[6]

[6]

The burden of musculoskeletal issues on the military population cannot be overstated. Further, the impact of these injuries does not stop when the service member transitions out of the military. Musculoskeletal injuries and conditions are one of the greatest threats to our military’s readiness and troops ability to deploy and as such, bear a substantial significance for our society as a whole.1,2 Further, inability to return to full duty due to musculoskeletal injury or pre-existing musculoskeletal condition is the most common reason for medical discharge from the Armed Services across all branches,3,4 with almost 78% of male Army personnel and 85% of females with a disability discharge discharged due to a musculoskeletal injury or condition.4 There is anecdotal and some scientific evidence on medical discharges from the British armed forces that females in military service experience an excess of work-related injuries, compared with males.5

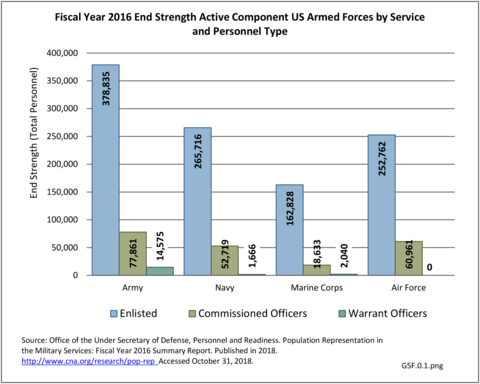

During Fiscal Year 2016, there were nearly 1.3 million active duty service members (enlisted plus officers) and an additional 860,000 Reserve and National Guard members. Among all branches of the Department of Defense enlisted personnel (1.06 million), 84% are male and 16% female. Female personnel were slightly younger, with 86% under the age of 35, compared to 83% of male personnel under 35 years of age. This is nearly double the percentage of the civilian population under age 35, years where in both male and female persons only 44% is under 35 years of age. The Marine Corps has the highest proportion of personnel under the age of 35 years, with 92.5% of the enlisted component of the Marine Corps less than 35 years. The young age and high activity level of the active duty military population brings about a unique set of musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 5F.0.1 PDF [1] CSV [2] and Table 5F.0.2 PDF [3] CSV [4]) (G5F.0.1, G5F.0.2, G5F.0.3)

The military summary data presented here is largely derived from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) from the Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) annual reports on non-deployed, Active Duty United States military personnel. The DMSS examines total numbers of hospitalizations and ambulatory visits broken down by a defined set of diagnostic categories based on ICD-9-CM, and in the most recent years the ICD-10-CM, codes. In general, musculoskeletal injuries and conditions are compiled into two major diagnostic classifications, “injury and poisoning” or “musculoskeletal system” conditions. Typically, diagnoses included in the “injury and poisoning” category are more acute in nature (i.e. fractures, ligament tears, shoulder dislocations, etc.), while more chronic conditions (i.e. osteoarthritis, tendinitis, stress fractures, etc.) are included in the “musculoskeletal system” category.

Excluding pregnancy-related visits, ”injury and poisoning” and “musculoskeletal system” are consistently amongst the top causes for hospitalization and consistently ranked second and fourth most frequent diagnoses across all military personnel. Mental disorders and digestive systems are commonly ranked first and third. This illustrates the significant overall burden of musculoskeletal problems in relation to all other medical conditions treated at Military Treatment Facilities (MTFs). (Reference Table 5F.1.1.1 PDF [13] CSV [14])

Broken down by service branch, the rate of hospitalization per person-year for all diagnostic categories is higher for Army personnel than for other service branches. Since the Army has more than double the number of personnel in other branches, the absolute number of hospitalizations is much higher and therefore not a valid comparison point. (Reference Table 5F.1.1.2 PDF [17] CSV [18])

The total morbidity burden (hospitalizations plus ambulatory visits) for injury/poisoning events ranks as the number one cause of medical treatment received at MTFs. More than 540,000 service members were treated annually for an injury/poisoning event each year from 2012 to 2017. This accounted for roughly 25% of all encounters at military hospitals over that time frame. Additionally, injury/poisoning events resulted in 12% of hospital bed days and ultimately almost 25% of lost work time. (Reference Table 5F.1.1.3 PDF [21] CSV [22])

