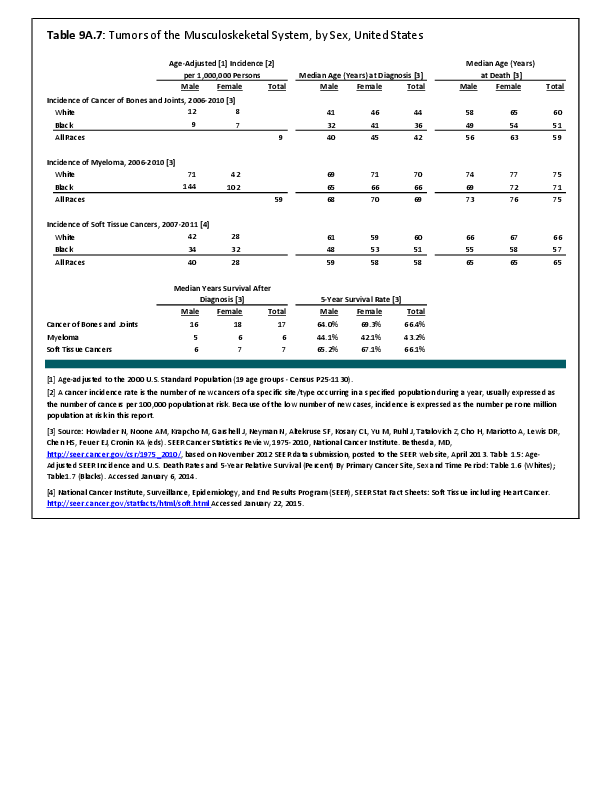

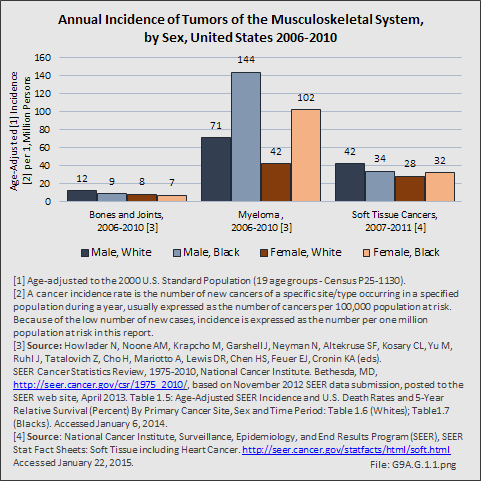

Primary sarcomas represent the least common malignancies in bone, although osteosarcoma represents the most common nonhemoapoietic primary tumor of bone. Slightly higher incidences of males have been reported for osteosarcoma (53% male versus 47% female) and Ewing sarcoma, the second most common bone and soft tissue sarcoma of young patients (55% male versus 45% female); neither is statistically significant. However, in the more common malignant lesions in bone—metastatic disease and myeloma—various studies have noted differing incidences and/or differences in outcome between the sexes.

Survival among patients with cancers continues to improve, increasing the risk for metastases. Bone is a common site of metastasis for most malignancies, and metastatic carcinoma represents the most common malignancy in bone. These typically are harbingers for poor prognosis. In addition, related skeletal events (hypercalcemia, pathologic fracture, bone pain necessitating radiation therapy, surgical intervention, spinal cord compression) lead to significant morbidity and impact on patient function, as well as shorter median survival times. Carcinomas that occur in both men and women and have a propensity for skeletal metastasis, including lung, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, have reported differing incidences between men and women of risk, location, and outcome of bone metastasis. For example, men are almost twice as likely to develop acrometastasis,1 with more than half representing metastatic lung carcinoma, reflecting the higher incidence of lung cancer among men.2

Lung cancer is a leading cancer globally, and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Men are more likely to develop lung cancer; however, women tend to be younger and less likely to be smokers, than men with lung cancer are. It has also been noted that men are more likely to have squamous cell subtype of lung carcinoma.3 Sex-based differences have not been consistently identified in the risk of metastasis or skeletal-related events (SRE), including among patients initially presenting with extensive disease,4 perhaps reflecting the shorter life expectancy among these patients.3,5 In some studies of patients with bone metastasis, women have been noted to have longer average survival than men; however, sex does not consistently remain an independent predictor of survival after accounting for younger age at diagnosis, non-smoker status, and adenocarcinoma cell type, all factors associated with improved survival and more commonly noted among women.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women; only 1% of cases of breast cancer are diagnosed in men. Men tend to be older at the time of initial diagnosis. Approximately 5% of women will present with metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis, with another 4% developing bone metastasis during follow-up. In contrast, more than 40% of men present with stage III or IV disease.6 Presentation of men at later stages of disease may reflect the impact of screening programs and greater awareness of the disease in women. For both sexes, bone is the most common location of metastasis, with approximately half of women sustaining a skeletal-related event during the course of their disease. Similar data for SREs are not available for men. Bone metastases and SREs have significant impact on survival.7 Sex has been found to be an independent risk factor for prognosis, with women having better survival. However, this may reflect the more advanced stage at the time of initial diagnosis among men because, after controlling for stage, men have been reported to have similar rates of survival as women.8 In contrast, others have suggested that the tumor biology differs between the sexes because men have been noted to have worse survival than women among those with early stage or lymph-node–negative tumors and among those with estrogen-receptor–positive tumors.6 The relative impact on survival of different tumor biology and greater awareness and screening needs to be further elucidated.

