[6]

[6]

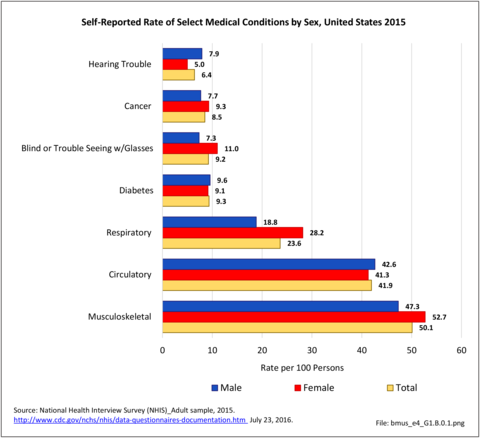

In the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2015, an annual survey of self-reported health conditions used throughout this chapter to highlight chronic health conditions of the US population, musculoskeletal medical conditions were reported by 124.1 million adults in the United States, representing one in two persons age 18 and over of the estimated 2015 population. The rate of chronic musculoskeletal conditions found in the adult population is greater than that of chronic circulatory conditions, which include coronary and heart conditions, and twice that of all chronic respiratory conditions, the next two most common health conditions. While the rate of circulatory conditions is approaching the rate of musculoskeletal conditions, the majority of circulatory conditions involve high blood pressure and high cholesterol, both of which are controlled medically and do not necessarily lead to the high levels of disability and pain found in arthritis and back pain. (Reference Tables 1.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2] and 1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

Females report higher levels of most major non-fatal health conditions than do males. The rate of musculoskeletal conditions in females was 52.7, while males reported musculoskeletal conditions at a rate of 47.3 per 100 persons. (Reference Tables 1.2.1 PDF [1] CSV [2])

Age is a factor in many major health conditions, particularly those affecting the ability to function in daily living activities. The lower prevalence of some conditions in older age groups may be due to mortality caused by the condition in earlier age groups. By age 65, circulatory problems surpass musculoskeletal conditions slightly as hypertension, high cholesterol, and heart conditions all become more common in persons who have reached the age of 75. Respiratory conditions often have lower prevalence among older individuals, while cancer, hearing problems, and dental issues all increase after age 75. The prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions rises in the middle ages of 45 to 64, and tends to level off around age 65, creating a long period of time over which the pain and disability associated with musculoskeletal diseases impacts quality of life. (Reference Table 1.2.2 PDF [7] CSV [8])

Non-Hispanic Whites have the highest prevalence of several major health disease conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions. A major exception to this rule is diabetes, a common condition; prevalence rates of diabetes are highest among non-Hispanic blacks. (Reference Table 1.2.3 PDF [11] CSV [12])

In general, residents of the Midwest region report slightly higher rates of most major health conditions while residents in the West report the lowest prevalence. Musculoskeletal conditions are reported by 54.9% of Midwest residents, and a consistent 48.8% across all other regions. The reasons why this occurs are not known, but the median age of the population is older than the West and South; however, median age is oldest in the Northeast.1 There is also a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions reported in several industries than generally found in other geographical regions. These include construction/extraction, office and administrative support, healthcare practitioners and technicians, and building and grounds cleaning/maintenance industries. (Reference Table 1.2.4 PDF [15] CSV [16])

Over the past decade, the reported prevalence of the most common health diseases has not changed. Reported prevalence in 2012 for several conditions was greater than in 2015, but additional years of data will be needed to determine if this is an actual slowing of these conditions. Circulatory related conditions increased significantly between 20112 and 2015, but this was primarily related to the increase in chronic hypertension, and the addition of chronic high cholesterol to the category. Musculoskeletal diseases continue to lead all medical conditions in prevalence. (Reference Table 1.2.5 PDF [19] CSV [20])

Three of the five most common medical conditions reported in 2012 were musculoskeletal conditions: low back pain, chronic joint pain, and arthritis. The other most commonly reported medical conditions are chronic hypertension and chronic high cholesterol. One in three to four persons over the age of 18 report having these conditions. Back and joint pain, along with arthritis, cause a much higher level of disability and affect quality of life at higher rates than do hypertension and high cholesterol. Major respiratory conditions are reported at much lower rates than circulatory and musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