Musculoskeletal injuries in the military encompass a wide range of pathology from chronic overuse conditions to acute injuries from training accidents to high energy blast injuries sustained on deployments. Given the overall young age of military cohorts, injuries sustained are often sports or training related and not unlike what would be seen in a civilian Sports Medicine practice; however, these injuries often occur at a higher incidence when compared with their civilian counterparts. The high energy blast injuries that we grew accustomed to during the heights of the Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) conflicts have decreased over the last decade yet still remain a significant cause for morbidity and mortality amongst the military population.1

In 2012, battle injuries comprised 7% of hospitalization due to injury but fell to 1% or less in subsequent years. The overall rate of hospitalization for injuries/poisoning events has fallen over the last five years from 7.7 per 1,000 person-years in 2012 to 5.0 per 1,000 person-years in 2017. The most common cause of hospitalized injuries reported was falls. In recent years, however, the cause of more than half of hospitalizations due to injury was not identified, which makes a direct comparison challenging. (Reference Table 5F.1.2.1 PDF [25] CSV [26])

The rate of hospitalization for injuries per person-year is consistently highest in the Army and lowest in the Air Force. Based on the 2016 distribution of Armed Forces by sex (84% male; 16% female), females are slightly less likely to be hospitalized for an injury/poisoning event across all branches. (Reference Table 5F.1.2.2 PDF [29] CSV [30] and Table 5F.1.2.3 PDF [31] CSV [32])

The most common reason for ambulatory visits within the military has consistently been the “musculoskeletal system,” and the rate per person year has steadily increased over the 2012 to 2017 time period. Additionally, injury and poisonings are the 5th most common cause of ambulatory healthcare visits in the US Armed Forces, which also increased over the time period between 2012 and 2017. While the absolute number of visits is impacted by the annual end strength of the Armed Forces, the rate of ambulatory visits has not changed considerably between 2012 and 2017 despite fluctuations in total number of personnel. Overall, more than half the active component of the Armed Forces personnel had an ambulatory visit for an injury event each year resulting in an annual per person rate of 0.6-0.7, or roughly two in three personnel.

The direct care system (DCS) includes military treatment facilities (MTF) comprised of medical centers, hospitals, and clinics found at military bases and posts in the US and around the world dedicated to providing healthcare to DoD-eligible beneficiaries and staffed and run by DoD personnel. In addition, the military health system (MHS) provides purchased care contracted outside of an MTF that provides or supplements care to beneficiaries that is either unavailable in the DCS or falls outside the MTF market area.

For personnel treated at a MTF, disposition (ie, full, light or limited duty) of patients are tracked closely. In 2017, the illness-and injury-related diagnostic categories with the highest proportions of “limited-duty” dispositions were injuries and poisonings (17.5%) and musculoskeletal disorders (13%).1 However, treatment visits in purchased care facilities are not always identified. (Reference Table 5F.1.3.1 PDF [35] CSV [36] and Table 5F.1.3.3 PDF [37] CSV [38])

Unlike hospitalizations for injury/poisoning events, where females are slightly less likely to be hospitalized, they are slightly more likely to have an ambulatory visit. (Reference Table 5F.1.3.2 PDF [41] CSV [42])

The diagnostic cause of ambulatory visits for injury/poisoning events is also provided in the MSMR Annual Summary Edition. While the proportion of visits varies somewhat by year and by sex, injury causes are consistent overall with the top two injuries being ankle sprains and sprains of the cruciate ligament of the knee. Between 8% and 10% of all ambulatory injuries are a sprain of the ankle, with foot injuries sometimes included in this diagnosis category depending on coding. Sprains of the cruciate ligament (knee) is the second most common, accounting for 3% to 4% of injuries. Sprains and strains of the shoulder and upper arm are more common among males, while females are more often diagnosed with sprain of the hip. (Reference Table 5F.1.3.4 PDF [43] CSV [44])

Routine, repetitive physical training and job requirements place service members at risk for common overuse conditions throughout the body. Prolonged overhead activities combined with routine physical training involving push-ups and pull-ups place this population at risk of developing common chronic conditions of the upper extremity. Some of the most common conditions include shoulder impingement, rotator cuff tendinopathy, medial and lateral epicondylitis, and degenerative wrist conditions like scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) and scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC). Patellofemoral syndrome, patellar tendinitis, and iliotibial band syndrome are among the common overuse injuries affecting the knee in activity duty military populations. Ankle sprains leading to chronic ankle instability are also a common cause of disability in this cohort and occur at a rate 5-6 times higher than in the general population.2 Finally, chronic back and neck issues are a significant cause of morbidity and can ultimately result in the inability of the patient to perform the duties required of them to remain on Active Duty.

