [54])

Persons of non-Hispanic white race/ethnic background report arthritis at a prevalence rate more than twice that of those of Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic other/mixed race/ethnicity. Non-Hispanic blacks report a rate slightly lower than non-Hispanic whites, but still nearly double that of Hispanics and non-Hispanic other/mixed race ethnicity. Understanding why these racial/ethnic differences occur could aid in understanding why some persons get arthritis while others do not, as well as why some persons with arthritis report more pain than others. (Reference Table 1.3.3 PDF [55] CSV [56])

Residents of the Midwest, with a population median age of 38.0 years, report slightly higher rates of arthritis than persons residing in other geographic regions, with residents of the West region, which has the youngest median age (35.9), reporting the lowest rate.1 (Reference Table 1.3.4 PDF [57] CSV [58])

Arthritis is associated with both chronic joint and back pain. Roughly one-half of persons reporting chronic joint pain (54%), low back pain (53%), and radiating leg pain (52%) also report they have arthritis. About one-third (32%) reporting neck pain report they have arthritis.

In recent years, chronic joint pain, defined as joint pain lasting three months or longer, has reached the prevalence level of low back pain as a common musculoskeletal condition. Chronic joint pain, was reported by 72.5 million adults age 18 and older, for a rate of 29.3 in 100 persons. Chronic joint pain and arthritis are not mutually exclusive and may be reported by the same individual. Although age is a general predictor of chronic joint pain and arthritis, with nearly one in two persons age 65 years and older reporting one or both of these conditions, the rate of reported chronic joint pain in younger persons is also of concern. In 2015, one in six persons ages 18 to 44 reported experiencing chronic joint pain in the past year, while more than one-third (37%) age 45 to 64 reported chronic joint pain. Long active lifestyles will continue to be a major cause of joint pain in the coming years. (Reference Table 1.4.1 PDF [65] CSV [66] and Table 1.4.2 PDF [67] CSV [68])

As with other musculoskeletal diseases, chronic joint pain is reported by a slightly higher rate of females than males, as well as among non-Hispanic whites, with one in three reporting chronic joint pain. Other racial/ethnic groups report a prevalence between 20 and 26 in 100 persons with chronic joint pain. Also, the Midwest geographic region reports a higher prevalence than other regions in the US. (Reference Table 1.4.3 PDF [69] CSV [70] and Table 1.4.4 PDF [71] CSV [72])

Chronic knee pain is reported by all ages older than 18 years, with nearly one in three persons age 65 and older reporting chronic knee pain, and one in four (23.9/100) among those 45 to 64 years old. Because only 1 in 10 persons age 18 to 44 reports knee pain, the overall prevalence is 19 in 100. Females report a slightly higher rate of knee pain than males do.

Shoulder pain, reported by 22.3 million of those age 18 and older in 2015, is the second most common joint site for chronic pain, with rates fairly equal for those age 45 and older. Shoulder pain is reported in fairly equal rates by males and females, with males having a slightly higher rate.

Hip pain was reported by 18.2 million people age 18 and older in 2105. Hip pain is much more common in females than in males. As with other sites of chronic joint pain, hip pain prevalence increases with age.

While multiple joints can be the source of chronic joint pain, overall, nearly one in three (29.3/100) people over the age of 18 reported chronic joint pain in 2015. The ratio jumps to nearly one in two (47/100) after the age of 65 years. However, even among younger adults age 18 to 44, about one in six (16.3/100) report chronic joint pain. (Reference Table 1.4.1 PDF [65] CSV [66] and Table 1.4.2 PDF [67] CSV [68])

Over the past eight years, a slight increase in the prevalence rate of reported chronic joint pain has been seen. This is primarily associated with knee pain, but other joints have also seen small increases.