Renal cell carcinoma represents approximately 4% of new cancer diagnoses each year in the United States.9 Approximately one-third of patients will present with metastatic disease, with another one-third developing metastases later. Bone is the second most common site of metastasis, after lung; between 20% and 35% of patients will have bone metastases during the course of their disease, with 85% eventually developing an SRE.10 Although there is a higher incidence of renal cell carcinoma among men (male:female, 1.5:1), the male:female ratio increases among those with metastases at other sites (2.0) and is even higher among those with bone metastases (2.4).10 However, sex has not been identified as an independent risk factor for survival,11 including among patients with bone metastases.9

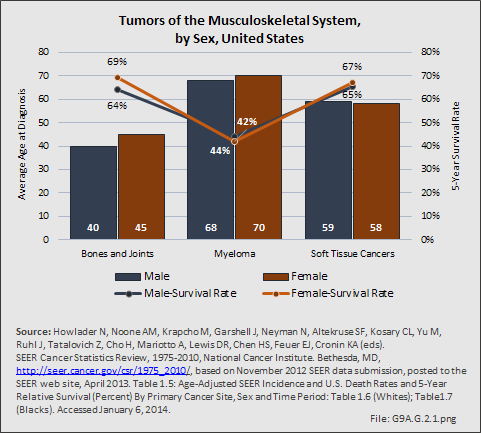

Myeloma is the most common malignancy arising in bone. Changes in bone arising from myeloma can result in osteolytic lesions, osteopenia, bone pain, and hypercalcemia. The incidence of myeloma increases with age. Men are more often diagnosed with myeloma than are women, with this sex difference initially noted at the age of 40 years. The male:female ratio increases with each decade, and is highest among those 85 years of age and older. Myeloma is also more common among Blacks for both men and women. A possible impact of female hormones on the immune system and secondary impact on the incidence of myeloma has been suggested.12 Older studies noted that males with myeloma had an increased estrogen:androgen ratio and women with myeloma had a decreased estrogen:androgen ratio, compared to controls.13 More recent studies have attempted to investigate the impact of sex hormones on the development of myeloma by correlating reproductive history with subsequent myeloma risk; results of these studies has been inconsistent, with some suggesting that increased parity is associated with increased risk of developing myeloma.12

Anthropometric characteristics14 have also been investigated in incidence of myeloma. The impact of height was found to be correlated to myeloma risk in women but not in men,15 or to have no effect on risk for either sex.16 Body mass index was reported to be related to myeloma risk in men but not women.15 However, other studies have noted that a higher BMI is related to poorer prognosis among women but not men.16 Sex-based differences in the prevalence of genetic mutations in myeloma have also been reported; immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH) translocations were found to be more common in women, and hyperdiploidy was more common in men. There were also differences in secondary genetic events with del(13q) and +1q being found more frequently in female myeloma patients.16 It has been suggested that mutations associated with poor prognosis may explain, in part, the lower overall survival noted among women with myeloma.

- 1. Malignant secondary lesions of the bones located in the hands and/or feet.

- 2. Mavrogenis AF, Mimidis G, Kokkalis ZT, et al: Acrometastases. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014 Apr;24(3):279-283. Epub 2013 Sep 8

- 3. a. b. Riihimäki M1, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Hemminki K: Causes of death in patients with extranodal cancer of unknown primary: Searching for the primary site. BMC Cancer 2014 Jun 14;14:439. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-439.

- 4. Katakami N, Kunikane H, Takeda K, et al: Prospective study on the incidence of bone metastasis (BM) and skeletal-related events (SREs) in patients with stage IIIB and IV lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014 Feb;9(2):231-238. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000051.

- 5. Cetin K, Christiansen CF, Jacobsen JB, et al. Bone metastasis, skeletal-related events, and mortality in lung cancer patients: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lung Cancer. 2014 Nov;86(2):247-254. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.08.022. Epub 2014 Sep 10.

- 6. a. b. Nahleh ZA, Srikantiah R, Safa M, et al: Male breast cancer in the veterans affairs population: A comparative analysis. Cancer 2007 Apr 15;109(8):1471-1477.

- 7. Yong C, Onukwugha E, Mullins CD: Clinical and economic burden of bone metastasis and skeletal-related events in prostate cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2014 May;26(3):274-283. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000071.

- 8. Miao H, Verkooijen HM, Chia KS, et al: Incidence and outcome of male breast cancer: An international population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2011 Nov 20;29(33):4381-4386. Epub 2011 Oct 3.

- 9. a. b. Kume H, Kakutani S, Yamada Y, et al: Prognostic factors for renal cell carincoma with bone metastasis: Who are the long-term survivors? J Urology 2011;185:1611-1624. Epub 2011 Mar 17.

- 10. a. b. Woodward E, Jagdev S, McParland L, et al: Skeletal complications and survival in renal cancer patients with bone metastases. Bone 2011 Jan;48(1):160-166. Epub 2010 Sep 18.

- 11. Fottner A, Szalantzy M, Wirthmann L, et al. Bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma: patient survival after surgical treatment. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010 Jul 3;11:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-145.

- 12. a. b. Wang S, Voutsinas J, Chang E, et al: Anthropometric, behavioral, and female reproductive factors and risk of multiple myeloma: A pooled analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:1279-1289. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0206-0.

- 13. Everaus H, Hein M, Zilmer K: Possible imbalance of the immuno-hormonal axis in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 1993 Nov;11(5-6):453-458.

- 14. Measurement of the size and proportions of the human body.

- 15. a. b. Britton JA, Khan AE, Rohrmann S, et al: Anthropometric characteristics and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Haematologica 2008 Nov;93(11):1666-1677. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13078. Epub 2008 Oct 2.

- 16. a. b. c. Teras LR, Kitahara CM, Birmann BM, et al: Body size and multiple myeloma mortality: A pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. Br J Haematol 2014 Sep;166(5):667-676. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12935. Epub 2014 May 23.

Edition:

- 2014

Download as CSV

Download as CSV