Stress fractures have long been a subject of interest in the military population given the treatment cost and significant time lost to injury this condition has. A recent epidemiological study found 31,758 lower extremity stress fractures occurred over a three-year time period, with 40% occurring in the tibia/fibula, 16% in the metatarsals, 9% in the femoral neck, 6% in the femoral shaft, and 30% in other unspecified bones.3 Females had a significantly increased risk of suffering from a stress fracture in any bone compared to their male counterparts; nearly 3-fold in this study. This gender difference has been repeatedly demonstrated and is attributed to anatomic, physiologic, and endocrinologic differences between males and females.4,5,6 Given the significant burden this condition has on troop readiness, identifying those at risk for stress fractures and improving prevention strategies should be a primary research focus going forward.

Acute injuries in the Active Duty population occur most commonly as a result of training accidents or sporting injuries. Causes of injury hospitalizations are coded according to the coding scheme outlined in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Standardization Agreement (STANAG) No. 2050, ed. 5.7

Falls and land transport consistently rank as the top unintentional causes for injury hospitalizations. Among all medical encounters for injuries and poisoning events (both hospitalization and ambulatory), musculoskeletal injuries to the knee, arm and shoulder, and foot and ankle all consistently rank in the top 10 out of 142 disease conditions. This is true both in total number of encounters and individuals affected, comprising at least two-thirds of medical encounters and more than one-half of individuals affected attributable to injuries and poisoning. (Reference Table 5F.1.4.1 PDF [45] CSV [46] and Table 5F.1.4.2 PDF [47] CSV [48])

Among the most common acute injuries managed in the military population are fractures, ligamentous or meniscal knee injuries, and shoulder dislocations. Fractures can occur anywhere in the body but most often are seen in the hand and wrist (metacarpals, scaphoid, distal radius), ankle, and clavicle in the active duty population, and occur at a higher incidence than their civilian counterparts.8,9,10 These fractures often require operative fixation resulting in significant lost duty time and an increased likelihood that the patient is unable to return to full duty.

Multiple studies have shown an almost 10-fold higher incidence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscal injuries in active duty service members compared to the general population.11,12,13 In contrast to injury patterns seen in civilians, men were at increased risks of sustaining these injuries compared to females; this may be attributable to differences in occupational tasks and activities between men and women in the military.

Shoulder dislocations and resultant shoulder instability are ubiquitous in the Active Duty population; a 7 to 21 times higher incidence of shoulder dislocation injury has been reported compared to the general population.14,15 These injuries often require surgical repair in this population with approximately 9% of those who require surgery being discharged for disability due to their injury.16

Identifying those at risk of sustaining these debilitating injuries and implementing preventive strategies should be of utmost importance in attempting to curb the resultant costly disability to our military members.

The true cost of military injuries is difficult to define due to the complexity of injuries and the long-lasting implications on the service member. In addition to actual treatment costs of the index injuries, we must take into account the added financial burden associated with time away from duty, long-term care for severely injured, and the effects of war trauma. In recent years (2012 to 2017), injuries and poisoning events cost a morbidity burden of 40,000 to 68,000 bed days among active category Armed Forces personnel. (Reference Table 5F.1.4.3 PDF [51] CSV [52])

The Army has estimated the cost of Basic Combat Training (BCT) injuries to be $22 million annually for treatment of the 40% of men and 61% of women who sustain BCT-related injuries annually. The most common types of injuries were sprains, strains, joint pain, and back pain.1