Participants in the NHIS survey are asked about limitations they experience in activities of daily living (ADL) because of medical conditions. In 2015, more than 82 million adults, or 36% of the population age 18 years and older, reported they have difficulty performing routine ADL without assistance because of medical conditions. An additional 6.3 million children between the ages of 1 and 17 years are reported by their parents as needing more assistance in daily activities because of a medical condition than would be expected based on their age. While more than one medical condition could be reported, and often was, 64 million adults with ADL limitations had a musculoskeletal condition, approximately one-half the persons reporting a musculoskeletal condition. This is a much higher ratio than found in any of the other major disease categories.

The prevalence rate in the population reporting limitations in ADL increases with age, and affects one in four persons older than 75 years of age, primarily due to musculoskeletal conditions. Again, females, non-Hispanic whites, and residents of the Midwest are slightly more likely to report limitations due to health conditions than other demographic groups (Reference Tables 1.5.1 PDF [11] CSV [12]; 1.5.2 PDF [81] CSV; [82] 1.5.3 PDF [83] CSV [84]; and 1.5.4 PDF [85] CSV [86])

Spine problems with the back and neck are the most common musculoskeletal condition to cause limitations in ADL in young adults, but as the population ages, arthritis or rheumatism is a more common cause. The mean duration for limitations reported for all musculoskeletal conditions is 8 to 18 years. Although there is an increase in years of duration as the population ages, even among young adults aged 18 to 44, the duration of musculoskeletal conditions causing limitations is 8 years or more. (Reference Table 1.6.2 PDF [89] CSV [90])

Reflecting the overall prevalence of medical conditions in females, they are also more likely to report impairment in ADL than are males. This is particularly true for musculoskeletal conditions. Females account for 58% of all persons reporting they are limited in activities of daily living; they account for 59% of those reporting a musculoskeletal condition impairment. Two of three adults age 18 and older (64%) reporting arthritis as a cause for ADL limitations are female, while 59% of those reporting connective tissue problems, including fibromyalgia, as the cause of ADL limitations are female. (Reference Tables 1.5.1 PDF [11] CSV [12] and 1.6.1 PDF [93] CSV [94])

Non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, overall, report higher rates of limitation due to medical conditions than Hispanics and non-Hispanic other/mixed race/ethnic persons, except for limitations due to circulatory diseases. Limitations due to musculoskeletal conditions are all reported at higher rates by non-Hispanic whites than by other racial/ethnic groups. (Reference Tables 1.5.3 PDF [83] CSV [84] and 1.6.3 PDF [95] CSV [96])

Again, residents of the Midwest report slightly higher rates of limitations due to medical conditions for all musculoskeletal diseases than do residents of other geographic regions in the US. (Reference Table 1.6.4 PDF [97] CSV [98])

Activities of daily living include walking, climbing steps, standing or sitting for extended periods of time, stooping, reaching, grasping, carrying or pushing/pulling large objects, shopping, and social activities or just relaxing. The number of adults with most major health conditions who have difficulty performing these activities is quite low, representing fewer than two or three adults out of 100. The exception is adults reporting musculoskeletal conditions, for whom the overall rate for a limitation in the performance of any ADL is nearly 15 in 100 persons. For individual ADL, those with musculoskeletal conditions report limitations at two to six times the rate found for other major health conditions. (Reference Table 1.7.1 PDF [99] CSV [100])

Among the adult population in the work force, 38 in 1000 report they are unable to work at all due to a musculoskeletal disease, with an additional 21 reporting they can do only limited work. This is two times or greater than the rate of the second most work limiting condition, circulatory diseases. (Reference Table 1.7.2 PDF [103] CSV [104])

Respondents to the 2015 NHIS self-reported the number of bed days and lost work days they experienced in the previous 12 months due to a variety of medical conditions. A bed day is defined as one-half or more days in bed because of injury or illness in past 12 months, excluding hospitalization. A missed, or lost, work day is defined as absence from work because of illness or injury in the past 12 months, excluding maternity or family leave.