Females report slightly higher levels of musculoskeletal conditions than do males, but males have higher rates of hypertension and high cholesterol. Age is a factor in increasing prevalence of all major conditions related to musculoskeletal and circulatory diseases, but the rates of hypertension and high cholesterol are much lower in young adults (18 to 44 years) and higher in older age groups (65 and over) than for musculoskeletal conditions. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4]; Table 1.3.2 PDF [24] CSV [25]; Table 1.3.3 PDF [26] CSV [27]; and Table 1.3.4 PDF [28] CSV [29])

Over the last decade, little progress has been made in reducing the prevalence of the most common respiratory, circulatory, and musculoskeletal diseases. In fact, musculoskeletal conditions and chronic hypertension, already affecting a majority of the population, have all seen a slight growth in prevalence. As mentioned earlier, there has been major progress in reducing prevalence of several fatal conditions worldwide. The time has come to focus research on non-fatal diseases, such as musculoskeletal diseases, that can cause many years of pain and disability and have been growing in prevalence. (Reference Table 1.3.5 PDF [30] CSV [31])

As previously noted, musculoskeletal conditions are one of the most debilitating nonfatal health diseases, leading to chronic pain and disability and reduced quality of life. The most common musculoskeletal conditions leading to disability are back and neck pain and arthritis and chronic joint pain.

Back pain affects most people at some point in their lives. For the lucky, this pain has a known cause and is temporary, healing with time and rest. But for many, back pain is a constant in their life. Chronic back pain is considered to be back pain lasting three months or longer. While spinal changes that are the source of back pain may be known and understood, there remains a gap in understanding why some people are affected and others are not, and what can be done to prevent or repair damage done.

In 2015, 72.3 million people age 18 and older reported they experienced chronic back pain in the previous year. This is nearly one in three adults. Of this group, more than one-third (37%) had back pain severe enough that it created radiating leg pain. Two in four (39%) also reported chronic neck pain, but 61% of the 38.9 million with neck pain had chronic neck pain alone.

Females report low back and neck pain at slightly higher rates than males, with females accounting for 54% of low back pain cases, with a rate of 30.8 per 100 persons compared to 27.4 for males. There is an even greater discrepancy in reported neck pain, with females reporting a 33% higher rate per 100 persons than males. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

Low back and neck pain are common among all ages of adults, with reported prevalence leveling as people reach middle age (45 and older). There is an actual slight dip in back pain prevalence in the oldest population, age 75 and older, but back pain remains a significant source of pain and disability throughout people’s lives. (Reference Table 1.3.2 PDF [24] CSV [25])

Low back and neck pain is reported at slightly higher rates among non-Hispanic whites than found in other racial/ethnic populations. Persons of other/mixed non-Hispanic racial/ethnic groups report the lowest rates. (Reference Table 1.3.3 PDF [26] CSV [27])

Back pain is reported in similar numbers in all geographic regions, with some minor differences seen. Low back pain is reported at the highest rate (30.3/100) in the Midwest, while low back pain with radiating leg pain is slightly higher in the South (11.3/100). Neck pain is reported highest in the West (17.9/100).

About one in two persons reporting a doctor has “ever” told them they have arthritis report either chronic joint pain or low back/neck pain. It is unknown why some people with arthritis are more likely to report pain than others. More than 55.4 million report they have some type of arthritis, an overall prevalence rate of nearly one in four adults (22.4/100). Females report higher rates than males, accounting for 58% of those reporting they have arthritis. This represents a one-in-four prevalence ratio (25.4/100) compared to one-in-five (19.1/100) males. (Reference Table 1.3.1 PDF [3] CSV [4])

Age is clearly a factor in arthritis, with very low rates found in younger adults. By middle age (45-64) the prevalence rate has more than quadrupled (6.8 to 28.6/100). By the age of 65, the reported prevalence rate has again nearly doubled, to 48.1/100 adults. There is a slight increase again in the oldest population, age 75 and older. (Reference Table 1.3.2 PDF [24] CSV [25])

Persons of non-Hispanic white race/ethnic background report arthritis at a prevalence rate more than twice that of those of Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic other/mixed race/ethnicity. Non-Hispanic blacks report a rate slightly lower than non-Hispanic whites, but still nearly double that of Hispanics and non-Hispanic other/mixed race ethnicity. Understanding why these racial/ethnic differences occur could aid in understanding why some persons get arthritis while others do not, as well as why some persons with arthritis report more pain than others. (Reference Table 1.3.3 PDF [26] CSV [27])

Residents of the Midwest, with a population median age of 38.0 years, report slightly higher rates of arthritis than persons residing in other geographic regions, with residents of the West region, which has the youngest median age (35.9), reporting the lowest rate.1 (Reference Table 1.3.4 PDF [28] CSV [29])

Arthritis is associated with both chronic joint and back pain. Roughly one-half of persons reporting chronic joint pain (54%), low back pain (53%), and radiating leg pain (52%) also report they have arthritis. About one-third (32%) reporting neck pain report they have arthritis.