Injury costs associated with the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan will be staggering for decades to come. One out of every two veterans from these two conflicts has already applied for permanent disability benefits. Higher survival rates for amputees and other catastrophic injuries that require life-long care further add to the economic burden of these disability costs associated with musculoskeletal injuries. The present value of the expected total medical care for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans already committed to be delivered over the next forty years is projected to be $288 billion.2

The impact of musculoskeletal injuries on the service member does not stop when they leave the military. Degenerative conditions have been shown to plague the aging military population. Fragility fractures are less common in the active duty population, but certainly have a profound effect on the Veteran community. The years of consistent physical demands placed on the bodies of Active Duty service members results in life-long musculoskeletal issues, particularly post-traumatic arthritis, as well as psychological disturbances from chronic pain.

It has been shown that US military personnel develop osteoarthritis of the knee at rates up to 50% higher than age matched civilian counterparts.1 A recent retrospective review of total knee arthroplasty in active duty service members under age 50 years, found that nearly 75% of the knees had experienced prior ligamentous, meniscal, or chondral injury prior to arthroplasty, compared to 9.8% observed in a high volume civilian adult reconstruction practice.2 They reported an average of 17.2 years from injury to arthroplasty in this population.3 There is a paucity of data examining the prevalence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis of other major joints, including the hip, shoulder, and ankle, in the military population, but is believed to be significant.

Chronic pain and opioid abuse are endemic in our country; the military and veteran communities are not immune from these issues. Traumatic brain injuries, post-concussive syndrome, post traumatic stress disorder, and behavioral health disorders, combined with the stigma attached to these issues, complicates the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pain in this patient group. Chronic pain due to musculoskeletal pain and combat-related polytrauma pain has been reported in up to 50% of the Veteran community and 44% among US service members after combat deployment compared to 26% in the general population.4

Extremity trauma resulting from high-energy explosives in Iraq and Afghanistan was common; 54% of evacuated wounded service members had extremity injures. More than one-quarter (26%) of all extremity war injuries involved fractures; 82% were open.5 The Military Extremity Amputation/Limb Salvage (METALS) Study found that participants with a unilateral or bilateral amputation had significantly better SMFA functional outcomes than those whose limbs had been salvaged. This is contrary to what was found in the civilian LEAP study, where there were no significant differences in outcomes at two or seven years post injury.5 Amputees were nearly three times as likely to be engaged in a vigorous sport or recreational activity. However, the percentage working/on active duty or in school was the same, as were the rates of depression.5 Future key challenges in this population after discharge from military service include: access to care, prosthetic maintenance, activities of daily living, vocational rehabilitation, and quality of life.

The burden of musculoskeletal disease on the military population is vast and spans across the service member’s lifetime. The physical nature demanded by military requirements places its Active Duty and Reserve members at risk of suffering from acute, chronic, and life-long musculoskeletal conditions. Great strides have been made in developing ways to prevent and identify these issues sooner, but much work remains to be done.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.0.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.0.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.0.2.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.0.2.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f01png

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.0.1.png

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f02png

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.0.2.png

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f03png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.0.3.png

[11] https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/medical-discharges-among-uk-service-personnel-statistics-index

[12] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11401381_Does_military_service_damage_females_An_analysis_of_medical_discharge_data_in_the_British_armed_forces

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.1.pdf

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.1.csv

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f11png

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.1.1.png

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.2.pdf

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.2.csv

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f12png

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.1.2.png

[21] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.3.pdf

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.1.3.csv

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f13png

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.1.3.png

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.1.pdf

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.1.csv

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f21png

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.2.1.png

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.2.pdf

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.2.csv

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.3.pdf

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.2.3.csv

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f22png

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.2.2.png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.1.pdf

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.1.csv

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.3.pdf

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.3.csv

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f31png

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.3.1.png

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.2.pdf

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.2.csv

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.4.pdf

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.3.4.csv

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.1.pdf

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.1.csv

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.2.pdf

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.2.csv

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f41png

[50] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.4.1.png

[51] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.3.pdf

[52] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_5f.1.4.3.csv

[53] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g5f51png

[54] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_g5f.5.1.png

[55] http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1050457.pdf

[56] https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/financial-legacy-iraq-and-afghanistan-how-wartime-spending-decisions-will-constrain