Although the exact cause of these bed and lost work days cannot be determined because some respondents reported multiple health conditions, 70% of persons reporting bed and lost work days reported having a musculoskeletal condition. This is more than twice the proportion of respondents reporting depression, the second most common medical condition listed for causing lost work days, and five or more times the proportion pf respondents reporting other major health conditions. Overall, the high proportion of workers reporting lost work days or bed days as a result of a musculoskeletal condition results in an economic burden on the economy—much higher than that reported for chronic circulatory or chronic respiratory conditions. (Reference Table 1.8.1 PDF [107] CSV [108] and Table 1.8.2 PDF [109] CSV [110])

More than one in four adults in the population (27%), a total of 54 million, reported at least one bed day in the previous 12 months because of a medical condition. More than one-half (14.7%) reported having a musculoskeletal condition, more than reported any other condition. Respondents could report multiple conditions, and bed days could be associated with more than one condition. The mean number of bed days reported with musculoskeletal conditions was 20.4, for a total of 1.1 billion bed days. While other conditions were likely the cause of a higher mean number of bed days, the share of the population reporting these conditions was much smaller.

Males and females reported a similar mean number of bed days due to musculoskeletal conditions (20 days vs 21 days), however, because more females report musculoskeletal conditions and bed days than males, the total bed days attributed to females is much greater. Adults in their middle years, age 45 to 64, report higher rates of bed days because of musculoskeletal conditions than do adults age 18 to 44 or over 65.

More than 35 million adults in the workforce with a musculoskeletal condition reported lost work days in the previous 12 months, totaling nearly 364 million days. Lost work days for persons with a musculoskeletal conditions accounted for more lost work days than any other major health condition, with workers losing an average of 10 days of work. Chronic circulatory conditions, including high blood pressure and heart conditions, accounted for 283 million lost work days, and were reported by an increasing share of the working age population.

As with bed days, females and males reported similar numbers of lost work days, but again, the number of females was higher. The youngest members of the work force, those age 18 to 44, accounted for the largest number of workers with lost work days due to a musculoskeletal condition, but they also represent the largest share of the work force population. They reported a mean of three fewer days lost than the older 45 to 64 worker population. The oldest workers, those age 65 and over, reported a mean of nearly 14 days lost, but comprised a very small share of the work force.

Musculoskeletal diagnoses accounted for 19.2%, or 235.1 million, of the 1.225 billion medical diagnoses included in hospital discharge records, emergency department and outpatient clinic visits, and physician office visits in the United States in 2013. Seven in ten of the discharges/visits were to a physician’s office, but musculoskeletal visits as a share of total healthcare visits were highest for hospital discharges (29.6%) and emergency department visits (28.9%). (Reference Table 1.9.1 PDF [119] CSV [120] and Table 1.9.2 PDF [121] CSV [122])

On average, each person in the United States received medical care for four diagnoses during 2013, or 3,874 diagnoses per a population of 1,000. Of these, 747 diagnoses were for musculoskeletal conditions, indicating that seven in ten persons had a healthcare discharge or visit related to a musculoskeletal disease. The most common musculoskeletal diagnoses are "other and unspecified disorders of the back" and "other and unspecified disorders of joints," with 141.9 and 106.8 diagnoses per 1,000 persons, respectively. Of the more specific diagnoses, disc disorders (50.4/1000), osteoarthrosis and allied disorders (49.6/1000) spondylosis and allied disorders (22.2/1000) were the most common. (Reference Table 1.9.3 PDF [125] CSV [126])

The majority of all diagnoses and musculoskeletal diagnoses are made in a physician office. However, hospital discharges and emergency department visits are seen more frequently for musculoskeletal conditions than for health care visits for all conditions overall. (Reference Table 1.9.2 PDF [121] CSV [122])