In recent years, chronic joint pain, defined as joint pain lasting three months or longer, has reached the prevalence level of low back pain as a common musculoskeletal condition. Chronic joint pain, was reported by 72.5 million adults age 18 and older, for a rate of 29.3 in 100 persons. Chronic joint pain and arthritis are not mutually exclusive and may be reported by the same individual. Although age is a general predictor of chronic joint pain and arthritis, with nearly one in two persons age 65 years and older reporting one or both of these conditions, the rate of reported chronic joint pain in younger persons is also of concern. In 2015, one in six persons ages 18 to 44 reported experiencing chronic joint pain in the past year, while more than one-third (37%) age 45 to 64 reported chronic joint pain. Long active lifestyles will continue to be a major cause of joint pain in the coming years. (Reference Table 1.4.1 PDF [36] CSV [37] and Table 1.4.2 PDF [38] CSV [39])

As with other musculoskeletal diseases, chronic joint pain is reported by a slightly higher rate of females than males, as well as among non-Hispanic whites, with one in three reporting chronic joint pain. Other racial/ethnic groups report a prevalence between 20 and 26 in 100 persons with chronic joint pain. Also, the Midwest geographic region reports a higher prevalence than other regions in the US. (Reference Table 1.4.3 PDF [40] CSV [41] and Table 1.4.4 PDF [42] CSV [43])

Chronic knee pain is reported by all ages older than 18 years, with nearly one in three persons age 65 and older reporting chronic knee pain, and one in four (23.9/100) among those 45 to 64 years old. Because only 1 in 10 persons age 18 to 44 reports knee pain, the overall prevalence is 19 in 100. Females report a slightly higher rate of knee pain than males do.

Shoulder pain, reported by 22.3 million of those age 18 and older in 2015, is the second most common joint site for chronic pain, with rates fairly equal for those age 45 and older. Shoulder pain is reported in fairly equal rates by males and females, with males having a slightly higher rate.

Hip pain was reported by 18.2 million people age 18 and older in 2105. Hip pain is much more common in females than in males. As with other sites of chronic joint pain, hip pain prevalence increases with age.

While multiple joints can be the source of chronic joint pain, overall, nearly one in three (29.3/100) people over the age of 18 reported chronic joint pain in 2015. The ratio jumps to nearly one in two (47/100) after the age of 65 years. However, even among younger adults age 18 to 44, about one in six (16.3/100) report chronic joint pain. (Reference Table 1.4.1 PDF [36] CSV [37] and Table 1.4.2 PDF [38] CSV [39])

Over the past eight years, a slight increase in the prevalence rate of reported chronic joint pain has been seen. This is primarily associated with knee pain, but other joints have also seen small increases.

Links:

[1] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.1.pdf

[2] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.1.csv

[3] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.1.pdf

[4] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.1.csv

[5] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b01png

[6] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.1.png

[7] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.2.pdf

[8] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.2.csv

[9] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b02png

[10] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.2.png

[11] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.3.pdf

[12] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.3.csv

[13] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b03png

[14] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.3.png

[15] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.4.pdf

[16] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.4.csv

[17] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b04png

[18] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.0.4.png

[19] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.5.pdf

[20] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.2.5.csv

[21] https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

[22] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b11png

[23] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.1.1.png

[24] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.2.pdf

[25] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.2.csv

[26] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.3.pdf

[27] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.3.csv

[28] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.4.pdf

[29] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.4.csv

[30] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.5.pdf

[31] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.3.5.csv

[32] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b21png

[33] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.1.png

[34] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b22png

[35] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.2.png

[36] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.1.pdf

[37] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.1.csv

[38] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.2.pdf

[39] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.2.csv

[40] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.3.pdf

[41] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.3.csv

[42] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.4.pdf

[43] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_T1.4.4.csv

[44] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b23png

[45] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.3.png

[46] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b24png

[47] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.4.png

[48] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/file/bmuse4g1b24tpng

[49] https://bmus.latticegroup.com/docs/bmus_e4_G1.B.2.4t.png