Among the major diagnostic categories of musculoskeletal diagnoses, Arthritis and Other Rheumatic Conditions (AORC) accounted for nearly half the musculoskeletal related visits at a rate of 350.8/1000. Spine and injuries each accounted for just over one in five visits (210.1/1000 and 207.7/1000, respectively). Although the remaining musculoskeletal disease diagnostic categories represent much smaller shares of visits and impact fewer persons, they remain a major cause for pain and disability. (Reference Table 1.9.6 PDF [129] CSV [130])

Musculoskeletal procedures comprised only slightly more than 1% of all medical procedures performed in hospitals, outpatient clinics, emergency departments, and physician offices in 2013. However, 62 musculoskeletal procedures were performed more than 12,000 times each. The top two procedures, together performed nearly 5.8 million times, are the injection of a therapeutic substance into a joint or ligament and into soft tissue. The third most frequently performed musculoskeletal procedure, performed nearly 800,000 times in 2013, was arthrocentesis, the removal of fluid from a joint. All three are routinely performed in a physician’s office. Joint replacement procedures ranked 4th (total knee), 7th (total hip), 16th (partial hip), and 19th (revision knee replacement), all of which are projected to increase dramatically by 2030, particularly by persons under the age of 65.1 Reduction of fractures and spinal fusion procedures rounded out the remaining top 20 procedures. These procedures are primarily performed in a hospital. (Reference Table 1.10.1 PDF [133] CSV [134])

Looking at musculoskeletal procedures by major groups (2-digit ICD-9-CM codes), 60% of procedures belong to the repair and plastic operations on joint structures (81). This group includes joint replacement and spinal fusion procedures, both among the most frequent procedures performed, as well as injections of therapeutic substance into joint or ligament, the most frequent musculoskeletal procedure performed. Operations on muscle, tendon, fascia, and bursa comprise 10% of all musculoskeletal procedures performed. This category (83) includes the second most frequent procedure, injection of locally-acting therapeutic substance into other soft tissue. (Reference Table 1.10.2 PDF [135] CSV [136])

The annual average proportion of the US population with a musculoskeletal condition requiring medical care has increased by more than six percentage points over the past two decades and now constitutes more than 34% of the population. This is an overall rate of increase of 21%. The majority of growth in both the proportion of the population, and in the number of people with a musculoskeletal condition is in the 45 to 64-year age bracket, with persons age 65 years and older with musculoskeletal conditions also rising. (Reference Table 8.1.1 PDF [139] CSV [140])

In 2012 to 2014, the annual estimated direct and indirect cost attributable to persons with a musculoskeletal disease is $322 billion. Taking into account all costs for persons with a musculoskeletal disease including other co-morbid conditions, the cost of treating these individuals and the cost to society in the form of decreased wages is estimated to be nearly $980 billion per year. Over the last 18 years, costs associated with musculoskeletal conditions have risen from 3.44% of the GDP to 5.76%. (Reference Table 8.6.1 PDF [143] CSV [144]; Table 8.12 PDF [145] CSV [146]; and Table 8.14 PDF [147] CSV [148])

Treatments that mitigate the long-term impacts of musculoskeletal conditions and return persons to full and active lives are needed.

The increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions, along with a growing and aging population, has resulted in more than a 44% increase in total aggregate direct cost to treat persons with a musculoskeletal condition over the past decade (2002-2004 to 2012-2014), in constant 2014 dollars. For the years between 2012 and 2014, the annual average direct cost in 2014 dollars for musculoskeletal health care—both as a direct result of a musculoskeletal disease and for patients with a musculoskeletal disease in addition to other health issues—is estimated to be $980.1 billion, the equivalent of 5.76% of the national gross domestic product (GDP).

Total medical care costs are the costs for treating all of an individual’s conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions. Incremental medical care costs are that part of total medical care costs attributable solely to the musculoskeletal conditions. Incremental medical costs for musculoskeletal conditions for the years between 2012 and 2014 are estimated to be $162.4 billion, in 2014 dollars. (Reference Table 8.14 PDF [147] CSV [148], and Table 8.6.1 PDF [143] CSV [144])

Indirect costs measure disease impact in terms of lost wages due to disability or death. Indirect costs, like medical care costs, can be estimated and calculated in total for all the medical conditions an individual has, and as the increment attributable solely to musculoskeletal conditions.

Indirect cost for people age 18 to 64 with a work history add another $97.5 billion, or 0.5% of the GDP in between 2012 and 2014, to the cost for all persons with a musculoskeletal disease, either treated as a primary condition or in addition to another condition. Annual indirect costs attributable to musculoskeletal disease alone (incremental cost) account for an estimated $159.2 billion. Indirect costs attributable to musculoskeletal disease are greater than total indirect costs wage losses attributable to musculoskeletal conditions are greater than the mean difference in wages between the two groups, an indication that persons with musculoskeletal conditions work less than expected of persons their ages. (Reference Table 8.12 PDF [145] CSV [146])

The importance of musculoskeletal conditions in society necessarily increases with an aging population since the prevalence and impact increase with age. An aging population puts increased numbers of persons in the age range of greatest risk for onset and worsened severity. However, it is not only among the elderly, or persons age 65 or older, that the impacts of aging are felt. Because the prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions is substantial among those 45 to 64 years of age, the proportion of all cases of musculoskeletal disease in this age range increased by one-third over a 15-year time frame, from about 29% (21.8 million persons) in the years 1996 to 1998 to about 38% (40.7 million persons) between 2012 and 2014. During the same time periods, the proportion of cases among the elderly increased by 19%, from about 22% (16.5 million persons) in the earlier three-year period to about 26% (27.8 million persons) in the later one. (Reference Table 8.1.1 PDF CSV) Because conditions that exist among persons age 45 to 64 are likely to last for a long time, the increased proportion of cases in this age range may lead to protracted high medical care costs in the years to come.

The relative importance of this age range in costs of care is already clear. Between 1996 to 1998 and 2012 to 2014, the proportion of all medical care costs experienced by persons with musculoskeletal conditions who are between ages 45 and 64 increased by 39%, from about 30% of all such costs to 42%. The proportion of incremental musculoskeletal medical care costs among persons 45 to 64 years of age increased by an even more, 82%, rising from 28% in the 1996 to 1998 period to 51% between 2012 and 2014. (Reference Table 8.9 PDF [151] CSV [152])

The aging of the US population puts an increased proportion of the population at the ages of highest risk of the onset of musculoskeletal conditions and, among those with these conditions, at the ages of highest severity levels. The problem of aging is made more severe by the fact that many major chronic diseases are more prevalent in late middle age and among the elderly. In fact, most of the latter group has two or more chronic diseases. The impact of comorbidity is reflected in the cost data presented in this volume. Not only are the incremental costs, that is, those attributable to the musculoskeletal conditions, high among those age 45 and older, but the total medical costs they experience are also higher in these age ranges. The problems of an aging population are exacerbated by the occurrence of multiple chronic diseases.

The increased prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions associated with the aging population will necessarily place increased demands on the healthcare system. However, the growth in the healthcare workforce is not keeping pace with the growing prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions. In fact, two medical specialties focused on the care of persons with these diseases, rheumatology and geriatrics, are having a difficult time recruiting new physicians.

It is also the case, as documented in The Big Picture: Funding [153]that research funding for musculoskeletal conditions, relatively small to begin with, is not keeping up with the growing importance of this disease group. Prior research has led to dramatically improved treatments for inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (principally because of the development of biological treatments) and to mechanical ones such as osteoarthritis (principally because of the improvement in total joint replacement rates). However, in order to deal with the increased numbers of patients associated with the aging population, research funding must be expanded in sheer dollars and in scope to encompass the cause, treatment, and organization of care.

The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS) project was designed to provide primary data on musculoskeletal disorders related to prevalence and incidence, healthcare utilization, and burden, including economic costs, in the US as tools to support policy decision makers in the need for greater attention to be paid to musculoskeletal diseases. As BMUS moves forward, it is being asked to include a much broader picture of musculoskeletal disorders, including, but not limited to, a better description and understanding of disorders, comparison to global burden, treatment options/effectiveness/costs, quality of life, disparities in diagnosis and treatment, and the role of comorbidities. All these areas are critical to addressing the importance of recognizing and treating musculoskeletal diseases. Data to support addressing these issues must be addressed.

More than one in two persons age 18 years and older in the US population reports a chronic musculoskeletal condition. This compares to a rate of 42 and 24 persons per every 100 in the population for circulatory (including treatment for high blood pressure) and respiratory conditions, respectively.

Chronic low back pain, joint pain, and disability from arthritis comprise three of the top five most commonly reported medical conditions. The two non-musculoskeletal conditions are chronic hypertension and chronic high cholesterol. All five conditions were reported by 55 million or more persons in 2015. This compares to less than 30 million with other common conditions such as coronary or respiratory conditions. The number of persons suffering from musculoskeletal conditions is expected to continue to increase as once active individuals move into their older years.

The cost to treat the pain and disability resulting from musculoskeletal diseases is rising rapidly. The annual average direct and indirect (because of lost work) costs attributable to persons with a musculoskeletal disease were $322 billion between 2012 and 2014. Over the last 18 years, costs associated with musculoskeletal conditions have risen from 3.44% of the GDP to 5.76%.

In spite of this, research funding for musculoskeletal-related conditions remains substantially below that of other major health conditions, such as cancer and respiratory and circulatory diseases. If healthcare costs in the future are to be contained, musculoskeletal diseases must come to the forefront of medical research efforts.

135 : Sarcoidosis

170 : Malignant neoplasm of bone and articular cartilage

171 : Malignant neoplasm of connective and other soft tissue

198 : Secondary malignant neoplasm of bone and bone marrow

203 : Multiple myeloma and immunoproliferative neoplasms

213 : Benign neoplasm of bone and articular cartilage

215 : Other benign neoplasm of connective and other soft tissue

238 : Neoplasm of uncertain behavior of other and unspecified sites and tissues; Connective and other soft tissue; Bone soft tissue and skin

239.2 : Neoplasms of unspecified nature; Bone soft tissue and skin

274 : Gout; Gouty arthroplathy

710 : Diffuse diseases of connective tissue

711 : Arthropathy associated with infections

712 : Crystal arthropathies

713 : Arthropathy associated with other disorders classified elsewhere

714 : Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies

715 : Osteoarthrosis and allied disorders

716 : Other and unspecified arthroplasties

717 : Internal derangement of knee

718 : Other derangement of joint

719 : Other and unspecified disorders of joint

720 : Ankylosing spondylitis and other inflammatory spondylopathies

721 : Spondylosis and allied disorders

722 : Intervertebral disc disorders

723 : Other disorder of cervical region

724 : Other and unspecified disorders of back

725 : Polymyalgia rheumatica

726 : Peripheral enthesopathies and allied syndromes

727 : Synovitis and tenosynovitis

728 : Disorders of muscle, ligament, and fascia

729 : Other disorders of soft tissue

730 : Acute osteomyelitis

731 : Osteitis deformans and osteopathies associated with other disorders classified elsewhere

732 : Osteochondropathies

733 : Other disorders of bone and cartilage (Osteoporosis; pathologic fracture, cyst, necrosis of bone, malunion and nonunion of fracture)

734 : Flat foot

735 : Acquired deformities of toe

736 : Acquired deformities of forearm

737 : Curvature of spine

738 : Other acquired deformity (of musculoskeletal system), spondylolisthesis

739 : Nonallopathic lesions, not elsewhere classified

741 : Spina bifida

754 : Certain congenital musculoskeletal deformities

755 : Other congenital anomalies of limbs (Polydactyly)

756 : Other congenital musculoskeletal anomalies

805 : Fracture of vertebral column without mention of spinal cord injury

806 : Fracture of vertebral column with mention of spinal cord injury

807 : Fracture of vertebral column with mention of spinal cord injury

808 : Fracture of pelvis (Acetabulum, closed)

809 : Ill-defined fractures of bones and trunk

810 : Fracture of clavicle (closed)

811 : Fracture of scapula (closed)

812 : Fracture of humerus (Upper end, closed)

813 : Fracture of radius and ulna (Upper end, closed)

814 : Fracture of carpal bone(s) (Closed)

815 : Fracture of metacarpal bone(s) (Closed)

816 : Fracture of one or more phalanges of hand (Closed)

817 : Multiple fractures of hand bones

818 : Ill-defined fractures of upper limb

819 : Multiple fractures involving both upper limbs, and upper limb with rib(s) and sternum

820 : Fracture of neck of femur (transcervical fracture, closed)

821 : Fracture of other and unspecified parts of femur (Shaft or unspecified part, closed)

822 : Fracture of patella

823 : Fracture of tibia and fibula, upper end (closed)

824 : Fracture of ankle

825 : Fracture of one or more tarsal and metatarsal bones

826 : Fracture of one or more phalanges of foot

827 : Other, multiple, and ill-defined fractures of lower limb

829 : Fractures of unspecified bones

831 : Dislocation of shoulder

832 : Dislocation of elbow

833 : Dislocation of wrist

834 : Dislocation of finger

835 : Dislocation of hip

836 : Dislocation of knee

837 : Dislocation of ankle

838 : Dislocation of foot

839 : Other, multiple, and ill-defined dislocations

840 : Sprains and strains of shoulder and upper arm

841 : Sprains and strains of elbow and forearm

842 : Sprains and strains of wrist and hand

843 : Sprains and strains of hip and thigh

844 : Sprains and strains of knee and leg

845 : Sprains and strains of ankle and foot

846 : Sprains and strains of sacroiliac region

847 : Sprains and strains of other and unspecified parts of back

848 : Other and ill-defined sprains and strains

875 : Open wound of chest (wall)

876 : Open wound of back

877 : Open wound of buttock

879 : Open wound of other and unspecified sites (except limbs)

880 : Open wound of shoulder and upper arm

881 : Open wound of elbow, forearm, and wrist

882 : Open wound of hand except finger(s) alone

883 : Open wound of finger(s)

884 : Multiple and unspecified open wound of upper limb

885 : Traumatic amputation of thumb

886 : Traumatic amputation of other finger(s)

887 : Traumatic amputation of arm and hand (complete) (partial)

890 : Open wound of hip and thigh

891 : Open wound of knee, leg [except thigh], and ankle

892 : Open wound of foot except toe(s) alone

893 : Open wound of toe(s)

894 : Multiple and unspecified open wound of lower limb

895 : Traumatic amputation of toe(s)

896 : Traumatic amputation of foot (complete) (partial)

897 : Traumatic amputation of leg(s) (complete) (partial)

922 : Contusion of trunk

923 : Contusion of upper limb

924 : Contusion of lower limb and of other and unspecified sites

926 : Crushing injury of trunk

927 : Crushing injury of upper limb

928 : Crushing injury of lower limb

929 : Crushing injury of multiple and unspecified sites

954 : Injury to other nerve(s) of trunk, excluding shoulder and pelvic girdles

955 : Injury to peripheral nerve(s) of shoulder girdle and upper limb

956 : Injury to peripheral nerve(s) of pelvic girdle and lower limb

959 : Injury, other and unspecified (to musculoskeletal system)

996 : Complications peculiar to certain specified procedures

V43.6 : Organ or tissue replaced by other means (joint)

V54 : Other orthopaedic aftercare

V67 : Follow-up examination, following surgery

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4leading-causes-yldspng

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_Leading%20causes%20of%20YLDs.png

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g101png

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.0.1.png

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g102png

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.0.2.png

[7] http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2016/cb16-54.html

[8] https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html

[9] http://www.healthdata.org/research-article/global-regional-and-national-incidence-prevalence-and-years-lived-disability-2013

[10] http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/downloadablefiles.html

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.1.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.1.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.2.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.2.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1a1png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.A.1.png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.1.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.1.csv

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1a2png

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.A.2.png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.3.pdf

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.3.csv

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1a3png

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.A.3.png

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.1.pdf

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.1.csv

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1a4png

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.A.4.png

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.4.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.1.4.csv

[31] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45354/

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.1.pdf

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.1.csv

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b01png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.1.png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.2.pdf

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.2.csv

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b02png

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.2.png

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.3.pdf

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.3.csv

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b03png

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.3.png

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.4.pdf

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.4.csv

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b04png

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.4.png

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.5.pdf

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.5.csv

[50] https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b11png

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.1.1.png

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.2.pdf

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.2.csv

[55] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.3.pdf

[56] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.3.csv

[57] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.4.pdf

[58] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.4.csv

[59] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.5.pdf

[60] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.5.csv

[61] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b21png

[62] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.1.png

[63] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b22png

[64] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.2.png

[65] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.1.pdf

[66] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.1.csv

[67] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.2.pdf

[68] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.2.csv

[69] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.3.pdf

[70] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.3.csv

[71] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.4.pdf

[72] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.4.csv

[73] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b23png

[74] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.3.png

[75] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b24png

[76] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.4.png

[77] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b24tpng

[78] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.4t.png

[79] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1c01png

[80] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.C.0.1.png

[81] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.2.pdf

[82] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.2.csv

[83] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.3.pdf

[84] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.3.csv

[85] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.4.pdf

[86] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.5.4.csv

[87] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1c02png

[88] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.C.0.2.png

[89] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.2.pdf

[90] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.2.csv

[91] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1c03png

[92] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.C.0.3.png

[93] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.1.pdf

[94] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.1.csv

[95] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.3.pdf

[96] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.3.csv

[97] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.4.pdf

[98] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.6.4.csv

[99] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.7.1.pdf

[100] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.7.1.csv

[101] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1c11png

[102] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.C.1.1.png

[103] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.7.2.pdf

[104] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.7.2.csv

[105] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1c12png

[106] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.C.1.2.png

[107] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.8.1.pdf

[108] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.8.1.csv

[109] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.8.2.pdf

[110] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.8.2.csv

[111] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1d11png

[112] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.D.1.1.png

[113] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1d12png

[114] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.D.1.2.png

[115] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1d21png

[116] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.D.2.1.png

[117] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1d22png

[118] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.D.2.2.png

[119] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.1.pdf

[120] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.1.csv

[121] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.2.pdf

[122] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.2.csv

[123] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1e01png

[124] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.E.0.1.png

[125] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.3.pdf

[126] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.3.csv

[127] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1e02png

[128] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.E.0.2.png

[129] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.6.pdf

[130] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.9.6.csv

[131] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1e03png

[132] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.E.0.3.png

[133] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.10.1.pdf

[134] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.10.1.csv

[135] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.10.2.pdf

[136] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.10.2.csv

[137] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1e11png

[138] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.E.1.1.png

[139] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.1.pdf

[140] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.1.1.csv

[141] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1f01png

[142] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.F.0.1.png

[143] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.1.pdf

[144] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.6.1.csv

[145] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.12.pdf

[146] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.12.csv

[147] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.14.pdf

[148] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.14.csv

[149] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1f02png

[150] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.F.0.2.png

[151] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.9.pdf

[152] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T8.9.csv

[153] http://www.boneandjointburden.org/fourth-edition/ia0/funding